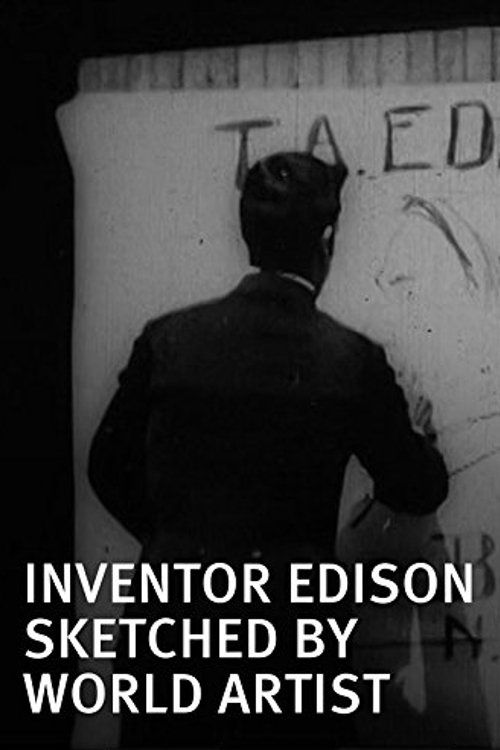

Edison Drawn by 'World' Artist

Plot

This pioneering short film captures artist J. Stuart Blackton in the act of creating a portrait of inventor Thomas Edison. The camera records Blackton as he works with chalk or charcoal on a dark surface, skillfully rendering Edison's likeness stroke by stroke. The film demonstrates the artistic process in real-time, showing how the famous inventor's face emerges from the artist's careful hand movements. As one of the earliest examples of a documentary-style recording of an artistic process, it provides viewers with a unique glimpse into both the personality of Edison and the techniques of late 19th-century portraiture. The straightforward presentation reflects the cinema of attraction aesthetic common in early film, where the mere act of capturing reality on film was itself the primary spectacle.

Director

Cast

About the Production

This film was shot using Edison's own Kinetograph camera, which was bulky and required electricity, limiting filming to the specially constructed Black Maria studio. The studio had a retractable roof to allow natural sunlight in, as electric lighting for film was not yet developed. J. Stuart Blackton, who would later become a pioneering animator, was working as a newspaper cartoonist for the New York Evening World when he was recruited for this film. The drawing was likely created on a dark background to maximize contrast for the primitive film stock of the era.

Historical Background

1896 was a pivotal year in cinema history, marking the transition from novelty to industry. The Lumière brothers had held their first public screening in Paris in December 1895, and by 1896, motion pictures were spreading rapidly across Europe and America. In the United States, Thomas Edison was fiercely protective of his motion picture patents and was building an extensive catalog of films to support his Kinetoscope parlors and emerging projection systems. The film industry was still in its infancy, with most productions being simple actuality films showing everyday scenes, performances, or demonstrations. This period saw the beginning of celebrity culture in cinema, with famous figures like Edison, Annie Oakley, and Buffalo Bill being filmed to attract audiences. The Spanish-American War in 1898 would soon demonstrate cinema's potential as a news medium, but in 1896, films were primarily entertainment curiosities shown at vaudeville theaters, world's fairs, and dedicated Kinetoscope parlors.

Why This Film Matters

This film holds considerable importance in cinema history as an early example of the documentary form and as a precursor to later art-in-process films. It represents one of the first instances of cinema recording the creative act itself, a theme that would become increasingly important in documentary filmmaking. The film also demonstrates how early cinema began to explore the concept of celebrity, using Thomas Edison's fame to attract audiences to the new medium. J. Stuart Blackton's appearance in this film is particularly significant as it represents an early intersection between established artistic disciplines and the new art form of cinema. Blackton would later bridge these worlds more explicitly by becoming a pioneer of animation, effectively using film to create art that could not exist in any other medium. The film also serves as an early example of how cinema could document and preserve cultural practices and techniques, in this case, the methods of late 19th-century portraiture.

Making Of

The making of 'Edison Drawn by 'World' Artist' took place during the explosive growth of Edison's film enterprise in 1896. James H. White, who had recently been appointed head of Edison's motion picture department, was constantly seeking novel subjects to showcase the capabilities of the Kinetograph. The collaboration with J. Stuart Blackton came about through Blackton's work as a newspaper illustrator, which had already made him somewhat known in New York media circles. The filming required careful coordination between Blackton's artistic process and the technical limitations of the camera, which could only capture about 16 frames per second and had very low light sensitivity. The Black Maria studio's unique design, with its rotating platform and retractable roof, was essential for providing adequate natural light throughout the filming session. Blackton likely had to perform the drawing multiple times to achieve the desired result, as early film was expensive and mistakes could not be edited out.

