Photograph

Plot

In this early comedy short, a photographer carefully sets up his large-format camera to take a portrait of a distinguished gentleman. The subject meticulously checks his appearance in a small hand mirror before taking his seat, while the photographer carefully poses him for the perfect shot. Just as the photographer is ready to capture the image and leans behind the camera, the curious subject stands up and walks toward the camera to inspect it more closely, ruining the composition. The photographer grows increasingly frustrated as his subject repeatedly disrupts the setup, leading to a humorous battle of wills between the two men. The film captures the timeless struggle between photographer and subject in a simple yet effective comedic scenario that would become a recurring theme in cinema.

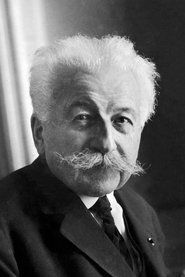

Director

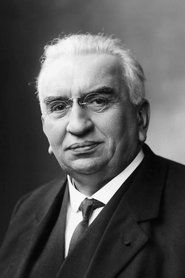

Cast

About the Production

Filmed in one continuous shot using the Cinématographe device, which served as both camera and projector. The film was shot outdoors in natural light, as artificial lighting was not yet practical for motion pictures. Auguste Lumière, who appears as the subject, was not only the director's brother but also a key partner in developing the Cinématographe technology.

Historical Background

1895 was a pivotal year in the birth of cinema, occurring during the height of the Industrial Revolution when technological innovation was transforming society. The Lumière brothers' invention of the Cinématographe came just months after other motion picture devices like Edison's Kinetoscope, but offered the crucial advantage of projection, allowing audiences to view films together. This period saw tremendous public fascination with new technologies and scientific discoveries, with exhibitions and demonstrations drawing enthusiastic crowds. France was experiencing the Belle Époque, a time of cultural flourishing and artistic innovation that provided fertile ground for the new art form of cinema. The film emerged in a world still dominated by live theater, photography, and magic lantern shows, making moving images seem like magic to contemporary audiences. The simple comedic premise of 'Photograph' reflected everyday life and situations that viewers could immediately recognize and relate to, helping bridge the gap between reality and this new technological marvel.

Why This Film Matters

'Photograph' represents one of the earliest examples of narrative comedy in cinema history, demonstrating that the new medium could do more than simply document reality. The film established the template for situational comedy that would become a cornerstone of cinematic storytelling. It showcases the Lumière brothers' understanding that cinema needed to entertain and amuse audiences, not just astonish them with technological novelty. The film's theme of the photographer's frustration with an uncooperative subject created a universal human comedy that transcended cultural and linguistic barriers, crucial for international distribution. This work helped establish cinema as a distinct art form capable of creating its own visual language and comedic timing. The film's inclusion in the very first public film screening made it part of cinema's foundational moment, influencing how early filmmakers approached the medium's potential for storytelling. Its simple yet effective premise proved that even with the extreme technical limitations of 1895 equipment, compelling human drama and comedy could be achieved.

Making Of

The filming of 'Photograph' took place in 1895 at the Lumière factory in Lyon, France, where the brothers conducted their early motion picture experiments. The scene was likely staged in the courtyard or garden of the Lumière family home, taking advantage of natural sunlight which was essential for the slow film stock of the era. Auguste Lumière, who appears as the subject, was not a professional actor but participated in many of his brother's early films out of necessity and curiosity. The filming process required the actors to remain completely still during takes, as any camera movement would have been technically challenging with the bulky Cinématographe. The entire sequence was captured in a single continuous take, as editing technology had not yet been developed. The film was processed using the Lumière brothers' own photographic development techniques, which they had perfected through their previous work in still photography.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'Photograph' demonstrates the technical capabilities and limitations of the Lumière brothers' Cinématographe. The film was shot using a single, stationary camera positioned to capture the entire interaction between the photographer and his subject. The composition carefully frames both characters and the camera equipment within the shot, establishing the scene's context clearly. Natural lighting was used, requiring careful positioning to take advantage of sunlight while avoiding harsh shadows. The film exhibits remarkable clarity for the period, thanks to the Lumière brothers' expertise in photographic chemistry. The camera work is steady and professional, reflecting Louis Lumière's background as a skilled photographer. The framing allows viewers to clearly see the characters' expressions and actions, crucial for conveying the comedy without dialogue.

