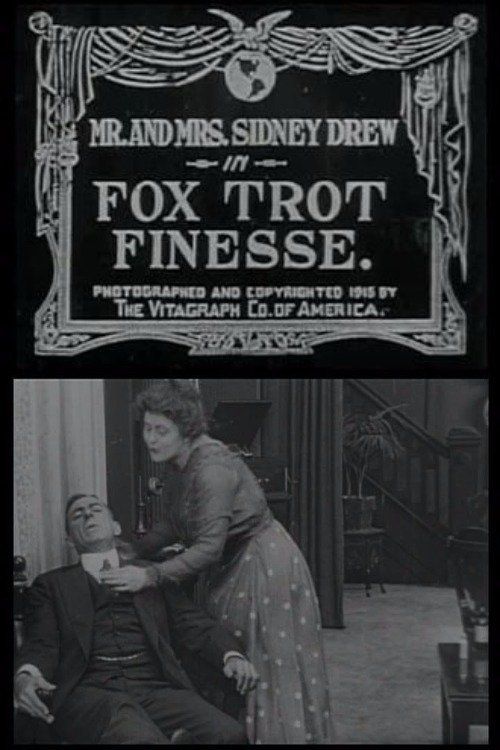

Fox Trot Finesse

Plot

In this 1915 comedy short, Ferdie (Sidney Drew) finds himself tormented by his wife's newfound obsession with the fox-trot dance craze that has swept the nation. Desperate to avoid endless nights of dancing, Ferdie cleverly fakes a serious ankle injury, complete with crutches and elaborate displays of suffering. His ruse seems successful until his wife catches him walking normally without his crutch, prompting her to write a letter inviting her stern, disapproving mother to stay with them during Ferdie's supposed recovery. Faced with the terrifying prospect of enduring his mother-in-law's constant supervision and criticism, Ferdie confesses his deception and dramatically tears up the letter, choosing dancing over maternal tyranny.

Director

About the Production

Fox Trot Finesse was produced during the height of the fox-trot dance craze that swept America in 1915. The film was part of the popular Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Drew series, which capitalized on the real-life married couple's on-screen chemistry. Sidney Drew was known for his sophisticated, upper-class comedy style that appealed to middle-class audiences of the era. The production was typical of Vitagraph's efficient studio system, completing the short film in just a few days.

Historical Background

Fox Trot Finesse was produced during a transformative period in American history and cinema. The year 1915 saw America on the cusp of entering World War I, though still maintaining neutrality. Domestically, the country was experiencing the Progressive Era's social reforms while simultaneously enjoying the cultural explosion of the Jazz Age's beginnings. The fox-trot dance craze represented a loosening of Victorian social restrictions and the emergence of more modern, liberated social customs. In cinema, 1915 was the year D.W. Griffith released The Birth of a Nation, revolutionizing film technique and demonstrating cinema's potential as an art form. Meanwhile, short comedy films like this one remained the bread and butter of most studios, providing entertainment to the millions of Americans who now attended movie theaters regularly. The film reflects the growing middle-class audience that cinema was cultivating, featuring domestic situations that resonated with their own lives and concerns.

Why This Film Matters

Fox Trot Finesse serves as a valuable time capsule of American popular culture during the mid-1910s, capturing the fox-trot dance phenomenon that swept the nation. The film reflects the changing social dynamics of the era, particularly the evolving roles and relationships between married couples. As part of the Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Drew series, it represents an early example of the domestic sitcom format that would later dominate television. The film also demonstrates how cinema served as a mirror for contemporary social trends and fads, with studios quickly producing content that capitalized on current crazes. The Drews' sophisticated comedy style, emphasizing wit and situation over slapstick, influenced the development of more refined film comedy that would later be perfected by artists like Ernst Lubitsch and Preston Sturges.

Making Of

The production of Fox Trot Finesse took advantage of the real-life marriage between Sidney Drew and Lucille McVey, whose natural chemistry translated well to the screen. The Drews had developed a signature style of domestic comedy that focused on the humorous conflicts between married couples, often with the husband trying to outsmart his wife only to be foiled in the end. The film was shot on Vitagraph's Brooklyn studio lot, where the company had built numerous standing sets for domestic interiors. The dance sequences required the cast to learn the popular fox-trot steps, which were still relatively new to the public. Sidney Drew, who was in his fifties during filming, had to convincingly portray both a reluctant dancer and someone faking an injury, requiring subtle physical comedy that was his specialty.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Fox Trot Finesse was typical of Vitagraph's studio productions of the era. Shot on black and white film stock with standard aspect ratio, the film utilized static camera positions for most scenes, with the camera positioned at eye level to capture the actors' performances. The lighting was naturalistic, using the studio's available light sources to create a realistic domestic atmosphere. The dance sequences likely required slightly more mobile camera work or careful choreography to ensure the performers remained within frame. The film employed the standard continuity editing techniques of the period, with clear shot-reverse-shot patterns during dialogue exchanges. The visual style emphasized clarity and readability, ensuring that the physical comedy and facial expressions of the actors were clearly visible to the audience.

