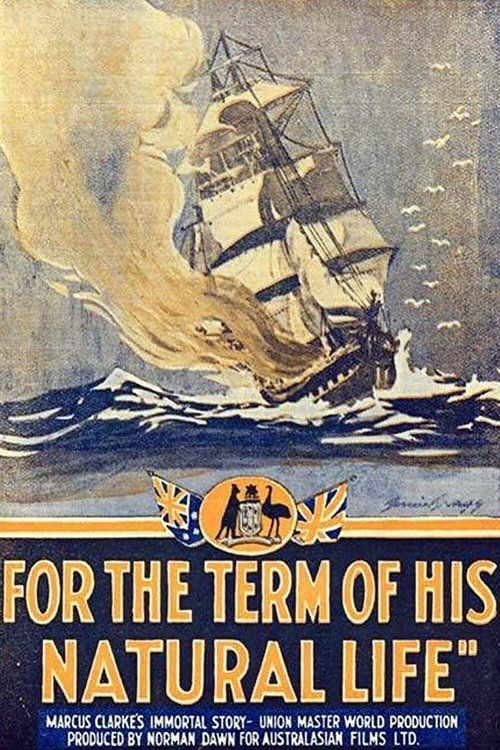

For the Term of His Natural Life

"The Greatest Australian Novel Brought to the Screen"

Plot

Based on Marcus Clarke's classic Australian novel, this silent epic tells the story of Rufus Dawes, a young man wrongfully convicted of a murder he did not commit and sentenced to transportation to the brutal penal colony of Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania). The film follows his harrowing journey through the inhumane prison system, including his time at the notorious Port Arthur penal settlement, where he endures cruel punishments and hard labor. Despite the overwhelming oppression, Dawes maintains his innocence and dignity while forming relationships with fellow prisoners, including the tragic Sylvia Vickers. The narrative builds to multiple dramatic escape attempts and a climactic revelation that could finally clear his name, all set against the unforgiving Tasmanian wilderness and the rigid hierarchy of the colonial penal system.

About the Production

The production faced numerous challenges including filming on location at the actual former penal colony of Port Arthur, which required extensive logistics and posed safety concerns. The ship sequences were filmed using a combination of full-scale vessels and miniatures in water tanks. Director Norman Dawn pioneered several special effects techniques for the film, including early matte shots to create the illusion of larger crowds and more expansive locations. The production employed over 500 extras for the prison scenes, many of whom were actual descendants of convicts.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a critical period in Australian cinema history, when the local industry was struggling to compete with Hollywood imports. The 1920s saw a dramatic decline in Australian film production, with only a handful of features being made annually. This film represented a bold attempt to create a distinctly Australian epic that could compete internationally. The choice of Marcus Clarke's novel was significant, as the book had become a symbol of Australian national identity and the convict experience that formed the foundation of modern Australian society. The film's production coincided with growing Australian cultural nationalism and a desire to tell Australian stories on screen. However, the film's release came just as the transition to sound cinema was beginning, which made its silent format seem dated to international audiences.

Why This Film Matters

For the Term of His Natural Life represents a landmark in Australian cinema history as one of the country's first epic productions and its most ambitious silent film. The film's attempt to adapt Australia's most important 19th-century novel for the screen demonstrated the cultural aspirations of the young Australian film industry. Its depiction of the convict transportation system helped cement the penal colony experience as central to Australian national identity. The film's technical achievements, particularly in special effects and location photography, pushed the boundaries of what was possible in Australian cinema at the time. Despite its commercial failure, the film has gained legendary status in Australian film history and is frequently cited as an example of what the Australian film industry could achieve during its golden age. The surviving fragments of the film are preserved as significant cultural artifacts by the Australian National Film and Sound Archive.

Making Of

The production was plagued by difficulties from the start. Director Norman Dawn, an American special effects pioneer, clashed frequently with the Australian producers over budget and creative decisions. The location filming at Port Arthur proved particularly challenging, as the historic site had fallen into disrepair and required significant restoration before filming could begin. The cast and crew had to endure harsh Tasmanian weather conditions, with temperatures often dropping below freezing during night shoots. Several scenes depicting flogging and other punishments were so realistic that some local authorities threatened to shut down production. The ship sequences required the construction of a massive water tank at the Sydney studios, where miniature ships were filmed against painted backdrops. The film's elaborate costume budget alone exceeded the entire budget of many contemporary Australian films. During post-production, Dawn experimented with early color tinting techniques, using different colors to indicate emotional states and time of day.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Arthur Higgins was groundbreaking for Australian cinema, featuring sweeping landscape shots of Tasmania that emphasized the isolation and harshness of the penal colony. Higgins used natural lighting extensively in the outdoor scenes, creating a stark contrast between the beautiful but unforgiving landscape and the brutality of human civilization within it. The prison sequences employed dramatic low-angle shots to emphasize the power dynamics between guards and prisoners. The ship scenes used innovative camera movement and miniature work to create convincing maritime sequences. The film's visual style combined documentary-like realism in the location footage with the dramatic lighting and composition typical of silent era melodramas.

