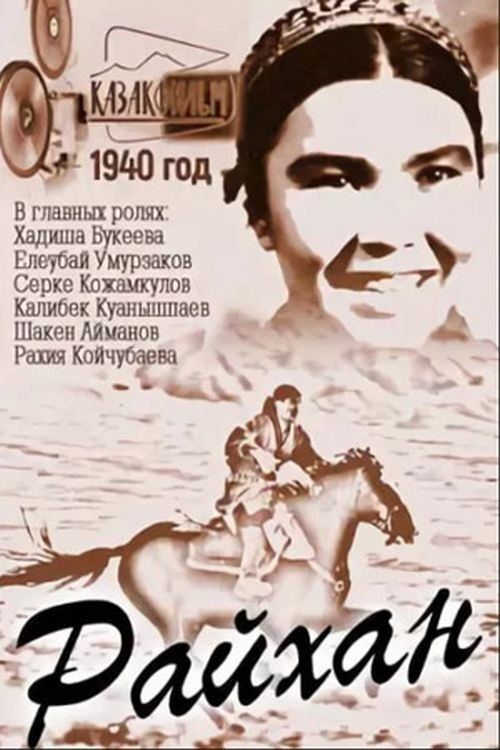

Rajchan

Plot

Rajchan tells the story of a young Kazakh woman who breaks free from traditional patriarchal constraints to embrace Soviet ideals of gender equality and modernization. Set in rural Kazakhstan during the early Soviet period, the film follows Rajchan as she challenges age-old customs that limit women's roles in society, including arranged marriages and exclusion from education. With the support of local Soviet activists and progressive community members, Rajchan learns to read and write, participates in collective farming, and becomes a leader in her community's transformation. The narrative portrays the tension between traditional Kazakh culture and Soviet modernization, with Rajchan serving as a symbol of the 'new Soviet woman.' Through her journey, the film illustrates the Soviet government's efforts to emancipate women in Central Asia while also depicting the resistance she faces from conservative elders and traditionalists.

About the Production

Filmed during a period of intense Soviet cultural transformation in Central Asia, 'Rajchan' was part of a larger state-sponsored effort to promote socialist values through cinema. The production faced challenges in finding authentic locations that could represent both traditional Kazakh life and Soviet modernization. Director Moisei Levin, who was not of Kazakh ethnicity, worked closely with Kazakh cultural consultants to ensure authenticity while maintaining the film's ideological message. The film was shot on black and white 35mm film using equipment that was relatively new to the Kazakh SSR at the time.

Historical Background

Rajchan was produced during a critical period in Soviet history when the USSR was intensifying its efforts to transform Central Asian societies. The late 1930s saw the implementation of the Great Purge, which also affected the cultural sphere, but simultaneously, the Soviet government was pushing modernization campaigns in remote republics. The film emerged from the Alma-Ata Film Studio, which had been established in 1934 as part of Stalin's policy of developing national cinemas within the Soviet framework. This period also saw the mass alphabetization campaigns, collectivization of agriculture, and the promotion of women's liberation as key Soviet policies in Central Asia. The film's release came just before the Soviet Union's entry into World War II, making it one of the last major cultural productions of the pre-war era in Kazakhstan.

Why This Film Matters

Rajchan holds a unique place in Kazakh and Soviet cinema history as one of the earliest films to explicitly address women's emancipation in a Central Asian context. It served as both entertainment and propaganda, helping to legitimize Soviet policies aimed at transforming traditional Kazakh society. The film contributed to the creation of a new cinematic language that could express both national identity and Soviet ideology. Its portrayal of a strong, independent Kazakh woman challenged traditional gender roles and provided a model for women's participation in public life. The film also helped establish a foundation for Kazakh national cinema, demonstrating that local stories could have universal appeal while serving ideological purposes. Many subsequent Kazakh films about women's issues drew inspiration from Rajchan's approach to balancing cultural authenticity with socialist messaging.

Making Of

The making of 'Rajchan' was a complex process that reflected the Soviet Union's broader efforts to modernize Central Asian cinema. Director Moisei Levin, though not Kazakh himself, spent months studying Kazakh culture and working with local advisors to ensure the film balanced authentic cultural representation with Soviet ideological requirements. The casting process was particularly challenging, as there were few professional Kazakh actors at the time, especially women. Rakhia Koychubayeva, who played Rajchan, was discovered working as a teacher and had no previous acting experience. The film crew faced logistical difficulties shooting in remote rural areas, often having to transport heavy equipment by camel or horseback. Despite these challenges, the production became a training ground for what would become Kazakhstan's first generation of professional filmmakers.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Rajchan, handled by Soviet camera operators who had been trained in Moscow, employed techniques that were innovative for Central Asian cinema of the period. The film used a combination of wide landscape shots to emphasize the vastness of the Kazakh steppe and intimate close-ups to highlight the characters' emotional journeys. The visual style contrasted the darkness and confinement of traditional settings with the brightness and openness of Soviet modernization. Notable sequences included a montage of Rajchan learning to read, intercut with scenes of collective farm work, creating a visual parallel between personal and social transformation. The black and white photography made effective use of natural light, particularly in outdoor scenes that showcased the distinctive beauty of the Kazakh landscape.

