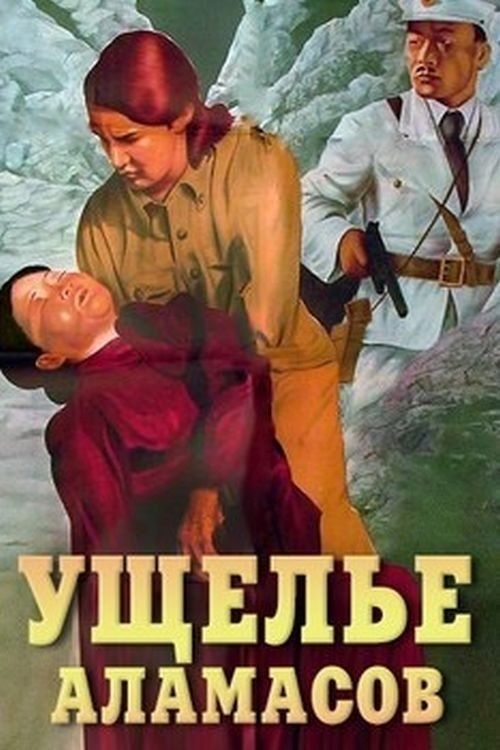

The Alamasts Gorge

"In the heart of the desert, a battle for black gold begins"

Plot

Professor Jambon leads a joint Mongolian-Soviet expedition through the harsh desert terrain toward the Alamas Mountains, where vast oil deposits are rumored to exist. The diverse team of scientists, explorers, and workers faces numerous challenges including extreme weather, difficult terrain, and internal conflicts. Unknown to the group, a saboteur has infiltrated their ranks, secretly communicating with hostile forces who seek to claim the valuable resources for themselves. As the expedition progresses, tensions rise and the saboteur's actions lead to a devastating attack that threatens the entire mission. The remaining members must fight for survival while trying to complete their scientific objectives and protect the strategic oil reserves from falling into enemy hands.

About the Production

Filmed during Stalin's Great Purge, the production faced significant political scrutiny. The film was shot on location in extreme desert conditions, requiring the crew to endure temperatures exceeding 40°C. Real Soviet geologists and oil workers were consulted to ensure authenticity of the technical aspects. The desert sequences required specialized equipment to protect the cameras from sand damage.

Historical Background

The film was produced during one of the most turbulent periods in Soviet history - 1937, the height of Stalin's Great Purge. The Soviet Union was rapidly industrializing under the Five-Year Plans, with particular emphasis on natural resource exploitation in Central Asia. The film's focus on oil exploration reflected real Soviet priorities, as the country was seeking energy independence. The saboteur plotline mirrored genuine Soviet paranoia about foreign agents and internal enemies during this period. The film also served as propaganda showcasing Soviet-Mongolian cooperation, following the 1936 Mongolian-Soviet Treaty of Friendship. International tensions were rising, with the Spanish Civil War raging and Japanese expansion in Asia threatening Soviet eastern borders, making the strategic importance of Central Asian resources particularly urgent.

Why This Film Matters

'The Alamasts Gorge' represents an important example of Soviet adventure cinema that served both entertainment and propaganda purposes. The film helped establish the template for Soviet 'production films' that glorified industrial and scientific progress. It was among the first Soviet features to realistically portray Central Asian peoples and landscapes, moving away from the exoticized stereotypes common in earlier Soviet cinema. The film's success demonstrated that Soviet audiences would respond to adventure narratives with clear ideological messages. It also influenced subsequent Soviet films about exploration and scientific achievement, establishing visual and narrative conventions that would be used for decades. The film's portrayal of Soviet-Mongolian cooperation reflected and reinforced the political reality of Soviet influence in the region.

Making Of

The production of 'The Alamasts Gorge' was fraught with challenges typical of Soviet filmmaking in the 1930s. Director Vladimir Shnejderov, known for his documentary work, insisted on authentic location shooting despite the logistical difficulties. The crew spent two months in the Karakum Desert, living in tents and dealing with sandstorms that frequently halted filming. The political climate of 1937 added another layer of tension - several crew members were under surveillance by NKVD agents who monitored the production for 'counter-revolutionary' content. The film's technical advisor, a real geologist, was arrested during production and replaced. Despite these challenges, Shnejderov managed to complete the film, though he had to make several script changes to satisfy Soviet censors who demanded stronger ideological messaging about Soviet superiority in scientific exploration.