Innovations

The film featured several technical innovations for Australian cinema, including Norman Dawn's pioneering matte shot techniques to create composite images and enhance the scale of scenes. The production used early camera movement devices, including a crude crane system for dramatic overhead shots. The shipwreck sequence combined full-scale practical effects with miniatures and matte paintings to create convincing maritime disaster footage. The film also experimented with color tinting, using different colored filters to indicate time of day and emotional states. The location recording at Port Arthur presented unique technical challenges, requiring the development of portable equipment that could operate in remote locations. The soundstage construction for interior prison scenes was particularly elaborate, featuring working mechanical elements for the prison doors and punishment devices.

Music

As a silent film, it was originally accompanied by a live musical score performed in theaters. The original score was composed by Sydney theater musician Hamilton Webber, who incorporated popular Australian folk melodies and classical pieces to enhance the dramatic narrative. Different theaters would have used various musical arrangements depending on their available musicians. Some screenings in major cities employed full orchestras, while smaller venues used piano accompaniment. The score featured specific musical themes for different characters and emotional moments, a practice common in silent film exhibition. No complete recording of the original score survives, though some sheet music fragments have been preserved in Australian archives.

Famous Quotes

'I am innocent, and I will prove it though it takes my natural life to do so!'

'There is no justice in this place, only the law of the strong over the weak'

'Even in hell, a man can keep his soul if he refuses to become a devil'

'This land was built on the bones of men like us'

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic flogging sequence where Rufus Dawes is brutally punished while maintaining his defiance, filmed with stark realism that shocked contemporary audiences

- The shipwreck scene where prisoners attempt escape during a storm at sea, combining practical effects and minicales to create a thrilling maritime disaster

- The climactic revelation scene where Dawes' innocence is finally proven through a dying confession, filmed with dramatic close-ups and emotional intensity

- The escape attempt through the treacherous Tasmanian wilderness, showcasing both the beauty and danger of the Australian landscape

Did You Know?

- This was the most expensive Australian film produced up to that point, costing approximately £20,000

- The film was shot on location at the actual Port Arthur penal colony, making it one of the first Australian films to use authentic historical locations

- Director Norman Dawn invented several special effects techniques specifically for this film, including early matte photography methods

- The original novel by Marcus Clarke was considered Australia's first great literary work and was required reading in Australian schools for decades

- Only incomplete versions of the film survive today, with some reels lost to deterioration

- The ship used in the filming was an actual 19th-century vessel that had been converted for use as a floating museum

- Actor George Fisher, who played Rufus Dawes, was an American actor imported from Hollywood to give the film international appeal

- The prison warden character was based on the real-life Commandant of Port Arthur, John O'Hara Booth

- The film's failure commercially nearly bankrupted Australasian Films and contributed to the decline of the Australian film industry in the 1930s

- Despite being an Australian production, the film was primarily targeted at international markets, particularly Britain and the United States

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews were mixed to positive. The Sydney Morning Herald praised the film's ambition and technical achievements, calling it 'a triumph of Australian cinematic art.' However, some critics felt the film was too melodramatic and that the American lead actor lacked authenticity. International reviews were generally more favorable, with Variety noting the film's spectacular production values and powerful storytelling. Modern critics have reassessed the film more positively, recognizing it as a significant achievement in early Australian cinema. Film historians have praised Dawn's innovative special effects and the film's ambitious scope, though they note that the surviving incomplete versions make full appreciation difficult.

What Audiences Thought

Initial Australian audience response was lukewarm, with many finding the film's brutal depiction of prison life too harsh for entertainment. The film performed better in rural areas where the convict history had stronger resonance. International audiences, particularly in Britain, responded more positively to the dramatic story and spectacular scenery. The film's commercial failure in Australia was partly attributed to audiences preferring Hollywood films and the growing anticipation of sound cinema. Over time, the film has developed a cult following among Australian film enthusiasts and historians, though its incomplete status limits its accessibility to general audiences.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Marcus Clarke's 1874 novel 'For the Term of His Natural Life'

- D.W. Griffith's epic storytelling techniques

- German Expressionist cinema's dramatic lighting

- Historical prison films such as 'The Big House' (though later)

- Australian convict folklore and literature

This Film Influenced

- Later Australian convict films including 'The Convict's Daughter' (1958)

- The 1983 TV miniseries adaptation of the same novel

- Australian New Wave films exploring national identity

- Modern Australian historical epics including 'The Proposition' (2005)

- Prison films that use historical settings to explore contemporary themes

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved but incomplete. Only approximately 70% of the original footage survives, with several key sequences lost to nitrate decomposition. The surviving elements are held by the Australian National Film and Sound Archive, which has undertaken partial restoration work. Some missing scenes exist only as still photographs and continuity scripts. The archive has created a reconstructed version using the surviving footage, intertitles, and still images to give viewers a sense of the complete narrative. The film remains on the National Film Registry as a significant work of Australian cinema heritage.