Visual Style

The cinematography in this film reflects the technical limitations and aesthetic conventions of 1896. Shot using Edison's Kinetograph camera, the film employs a static, frontal composition typical of early cinema. The camera was likely positioned at a fixed distance to capture both the artist and his work clearly within the frame. The lighting would have been natural sunlight from the Black Maria studio's retractable roof, creating the high contrast necessary for the insensitive film stock of the era. The composition carefully frames Blackton and his drawing surface, ensuring that both the artist's actions and the emerging portrait are visible to the viewer. The camera work is straightforward and functional, prioritizing clarity and documentation over artistic flourishes. The fixed position and lack of camera movement were technical necessities of the time but also reflected the theatrical influence on early film composition.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking in terms of technical innovation, this film demonstrates the sophisticated application of existing 1896 technology. The successful capture of detailed artistic work on film was notable given the limitations of contemporary film stock and cameras. The production required careful attention to lighting to ensure that the drawing process was clearly visible, showcasing the Black Maria studio's innovative design. The film also represents an early example of using cinema to document a skilled process, requiring coordination between the subject's movements and the camera's capabilities. The preservation of clear images of both the artist and his work demonstrates the improving quality of Edison's film stock and processing techniques by 1896. The film's existence also testifies to the efficiency of Edison's production system, which was capable of producing hundreds of diverse short films in a single year.

Music

As a silent film from 1896, this production had no synchronized soundtrack. During its original exhibition, it would have been accompanied by live music, typically a piano or small ensemble in vaudeville theaters or no music at all when shown on individual Kinetoscope machines. The musical accompaniment, when present, would have been improvisational or drawn from popular classical and contemporary pieces of the 1890s. Some exhibitors might have chosen music that reflected the artistic nature of the subject, possibly selecting refined or classical pieces to match the dignified presentation of portrait creation. The lack of sound was standard for the period, and audiences of the 1890s were accustomed to silent visual entertainment.

Memorable Scenes

- The complete sequence of J. Stuart Blackton methodically creating Thomas Edison's portrait, showing each stroke of the drawing instrument as the famous inventor's face gradually emerges on the drawing surface

Did You Know?

- This film represents one of the earliest instances of an artist being filmed while creating a work of art

- J. Stuart Blackton would later become known as the father of American animation, creating 'The Enchanted Drawing' in 1900

- The film was part of Edison's strategy to promote both his film technology and his own celebrity status

- Thomas Edison was one of the first celebrities to be featured in motion pictures, helping to establish the concept of film stardom

- The 'World' in the title refers to the New York Evening World newspaper where Blackton worked

- This film was likely shown on Edison's Kinetoscope peep-hole devices before being adapted for projector screening

- The running time of approximately one minute was typical for films of this period

- Black Maria studio, where this was filmed, was the world's first movie production studio

- The film demonstrates early cinema's fascination with capturing processes and skilled labor

- This was one of hundreds of short films produced by Edison Studios in 1896 alone

What Critics Said

Contemporary reception of this film is difficult to trace due to the limited film criticism of the 1890s, but it was likely well-received as part of Edison's catalog of novelty films. The Edison Company's trade publications would have promoted it as an interesting subject combining artistic skill with technological innovation. Modern film historians recognize it as an important early documentary and a significant work in the development of cinema as a medium for recording reality. Scholars point to this film as an example of early cinema's 'cinema of attractions' aesthetic, where the primary appeal was the spectacle of seeing reality captured on film rather than narrative engagement. The film is now studied in film history courses as an example of early documentary practice and as a precursor to later films about art and artists.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1896 would have been fascinated by this film for multiple reasons. The novelty of seeing an artist at work captured in motion was itself a spectacle, as was the opportunity to see a likeness of the famous inventor Thomas Edison being created before their eyes. The film appealed to both curiosity about artistic processes and the growing public fascination with celebrity figures. For viewers of the Kinetoscope, the one-minute duration was standard and the clear, focused subject would have been more engaging than some of the more chaotic street scenes also being produced. The film likely performed well in Edison's catalog because it combined educational value with entertainment, a formula that would prove successful throughout cinema's development. Modern audiences viewing the film today often express surprise at the clarity of the image and the sophisticated nature of the subject matter for such an early date.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Edison's earlier actuality films

- The tradition of artist demonstrations in art education

- Stage performances and magic shows of the 1890s

This Film Influenced

- Blackton's own animated films

- Later documentary films about artists

- Process films showing skilled craftsmanship

- Early biographical films about famous figures

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved and available through various film archives. A copy exists in the Library of Congress collection and has been included in DVD collections of early cinema. The film is in the public domain due to its age and has been digitized by several film preservation organizations. While some wear is evident in surviving prints, the essential content remains clear and viewable.