Kurama Tengu

Plot

The 1928 installment of the Kurama Tengu series follows the adventures of the mysterious masked hero Kurama Tengu, a master swordsman who operates in the shadows of feudal Japan. Set against the backdrop of political intrigue and social unrest, the film depicts Kurama Tengu as he battles corrupt officials and protects the innocent from tyranny. The narrative builds tension through a series of confrontations with rival warriors and government agents, showcasing the hero's exceptional martial arts skills and unwavering sense of justice. The film culminates in an spectacular final sequence where Kurama Tengu, portrayed by Kanjūrō Arashi, faces overwhelming odds by wielding a sword in each hand, demonstrating his legendary prowess and cementing his status as a folk hero. This installment emphasizes themes of honor, loyalty, and the struggle between traditional values and modernizing forces in early 20th century Japan.

About the Production

The film was produced during the golden age of Japanese silent cinema and featured live musical accompaniment by benshi performers who provided narration and voice acting during screenings. The production utilized elaborate sets and costumes typical of jidaigeki (period drama) films of the era. The dual sword fighting sequence in the finale was particularly challenging to choreograph and required extensive rehearsal time. Kanjūrō Arashi performed his own stunts, which was common for leading actors in Japanese action films of this period.

Historical Background

The year 1928 was a significant period in Japanese history, occurring during the Taishō democracy era and just before the rise of militarism in the 1930s. Japan was experiencing rapid modernization and Westernization, yet there was a strong cultural movement to preserve traditional values and stories. The film industry was flourishing, with over 500 films produced annually in Japan during this period. Silent cinema was at its peak, with benshi performers becoming celebrities in their own right. The Kurama Tengu series tapped into popular nostalgia for the samurai era while reflecting contemporary concerns about justice and corruption. The film's themes of individual heroism against oppressive authority resonated with audiences during a time of social and political change. This was also the year when Japan's first sound film was released, marking the beginning of the end for the silent era that had allowed films like Kurama Tengu to flourish.

Why This Film Matters

Kurama Tengu (1928) holds immense cultural significance as one of the foundational texts of Japanese action cinema and the superhero genre. The film helped establish many tropes that would become staples of Japanese popular culture, including the masked vigilante hero with extraordinary abilities. Kanjūrō Arashi's portrayal created a template for the stoic, honorable warrior that would influence countless later characters in film, manga, and anime. The series' success demonstrated the commercial viability of long-running film franchises in Japan, paving the way for series like Zatoichi and the Lone Wolf and Cub films. The film's blend of historical setting with action elements influenced the development of the jidaigeki genre, making it more accessible to mass audiences. The character of Kurama Tengu became a cultural icon, appearing in various media including radio shows, television series, and comic books. The film's preservation and study provide valuable insights into early Japanese cinematic techniques and storytelling traditions, representing a crucial link between traditional Japanese theater and modern cinema.

Making Of

The production of Kurama Tengu (1928) took place during a transformative period in Japanese cinema, when silent films were reaching their artistic peak. Director Teppei Yamaguchi worked closely with cinematographer to create dynamic action sequences that pushed the boundaries of what was possible in silent filmmaking. The casting of Kanjūrō Arashi was a pivotal decision, as his background in traditional Japanese theater (kabuki) brought authenticity to the sword fighting sequences. The film's elaborate costumes and props were crafted by traditional artisans, ensuring historical accuracy. The production faced challenges common to the era, including the need to shoot in natural light and the limitations of early camera equipment. The famous dual sword fighting scene required weeks of rehearsal and was filmed using multiple cameras to capture the complex choreography from various angles. The benshi performers who accompanied screenings often developed their own interpretations of the story, adding another layer of creativity to each viewing experience.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Kurama Tengu (1928) represents some of the most advanced work in Japanese silent cinema. The film employed dynamic camera movements during action sequences, a relatively innovative technique for the period. The cinematographer made extensive use of low angles to emphasize the hero's imposing presence and high angles to establish sweeping views of the historical settings. The sword fighting sequences were filmed with particular care, using multiple camera setups to capture the choreography from various perspectives. The black and white photography created strong contrasts between light and shadow, enhancing the mysterious atmosphere surrounding the masked protagonist. The film also made effective use of location shooting in Kyoto, capturing authentic historical architecture and landscapes. The visual style drew inspiration from traditional Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints, particularly in the composition of static shots and the dramatic use of negative space.

Innovations

Kurama Tengu (1928) showcased several technical innovations for its time, particularly in the realm of action cinematography. The film's most notable technical achievement was the complex choreography and filming of the dual sword fighting sequence, which required innovative camera setups and editing techniques to properly capture the fast-paced action. The production team developed specialized rigging to allow for dynamic camera movements during fight scenes, creating a sense of movement and energy that was uncommon in Japanese cinema of the period. The film also employed advanced makeup and prosthetics techniques to create Kurama Tengu's distinctive mask, which needed to be both visually striking and functional for the actor during intense action sequences. The editing of action sequences used rapid cutting techniques that were ahead of their time, creating a rhythm and pace that enhanced the excitement of the sword fights. The film's special effects, while modest by modern standards, included clever use of camera tricks and stagecraft to create supernatural elements associated with the Kurama Tengu legend.