Innovations

Fox Trot Finesse does not appear to feature any significant technical innovations for its time. The film was produced using standard filmmaking techniques and equipment of 1915. The production followed Vitagraph's established workflow for short comedy films, utilizing their studio facilities and standard crew. The film's technical aspects were competent and professional but not groundbreaking, which was typical for studio comedy shorts of the period. The main technical challenge would have been coordinating the dance sequences within the constraints of early film equipment, requiring careful choreography to ensure the performers remained properly framed and lit throughout the shots.

Music

As a silent film, Fox Trot Finesse would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its theatrical run. The theater organist or small orchestra would likely have played popular fox-trot tunes of the era, possibly including Harry Fox's original compositions or other popular dance music from 1915. The score would have been synchronized with the on-screen action, with lively, upbeat music during the dancing scenes and more subtle, comedic themes during the domestic sequences. The music would have enhanced the film's humor and helped convey the emotional tone of each scene. Some theaters may have used specific cue sheets provided by Vitagraph, while others relied on the musicians' improvisation skills to create appropriate accompaniment.

Famous Quotes

Ferdie: 'My dear, I fear my dancing days are over. This ankle... it's quite serious.'

Wife: 'But darling, everyone is fox-trotting! We simply must keep up with the times!'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening scene where Ferdie dramatically 'injures' his ankle while attempting to avoid dancing, complete with elaborate theatrical groaning and limping that fools his wife initially.

Did You Know?

- The fox-trot dance was invented in 1914 by vaudeville performer Harry Fox and became a national sensation by 1915, making this film extremely topical when released

- Sidney Drew and his wife Lucille McVey (billed as Mrs. Sidney Drew) were one of early cinema's most popular married comedy teams

- Sidney Drew was the uncle of the famous Barrymore acting family (Lionel, Ethel, and John)

- The film was part of a series of 'Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Drew' comedies produced by Vitagraph, with the couple playing married characters in various domestic situations

- Fox-trot dancing was considered somewhat scandalous by conservative audiences in 1915 due to its relatively close hold between partners

- Vitagraph was one of the major American film studios of the silent era, founded in 1897

- The film's title uses 'finesse' to suggest both dancing skill and clever deception, referring to both the wife's dancing and the husband's scheming

- Sidney Drew was known for his refined, gentlemanly comedy style that contrasted with the more slapstick comedy popular at the time

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of Fox Trot Finesse praised the film for its clever premise and the natural performances of the Drews. The Motion Picture News noted that 'Sidney Drew and his charming wife once again demonstrate their mastery of domestic comedy, with a timely subject that will surely delight audiences.' The New York Dramatic Mirror appreciated the film's 'gentle humor and avoidance of the coarse comedy that plagues so many shorts.' Modern film historians view the film as a representative example of the sophisticated comedy style that made the Drews popular, though it's generally considered a minor work within their filmography. The film is often cited in discussions of how early cinema reflected and capitalized on contemporary dance crazes and social fads.

What Audiences Thought

Fox Trot Finesse was well-received by audiences of 1915, particularly those who could relate to the fox-trot craze sweeping the nation. The film's domestic setting and relatable marital conflict resonated with middle-class moviegoers who were the primary audience for such productions. Contemporary theater reports indicated that the film generated good laughter and was particularly popular with female audiences, who enjoyed both the dancing content and the clever way the wife outsmarts her husband. The film's topical nature, capitalizing on a current fad, likely contributed to its initial success, as audiences enjoyed seeing their own cultural obsessions reflected on screen. The Drews had established a loyal following through their series of domestic comedies, and this film satisfied their fans' expectations while also appealing to new viewers interested in the fox-trot phenomenon.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Domestic stage comedies of the late 19th century

- Earlier Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Drew films

- Popular vaudeville routines about married life

- Contemporary newspaper comic strips about domestic situations

This Film Influenced

- Later Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Drew comedies

- Domestic comedy shorts of the late 1910s

- Early television sitcoms featuring married couples

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Fox Trot Finesse is considered a lost film. Like many silent era shorts, particularly those from smaller studios like Vitagraph, the original nitrate film elements have deteriorated or been destroyed over time. No complete copies of the film are known to exist in major film archives such as the Library of Congress, the Museum of Modern Art, or the UCLA Film & Television Archive. Some film historians hold out hope that a complete print may exist in private collections or in archives outside the United States, but as of now, the film is presumed lost.