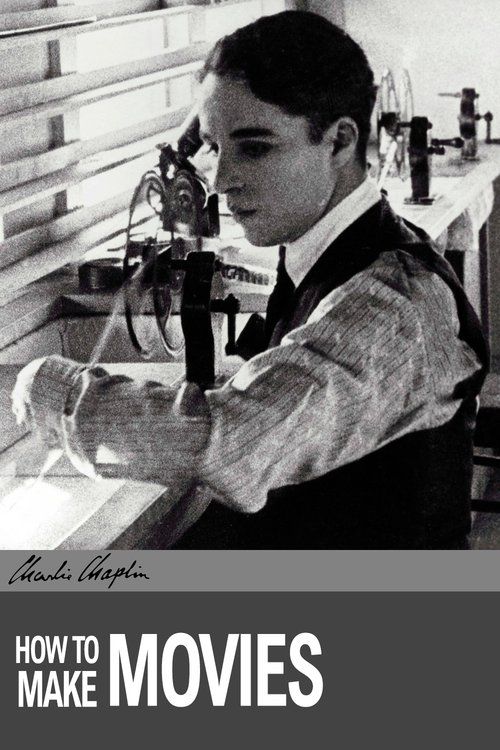

How to Make Movies

Plot

How to Make Movies is a rare behind-the-scenes documentary comedy that offers a satirical look at the film production process at Charlie Chaplin's studio. The film showcases Chaplin demonstrating various aspects of filmmaking, from script development to camera operation and editing, all while incorporating his signature comedic style. Through a series of vignettes, Chaplin parodies the technical and creative challenges of movie-making, often with himself playing multiple roles both in front of and behind the camera. The documentary serves as both an educational piece about early film techniques and a self-reflexive commentary on the burgeoning film industry. Chaplin uses the format to demystify the magic of cinema while simultaneously reinforcing his status as a master of the medium.

About the Production

This was an experimental documentary created during Chaplin's Mutual period, intended as a private record and training tool for his studio. The film was shot using Chaplin's own equipment and crew, featuring improvisational elements alongside staged demonstrations. Chaplin used this project to document his production methods for future reference and to train new crew members at his studio.

Historical Background

1918 was a pivotal year in cinema history, occurring during the final stages of World War I and at the height of the silent film era. The film industry was rapidly transitioning from short subjects to feature-length films, with Chaplin being one of the few comedians successfully making this leap. The Hollywood studio system was solidifying, and Chaplin's establishment of his own production company represented a new model of artistic independence. This period also saw significant technological advancements in film equipment and techniques, which Chaplin was documenting in this film. The war had accelerated cinema's role as a global entertainment medium, and filmmakers were becoming increasingly sophisticated in their approach to both comedy and technical innovation. Chaplin's documentary captures this transitional moment when the art of filmmaking was becoming more standardized yet still allowed for individual experimentation.

Why This Film Matters

Despite never being publicly released, How to Make Movies holds immense cultural significance as one of the earliest examples of self-reflexive filmmaking and documentary comedy. The film provides an unprecedented glimpse into the working methods of one of cinema's greatest artists, serving as an invaluable historical document of early Hollywood production techniques. Its existence demonstrates Chaplin's understanding of film as both art and industry, and his desire to preserve his methods for posterity. The film's eventual partial release in 1959 helped scholars and enthusiasts better understand Chaplin's creative process and the technical innovations of the silent era. It stands as a testament to Chaplin's role not just as a performer, but as a complete filmmaker who controlled every aspect of production. The documentary also represents an early example of meta-cinema, predating more famous self-referential works by decades.

Making Of

How to Make Movies was created during a particularly productive period in Chaplin's career when he had complete artistic control at his own studio. The film was essentially a passion project, allowing Chaplin to document and satirize the filmmaking process he had mastered. Chaplin worked closely with his regular crew, including cinematographer Roland Totheroh, to capture both authentic studio operations and staged comedic scenarios. The production involved Chaplin experimenting with self-reflexive filmmaking techniques that were ahead of their time. Much of the footage was shot between takes of his regular productions, utilizing downtime efficiently. Chaplin's perfectionist nature is evident in the careful composition of each instructional segment, which balances educational content with his trademark humor. The film also served as a testing ground for new camera techniques that Chaplin would later employ in his feature films.

Visual Style

The cinematography in How to Make Movies was handled by Chaplin's regular cameraman Roland Totheroh, utilizing the standard equipment of the era while demonstrating various techniques. The film employs multiple camera angles to show both the filming process and the results, creating a layered visual narrative. Chaplin uses the camera to simultaneously educate and entertain, with careful composition that balances technical clarity with comedic timing. The documentary showcases Chaplin's mastery of visual storytelling, even in a non-narrative format. The surviving footage reveals sophisticated use of close-ups, medium shots, and long shots to effectively demonstrate different aspects of filmmaking. The black and white photography maintains the high quality standard of Chaplin's Mutual period productions, with excellent lighting and contrast.