Music

As a silent film, Kurama Tengu (1928) featured no recorded soundtrack but was accompanied by live musical performances during theatrical screenings. The musical accompaniment typically consisted of traditional Japanese instruments including shamisen, taiko drums, and shakuhachi flute, sometimes combined with Western instruments like piano or violin. The benshi performer provided live narration and voice acting, delivering dialogue, sound effects, and emotional commentary throughout the screening. Famous benshi like Somei Saburo developed their own distinctive interpretations of the Kurama Tengu story, sometimes improvising additional dialogue or descriptions to enhance the drama. The musical score would vary by theater and performance, with skilled musicians creating dynamic accompaniments that heightened the tension during action sequences and emphasized emotional moments. This combination of live music and narration created a unique theatrical experience that differed with each screening, making every viewing of the film a distinct event.

Famous Quotes

Justice may be blind, but my sword sees all that is wrong with this world.

Behind this mask lies not a man, but the will of the people who cannot fight for themselves.

When corruption wears the crown of power, honor must wear the mask of rebellion.

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic final battle where Kurama Tengu, wielding two swords simultaneously, defeats an entire squad of enemy warriors in a display of extraordinary martial prowess. The scene features intricate choreography, dynamic camera work, and culminates in the hero's triumphant stance against the backdrop of a setting sun, creating an iconic image that would become synonymous with the character for decades to come.

Did You Know?

- Kurama Tengu is based on a character from Japanese folklore, a supernatural being said to live on Mount Kurama near Kyoto

- The Kurama Tengu film series was one of the most successful and long-running franchises in early Japanese cinema, with over 50 films produced between 1928 and 1959

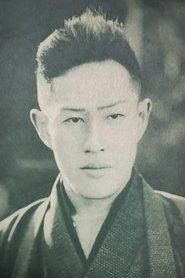

- Kanjūrō Arashi's portrayal of Kurama Tengu became the definitive version of the character, influencing all subsequent adaptations

- The film's benshi accompaniment was a crucial element of the viewing experience, with famous narrators like Somei Saburo often providing live commentary

- The dual sword fighting technique (nitojutsu) showcased in the final scene was inspired by traditional Japanese swordsmanship schools

- Many of the Kurama Tengu films were lost or destroyed during World War II, making surviving copies like this 1928 version particularly valuable

- The character's distinctive red mask and flowing robes became an iconic image in Japanese popular culture

- Director Teppei Yamaguchi was known for his dynamic action sequences and innovative camera techniques in silent films

- The film was part of a wave of jidaigeki films that romanticized Japan's feudal past during a period of rapid modernization

- The success of the Kurama Tengu series helped establish Nikkatsu Corporation as a major force in Japanese cinema

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Kurama Tengu (1928) for its exciting action sequences and Kanjūrō Arashi's charismatic performance. The film was particularly noted for its innovative camera work during the sword fighting scenes, which brought a new level of dynamism to Japanese action cinema. Critics of the era highlighted the film's successful blend of traditional Japanese aesthetics with modern cinematic techniques. The benshi accompaniment was often singled out for praise, with reviewers noting how the live narration enhanced the emotional impact of the story. Modern film historians and critics view the film as a landmark achievement in silent cinema, particularly for its influence on subsequent action films and its role in establishing the masked hero archetype in Japanese popular culture. The film is often cited in academic studies of early Japanese cinema as an example of how traditional stories were adapted for the new medium of film.

What Audiences Thought

Kurama Tengu (1928) was enormously popular with Japanese audiences upon its release, drawing large crowds to theaters across the country. The film's action sequences and heroic protagonist resonated strongly with viewers, making Kanjūrō Arashi a major star and the Kurama Tengu character a household name. Audiences particularly appreciated the film's clear moral framework and the satisfying spectacle of the hero triumphing over corruption and injustice. The benshi performances during screenings became a major draw, with famous narrators developing loyal followings among moviegoers. The film's success led to immediate demand for sequels, establishing one of Japan's first major film franchises. Contemporary audience reactions were documented in newspapers and magazines, with many viewers expressing admiration for the film's technical achievements and emotional power. The enduring popularity of the Kurama Tengu character across multiple decades testifies to the lasting impact this film had on Japanese popular culture.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Traditional Japanese kabuki theater

- Japanese folklore and mythology

- Earlier samurai films

- Western silent action films

- Jiro Osaragi's original novel

This Film Influenced

- Later Kurama Tengu films

- Zatoichi series

- Lone Wolf and Cub series

- Modern Japanese superhero films

- Samurai cinema of the 1950s and 1960s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of Kurama Tengu (1928) is uncertain but concerning. Like many Japanese films from the silent era, it is believed to be partially or completely lost. The vast majority of Japanese films from the 1920s were destroyed during World War II bombing raids, post-war occupation, or simply through neglect and the deterioration of nitrate film stock. Some fragments or still photographs from the film may exist in archives such as the National Film Center of Japan or in private collections, but a complete print has not been confirmed to survive. The film's historical significance has led to ongoing searches for surviving copies in international archives and private collections, but as of now, it remains one of the many lost treasures of early Japanese cinema.