Innovations

The film represents a significant technical achievement as one of the first successful demonstrations of the Cinématographe, which was superior to competing devices due to its intermittent movement mechanism and claw system. The film showcases the Lumière brothers' ability to capture smooth, natural motion at 16 frames per second, which would become the standard for silent films. The processing and developing techniques used produced images of exceptional clarity and stability for the period. The film demonstrated that the Cinématographe could effectively capture human interaction and subtle comedic timing, proving the device's suitability for narrative filmmaking. The successful projection of this film at public screenings proved the commercial viability of cinema as entertainment. The film's preservation and survival to the present day is itself a technical achievement, given the fragility of early film stock.

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic moment when the subject repeatedly stands up to inspect the camera, driving the photographer to increasing frustration, perfectly capturing the universal comedy of artistic process interrupted by curious subjects

Did You Know?

- This film was part of the very first public film screening by the Lumière brothers on December 28, 1895, at the Grand Café in Paris

- The Cinématographe camera used to film this was also capable of developing and projecting the film, making it a revolutionary all-in-one device

- Auguste Lumière, who plays the subject, was actually a talented photographer in real life and helped perfect the photographic processes used in their film work

- The film demonstrates early use of comedic timing and situational humor, proving that cinema could entertain as well as document

- At 30 seconds, this was considered a substantial length for early films, many of which were under 20 seconds

- The large-format camera shown in the film was likely a real photographic apparatus, not just a prop

- This film was one of approximately 10 films shown at the historic first public screening

- The film was shot on 35mm film with a 1.33:1 aspect ratio, which would become the standard for silent films

- Louis Lumière reportedly believed cinema was 'an invention without a future' despite creating groundbreaking films like this

- The film's simple premise of photographer vs. subject would become a recurring trope in comedy films throughout cinema history

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics and observers of the first Lumière screenings were astonished by the lifelike quality of the moving images, with 'Photograph' particularly noted for its humor and relatability. Early film enthusiasts praised the naturalistic acting and the clever use of a familiar situation to create comedy. Modern film historians recognize 'Photograph' as a significant early example of narrative construction and comedic timing in cinema. Critics today appreciate how the film demonstrates the Lumière brothers' sophisticated understanding of visual storytelling despite the medium's infancy. The film is often cited in scholarly works about early cinema as evidence that complex comedic situations could be conveyed without dialogue or intertitles. Film theorists point to this work as an early example of cinema's ability to capture and exaggerate human behavior for comedic effect.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences at the first public screening in December 1895 reportedly laughed and cheered during 'Photograph,' finding the situation both amusing and astonishingly real. Early viewers were particularly impressed by the natural movements and expressions of the performers, which contrasted with the stiff poses typical of contemporary photography. The film's humor was immediately accessible to viewers of all backgrounds, requiring no cultural knowledge or language skills to appreciate. Contemporary accounts describe audiences being delighted by the familiar frustration depicted, with many recognizing similar experiences in their own lives. The film became one of the more popular selections in the Lumière brothers' traveling exhibitions, consistently eliciting positive reactions from diverse audiences. Modern audiences viewing the film often express surprise at how effectively the comedy works despite the film's extreme brevity and the absence of sound.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage comedy traditions

- Photographic studio practices

- French theatrical farce

- Commedia dell'arte character archetypes

- Magic lantern show presentations

This Film Influenced

- Later Lumière comedies

- Early American comedies by Edison Studios

- Georges Méliès' fantasy comedies

- Charlie Chaplin's photographer-themed films

- Buster Keaton's technical comedy shorts

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved and available through various film archives and institutions, including the Lumière Institute in Lyon. The original 35mm film negative has been carefully preserved and restored, allowing modern audiences to view the film in quality close to its original presentation. Digital copies have been made from the restored elements for educational and archival purposes.