Journey Into Self

"A unique film experience in human understanding."

Plot

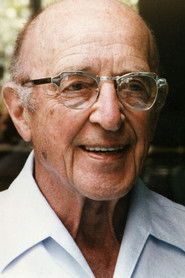

Journey Into Self is a groundbreaking documentary that chronicles a 16-hour intensive encounter group session involving eight 'well-adjusted' strangers from diverse backgrounds. Led by renowned humanistic psychologists Carl Rogers and Richard Farson, the participants—including a cashier, a theology student, a teacher, and a housewife—strip away their social masks to explore deep-seated feelings of loneliness, fear, and desire for connection. As the hours pass, the group moves from polite conversation to raw emotional honesty, culminating in powerful moments of mutual empathy and personal breakthrough. The film captures the transformative power of the 'person-centered' approach, demonstrating how a climate of freedom and acceptance can lead to profound self-discovery.

Director

Bill McGawCast

About the Production

The film was condensed from over 16 hours of continuous group interaction recorded on 16mm black-and-white film. Director Bill McGaw worked closely with the psychologists to ensure the editing preserved the emotional integrity of the session while fitting a broadcast-friendly runtime. The production was sponsored by several corporations, including Saga Food and American Airlines, which was unusual for a psychological documentary at the time.

Historical Background

Released in 1968, the film emerged during the height of the Human Potential Movement and the counterculture era in the United States. This was a period when traditional institutions were being questioned, and there was a growing societal interest in 'authenticity,' 'self-actualization,' and breaking down the rigid social barriers of the 1950s. The film reflects the shift in psychology from the 'sickness' model of psychoanalysis toward a humanistic model that viewed every individual as having an innate drive toward growth and health.

Why This Film Matters

Journey Into Self played a vital role in popularizing 'sensitivity training' and 'encounter groups' in the late 1960s and 70s. It moved therapy out of the private office and into the public eye, suggesting that emotional vulnerability was not a sign of weakness but a path to strength and community. It remains a definitive historical record of the 'Rogerian' method in practice, influencing how group dynamics are understood in both clinical and corporate settings today.

Making Of

The production faced significant technical challenges, primarily the need to film for 16 hours straight without disrupting the therapeutic process. To minimize the 'observer effect,' the crew used long lenses and tried to remain as unobtrusive as possible, though Rogers acknowledged the presence of lights and cameras in his opening remarks. The editing process was the most grueling phase, as Bill McGaw and John Hynd had to distill 16 hours of dialogue into 47 minutes without losing the narrative arc of each participant's personal 'journey.' The film was ultimately a project of the Western Behavioral Sciences Institute in La Jolla, intended to demonstrate the 'Human Potential Movement' to the public.

Visual Style

The film utilizes a 'cinéma vérité' style, characterized by handheld camera work and a lack of staged shots. The black-and-white 16mm film adds a gritty, intimate texture to the close-ups of participants' faces, capturing every flinch, tear, and subtle change in expression. The lighting is naturalistic, reflecting the actual environment of the classroom where the session was held.

Innovations

The film is a landmark in 'minimalist' documentary filmmaking, proving that a compelling feature-length narrative could be constructed from a single-room location with no script. Its success helped pave the way for the 'direct cinema' movement in the United States.

Music

The film features no traditional musical score, relying entirely on the ambient sounds of the room and the voices of the participants. This lack of music heightens the realism and ensures that the emotional impact comes solely from the human interaction rather than cinematic manipulation.

Famous Quotes

Carl Rogers: 'I feel as though really we are strangers to each other... I feel apprehensive and scared.'

Stanley Kramer: 'All of us are pretty good at carrying the secret of our own loneliness. Now these people will try to discover the secret of being together.'

Participant: 'I don't want to be a goddamn lotus blossom!'

Richard Farson: 'After your experience, I feel you've learned something that is, by gosh, irreversible.'

Memorable Scenes

- The 'Lotus Blossom' Scene: A woman expresses her frustration with being seen as a delicate object, leading to a physical and emotional confrontation that breaks the group's initial politeness.

- The Final Hug: A man who insists he 'doesn't need anybody' is finally reached by another participant, leading to a silent, tearful embrace that signifies the group's total cohesion.

- The Opening Circle: Carl Rogers' disarming admission of his own fear, which immediately levels the hierarchy between 'doctor' and 'patient.'

Did You Know?

- This was the first time an 'encounter group' session was ever captured on film for a general audience.

- The film won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature in 1969, beating out more traditional political and social documentaries.

- Stanley Kramer, the director of 'Guess Who's Coming to Dinner', was so moved by the footage that he agreed to introduce the film to help it gain mainstream distribution.

- The participants were specifically chosen because they were considered 'well-adjusted' and had no prior experience with psychotherapy.

- Carl Rogers, the 'father of person-centered therapy', begins the session by admitting his own feelings of apprehension and fear to the group.

- The film is frequently used in university psychology departments worldwide to teach the principles of group facilitation.

- Despite its Oscar win, the film remains relatively obscure in mainstream cinema history due to its specialized subject matter.

- The session took place over a single weekend, with the cameras running almost constantly to capture the natural evolution of the group's bond.

What Critics Said

At the time of its release, critics praised the film for its raw emotional power and 'voyeuristic' but respectful look at the human psyche. The New York Times and other major outlets noted its ability to make the viewer feel like a participant in the room. Modern critics and psychologists view it as a 'time capsule' of 1960s idealism, though some contemporary viewers find the black-and-white, low-fidelity aesthetic dated compared to modern high-definition documentaries.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in the late 60s were often shocked and moved by the level of public crying and physical affection (hugging) shown between strangers, which was far less common in public discourse at the time. It became a staple of the 'art house' and educational circuits, often prompting intense discussions among viewers about their own 'secret loneliness.'

Awards & Recognition

- Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature (1969)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Human Potential Movement

- Direct Cinema movement

- The works of Abraham Maslow

This Film Influenced

- The Work (2017)

- Ordinary People (1980) - thematic influence on therapy portrayal

- Various 'reality' television formats focused on group dynamics

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Academy Film Archive and is also held by the National Library of Medicine. It has been digitized for educational use.