Santa Claus

Plot

In this pioneering Christmas film from 1898, Santa Claus is seen descending down the chimney of a house on Christmas Eve. The film begins with two children sleeping in their beds, dreaming of Christmas morning. Santa Claus then magically appears in their room, placing gifts including a doll and a trumpet under their Christmas tree. The jolly old elf checks on the sleeping children before disappearing as mysteriously as he arrived. The film concludes with the children waking up to discover their presents, bringing the simple yet magical story to its heartwarming conclusion. This brief but enchanting scene captures the wonder and excitement of Christmas morning through early cinematic techniques.

Director

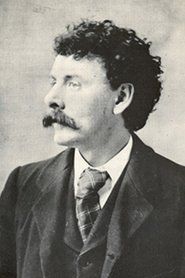

About the Production

This film was created using George Albert Smith's innovative double exposure technique to show Santa appearing magically in the children's room. The production took place in Smith's studio in Brighton, which was a hub for early British filmmaking. The film was shot on 35mm film and was one of the first to use special effects to create magical elements. The children in the film were actually Smith's own children, adding a personal touch to this Christmas production.

Historical Background

This film was created during the very dawn of cinema, just three years after the Lumière brothers' first public film screening in 1895. The late 1890s was a period of rapid experimentation with the new medium of motion pictures, with filmmakers exploring what was possible with the technology. In Britain, Brighton had emerged as an unlikely center of early filmmaking innovation, largely due to pioneers like Smith. The Victorian era was drawing to a close, and Christmas traditions were becoming increasingly commercialized and standardized, including the modern image of Santa Claus. This film captured both the technological optimism of the age and the growing cultural importance of Christmas as a major holiday.

Why This Film Matters

This film holds immense cultural significance as potentially the first cinematic representation of Santa Claus, establishing visual tropes that would influence Christmas films for over a century. It represents one of the earliest examples of holiday-themed cinema, predating the entire genre of Christmas movies. The film's magical approach to Santa's appearance set a precedent for how supernatural elements would be portrayed in cinema. It also demonstrates how quickly filmmakers recognized the commercial and emotional appeal of Christmas themes. The film helped establish Santa Claus as a cinematic character and contributed to the visual codification of Christmas mythology in popular culture.

Making Of

George Albert Smith created this film in his Brighton studio, which he had converted from a former pump house. The production involved careful planning to achieve the magical appearance of Santa Claus through double exposure techniques. Smith would first film the empty room with the sleeping children, then rewind the film and shoot Santa Claus appearing in the same frame. The children, who were Smith's own offspring, had to remain perfectly still during both takes to maintain the illusion. The set was decorated with a real Christmas tree and actual presents, adding authenticity to the scene. Smith's wife Laura Bayley, who appears in the film, was also involved in the production process, helping with costumes and props.

Visual Style

The cinematography by George Albert Smith was revolutionary for its time, employing sophisticated techniques including double exposure to create the magical appearance of Santa Claus. The film uses a static camera positioned to capture the entire room, typical of early cinema but effective for this simple narrative. The lighting was carefully managed to ensure the visibility of the subjects while maintaining the nighttime atmosphere. Smith's background in magic lantern shows influenced his approach to visual storytelling and special effects. The composition frames the sleeping children and Christmas tree to maximize the emotional impact of Santa's arrival.

Innovations

This film was groundbreaking for its use of double exposure to create the illusion of Santa Claus appearing magically in the children's room. Smith's technique involved carefully exposing the same piece of film twice, first with the empty room and sleeping children, then with Santa Claus in the frame. This was technically demanding for 1898 and required precise planning and execution. The film also demonstrated early understanding of continuity editing and narrative structure. Smith's innovative approach to special effects would influence many subsequent filmmakers and helped establish techniques that would become standard in cinema.

Music

As a silent film from 1898, there was no original soundtrack or score. When exhibited, the film would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small orchestra in music halls. The musical accompaniment would have been improvised or selected from popular Christmas carols and classical pieces appropriate to the mood. Some exhibitors might have used sound effects like bells or chimes to enhance Santa's magical appearance. The lack of synchronized sound was standard for the era, and visual storytelling had to carry the entire narrative weight.

Memorable Scenes

- The magical appearance of Santa Claus in the children's bedroom using double exposure technique, creating the illusion that he materializes from thin air beside the Christmas tree while the children sleep peacefully in their beds

Did You Know?

- This is believed to be the earliest known film adaptation of the Santa Claus legend

- Director George Albert Smith was a pioneer of special effects in early cinema

- The film uses a sophisticated double exposure technique for its time to make Santa appear magically

- At just 60 seconds, this was considered a substantial film length for 1898

- The film was distributed by the Warwick Trading Company, one of the major film distributors of the era

- Smith was a former hypnotist and magic lantern showman, which influenced his innovative approach to filmmaking

- This film predates the first feature-length film by nearly a decade

- The children in the film were Smith's own children, Harold and Dorothy Smith

- The film was part of Smith's series of fantasy films that explored magical and supernatural themes

- It was one of the first films to use parallel action, cutting between the children sleeping and Santa's arrival

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews from 1898 are scarce, but trade publications of the time noted the film's technical innovation and charming subject matter. The film was praised for its clever use of double exposure to create magical effects. Modern film historians and critics regard it as a landmark work in early cinema, particularly for its pioneering special effects. Critics today appreciate the film not just for its historical importance but for its enduring charm and simplicity. The British Film Institute and other preservation organizations have highlighted it as a crucial example of early British filmmaking and Christmas cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1898 were reportedly delighted and amazed by the film's magical effects, with many viewers wondering how Santa could appear so mysteriously in the children's room. The film was popular in music halls and fairground shows where early films were typically exhibited. Contemporary accounts suggest that children were particularly enchanted by the sight of Santa Claus on screen. The film's brief length made it perfect for the short attention spans of early cinema audiences. Today, film enthusiasts and historians appreciate it as a fascinating glimpse into both early cinema and Victorian Christmas traditions.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Magic lantern shows

- Victorian Christmas literature

- Thomas Edison's early films

- Georges Méliès' magical films

This Film Influenced

- The Night Before Christmas (1905)

- A Christmas Carol adaptations

- Modern Santa Claus films

- Christmas fantasy genre

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved and restored by the British Film Institute (BFI). A 35mm copy exists in the BFI National Archive and has been digitized for modern viewing. The restoration has maintained the original visual quality while ensuring the film's survival for future generations. The film is considered well-preserved for its age, with no significant damage or deterioration.