Innovations

How to Make Movies documents several technical innovations that Chaplin pioneered during this period, including his use of multiple cameras for coverage and his sophisticated editing techniques. The film itself was technically innovative in its approach to documentary filmmaking, blending educational content with entertainment in a way that was rare for the time. Chaplin demonstrates his methods for creating comedic effects through camera placement, timing, and editing. The documentary also showcases early special effects techniques and the practical methods used to achieve them. Chaplin's systematic approach to documenting his production methods was itself a technical achievement, creating a valuable record of silent film techniques that might otherwise have been lost.

Music

As a silent film from 1918, How to Make Movies was originally produced without a synchronized soundtrack. Like all silent films of the era, it would have been accompanied by live musical performance during any potential exhibition. When portions appeared in The Chaplin Revue in 1959, Chaplin composed new musical scores specifically for the compiled footage, including music for the segments from How to Make Movies. These later compositions reflect Chaplin's mature musical style and provide an audio context for the silent footage. The original film would have relied on intertitles for any explanatory text, combined with visual demonstrations that didn't require musical accompaniment to be understood.

Famous Quotes

Making movies is like making magic - you show people something impossible, but you have to do it perfectly

The camera is your audience, but it's also your partner in comedy

Every frame must have a purpose, every movement a meaning

Memorable Scenes

- Chaplin demonstrating multiple camera techniques by literally jumping between different cameras to show how coverage works

- The sequence where Chaplin attempts to teach his co-star Albert Austin how to properly 'act' for the camera with disastrous comedic results

- The behind-the-scenes look at how Chaplin creates his famous physical comedy effects, showing both the setup and the final result

- The segment where Chaplin parodies studio executives by playing multiple roles in a production meeting

Did You Know?

- The film remained completely unseen by the public for over 40 years, locked away in Chaplin's personal vaults at his Beverly Hills estate

- Only portions of the original footage survive today, as Chaplin selectively edited and included segments in his 1959 compilation film 'The Chaplin Revue'

- The film was created during the same period as Chaplin's classic Mutual shorts like 'The Immigrant' and 'The Adventurer'

- Chaplin appears in multiple roles throughout the documentary, both as himself and as various fictional characters demonstrating film techniques

- The documentary features rare footage of Chaplin's studio operations, including his innovative use of multiple cameras and editing techniques

- Albert Austin, Chaplin's frequent collaborator, appears in the film demonstrating various production roles

- The project was initially conceived as a training film for new employees at Chaplin's studio

- Some historians believe the film was also intended as a tax documentation tool to record Chaplin's business expenses

- The surviving footage provides invaluable insight into early Hollywood production methods that were rarely documented

- Chaplin's decision to keep the film private may have been to protect his proprietary techniques from competitors

What Critics Said

Since How to Make Movies was never released to the public during Chaplin's lifetime, contemporary critical reception is nonexistent. However, when portions of the film appeared in The Chaplin Revue in 1959, critics and scholars praised it as a fascinating window into Chaplin's creative process. Film historians have since regarded the surviving footage as an invaluable resource for understanding early film production techniques. Modern critics have highlighted the film's innovative approach to documentary filmmaking and its ahead-of-its-time self-reflexivity. The documentary is now considered an essential piece of Chaplin's filmography, despite its limited availability, and is frequently cited in academic studies of early cinema and Chaplin's working methods.

What Audiences Thought

Due to its private nature and lack of public release, How to Make Movies had virtually no audience reception during Chaplin's lifetime. The few who have seen the surviving footage—primarily film scholars, historians, and dedicated Chaplin enthusiasts—have responded with enthusiasm and fascination. When The Chaplin Revue was released in 1959, audiences were intrigued by the behind-the-scenes glimpses of Chaplin's work, though many didn't realize they were watching footage from a separate documentary. Modern audiences who have access to the surviving fragments through film archives or special editions typically express appreciation for the rare insight into Chaplin's methods and the charming humor he brings to the technical demonstrations.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Chaplin's own experience learning film techniques

- The growing industrialization of Hollywood

- Contemporary industrial and educational films

- Stage magic and performance traditions

- Early documentary pioneers like the Lumière brothers

This Film Influenced

- The Chaplin Revue (1959)

- The Unknown Chaplin (1983)

- Various modern behind-the-scenes documentaries

- Film school educational materials on silent cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film exists only in fragmentary form, with portions preserved in the Chaplin Archive at the Cineteca di Bologna in Italy. Some footage was incorporated into The Chaplin Revue (1959) and thus preserved through that compilation. The original negatives and remaining outtakes are held in the Chaplin family archives. The film has undergone restoration by the Chaplin Association and Cineteca di Bologna, though the complete original version is considered lost. The surviving elements have been digitally preserved and are occasionally screened at film festivals and special cinema events.