Innovations

Rajchan represented several technical milestones for the burgeoning Kazakh film industry. The production was among the first in Kazakhstan to use synchronous sound recording for dialogue, though some scenes still employed post-synchronization due to technical limitations. The film's editing techniques, particularly in the montage sequences showing social transformation, were considered sophisticated for the regional cinema of the time. The production team developed innovative methods for recording sound in outdoor locations, which was challenging due to wind conditions on the steppe. The film also experimented with special effects to show the passage of time and social progress, using techniques that were relatively new to Soviet cinema outside of Moscow and Leningrad.

Music

The musical score for Rajchan was composed by Kazakh musician Yevgeny Brusilovsky, who was instrumental in developing modern Kazakh classical music. The soundtrack skillfully blended traditional Kazakh folk melodies with Soviet orchestral arrangements, creating a musical bridge between old and new. The film featured several traditional Kazakh songs performed by the characters, which were carefully selected to represent authentic cultural elements while supporting the narrative's themes. The score used traditional Kazakh instruments like the dombra alongside Western orchestral instruments, symbolizing the cultural synthesis promoted by the Soviet project. The music was recorded using techniques that were advanced for the time in Kazakhstan, though the quality was limited by the technical resources available at the Alma-Ata studio.

Famous Quotes

A woman who cannot read is like a bird with broken wings - she cannot soar to her true potential.

Our traditions are not chains that bind us, but roots that give us strength to grow toward the sun.

Education is the key that opens the door to freedom, not just for one woman, but for all our people.

The old ways taught us to honor our past; the new ways teach us to build our future.

When a woman stands up for her rights, she stands up for the rights of all humanity.

Memorable Scenes

- The scene where Rajchan secretly learns to read by candlelight while her family sleeps, symbolizing her private rebellion against traditional constraints

- The powerful montage sequence showing Rajchan teaching other women to read, intercut with shots of collective farm work and modern machinery

- The climactic confrontation scene where Rajchan challenges the village elders about women's participation in community decision-making

- The emotional farewell scene where Rajchan's mother reluctantly accepts her daughter's choice to pursue education and independence

- The final scene showing Rajchan leading a group of women to vote in their first Soviet election, representing their full participation in public life

Did You Know?

- This was one of the first feature films to specifically address women's emancipation in Soviet Kazakhstan

- Director Moisei Levin was a Russian filmmaker who was sent to Kazakhstan to help develop the local film industry

- Shaken Aimanov, who played a supporting role, would later become one of Kazakhstan's most celebrated directors

- The film was used as educational material in literacy campaigns for women throughout Central Asia

- Original film elements were partially damaged during World War II but were later restored in the 1960s

- The title character's name 'Rajchan' was chosen to symbolize both traditional Kazakh identity and Soviet progressiveness

- The film was banned for a brief period in 1941 due to concerns that it might offend traditional Muslim populations

- Many of the costumes were authentic traditional Kazakh garments borrowed from local families

- The film's premiere was attended by Soviet officials from Moscow who praised it as a model of socialist realism

- Several scenes had to be reshot after initial screenings because they were deemed too critical of traditional Kazakh customs

What Critics Said

Upon its release, Rajchan received generally positive reviews from Soviet critics, who praised its successful implementation of socialist realism principles and its authentic portrayal of Kazakh life. Pravda and other official Soviet newspapers commended the film for effectively demonstrating the benefits of Soviet modernization for women in Central Asia. Some critics, however, noted that the film occasionally relied too heavily on stereotypical representations of traditional Kazakh society. In the decades following its release, film historians have reevaluated Rajchan as both a product of its time and a significant artistic achievement. Modern critics appreciate the film's historical value while acknowledging its propagandistic elements. The performances, particularly Rakhia Koychubayeva's portrayal of Rajchan, have been consistently praised for their naturalism and emotional depth.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary audience reactions to Rajchan were mixed and reflected the complex social transformations occurring in Kazakhstan at the time. Urban audiences, particularly young people and women, generally responded positively to the film's progressive message and relatable characters. Rural audiences, especially in more traditional areas, sometimes found the film's criticism of Kazakh customs challenging or offensive. Despite these mixed reactions, the film was commercially successful within the Kazakh SSR and was screened extensively in mobile cinema units that traveled to remote villages. Over time, as Soviet policies became more established, the film gained wider acceptance and became a cultural touchstone for generations of Kazakh viewers. Today, it is remembered fondly by older Kazakhs as an important part of their cultural heritage.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize (third degree) for outstanding achievement in cinema (1941)

- Order of the Red Banner of Labor awarded to director Moisei Levin (1940)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet socialist realist cinema

- Earlier Soviet films about women's emancipation

- Traditional Kazakh storytelling

- Soviet propaganda films

- Vsevolod Pudovkin's narrative techniques

This Film Influenced

- Amangeldy (1939)

- The Poem of Love (1954)

- The Girl of Dzhambul (1954)

- Our Dear Doctor (1957)

- If We Are All Together (1971)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The original negatives of Rajchan were partially damaged during the evacuation of film archives during World War II, but significant portions survived. The film underwent its first major restoration in the 1960s by the Gosfilmofond of the USSR. A digital restoration was completed in 2015 by the Kazakhstan Film Archive as part of a project to preserve classic Kazakh cinema. The restored version is now considered the definitive version and has been screened at international film festivals. Some scenes from the original release remain lost, particularly certain transitional sequences, but the narrative remains complete and coherent.