Visual Style

The cinematography, led by Boris Volchek, was groundbreaking for its use of location photography in extreme conditions. The film employed wide-angle lenses to capture the vast desert landscapes, creating epic compositions that emphasized both the beauty and danger of the environment. Volchek used innovative techniques to protect cameras from sand damage, including custom-built housing units. The film features extensive use of natural light, particularly during the golden hour sequences that create dramatic silhouettes against the desert horizon. The attack sequence utilized multiple camera positions and rapid editing to create tension, techniques that were advanced for Soviet cinema of the period. The color-tinted sequences (in some prints) for the sunset scenes added emotional depth to key moments.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical achievements in Soviet cinema. The production developed specialized camera housings that allowed filming in sandstorms without equipment damage. The sound recording equipment was modified to function in extreme temperatures, a significant innovation for location filming. The film utilized early forms of process photography for the oil drilling sequences, combining location footage with studio effects. The desert attack sequence featured some of the most complex stunt coordination in Soviet cinema up to that point, with carefully choreographed explosions and horse stunts. The film also experimented with time-lapse photography to show the passage of days during the desert crossing, a technique rarely used in narrative films of the era.

Music

The musical score was composed by Dmitri Kabalevsky, one of Soviet Russia's most prominent composers. The soundtrack combines traditional Russian orchestral music with Mongolian folk melodies, reflecting the film's cross-cultural themes. Kabalevsky incorporated authentic Mongolian instruments, including the morin khuur (horsehead fiddle), which was recorded during location shooting. The score features leitmotifs for different characters - the Soviet explorers are accompanied by heroic brass themes, while the saboteur's music uses dissonant strings to create tension. The soundtrack was recorded using the Soviet Union's most advanced audio equipment of the time, allowing for clear dialogue recording even during the noisy desert sequences. The film's theme song became popular and was later performed by Soviet radio orchestras.

Famous Quotes

The desert does not forgive weakness, but it rewards determination with black gold beneath its sands.

Every drop of oil we find is another drop of freedom for our people.

Trust is as rare as water in this desert, but both are essential for survival.

The saboteur wears many faces, but his heart always belongs to the enemy.

Science knows no borders, but patriotism knows no compromise.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing the vast expanse of the Karakum Desert with the expedition as tiny dots against the endless sand dunes

- The sudden sandstorm that traps the expedition, filmed with actual storm conditions using special camera protection

- The discovery of the first oil gusher, shot with multiple cameras to capture the dramatic eruption

- The night attack on the camp, featuring extensive use of fire and explosions in the desert darkness

- The final confrontation with the saboteur on the edge of the gorge, with the setting sun creating dramatic silhouettes

Did You Know?

- The film was one of the first Soviet productions to feature extensive location shooting in Central Asia

- Director Vladimir Shnejderov was a renowned documentary filmmaker before transitioning to narrative features

- The oil drilling equipment shown in the film was actual working equipment borrowed from Soviet oil fields

- Several cast members were later affected by Stalin's purges, though the main stars survived

- The film's original Russian title was 'Ushchel'ye Alamasov' (Ущелье Аламасов)

- The saboteur character reflected Soviet concerns about foreign espionage during the 1930s

- Real Mongolian nomads were used as extras in several scenes

- The film was briefly banned in 1938 for 'ideological deviations' but later reinstated

- The desert attack sequence used over 200 extras and took three weeks to film

- The film's success led to increased Soviet investment in Central Asian oil exploration

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its 'heroic portrayal of Soviet scientific achievement' and 'authentic representation of working-class heroes'. Pravda specifically commended the film's 'correct ideological orientation' and 'technical excellence'. International critics were more mixed, with Variety noting the 'spectacular desert photography' but criticizing the 'heavy-handed political messaging'. Modern film historians recognize the film as an important example of 1930s Soviet cinema, particularly for its documentary-influenced visual style and its role in promoting Soviet industrial policy. Recent retrospectives of Soviet cinema have highlighted the film's technical achievements in location photography while acknowledging its function as state propaganda.

What Audiences Thought

The film was highly popular with Soviet audiences upon its release, particularly in major cities where it ran for extended engagements. Reports from Soviet cinemas indicated strong attendance, especially among young viewers who responded to the adventure elements. The film's success led to increased demand for similar adventure films with scientific themes. In Mongolia, the film was particularly well-received for its respectful portrayal of Mongolian characters and landscapes. However, audience reception varied by region - rural audiences were less enthusiastic than urban viewers. The film's popularity endured through the 1940s, with it being frequently re-released during wartime to boost morale about Soviet technological capabilities.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize, Second Class (1938)

- Best Director at the All-Union Film Festival (1938)

- Best Cinematography - Soviet Film Critics Award (1937)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- John Ford's Stagecoach (1939) - for desert cinematography techniques

- Sergei Eisenstein's October (1928) - for ideological montage

- German mountain films of Leni Riefenstahl - for landscape photography

- Hollywood adventure serials - for narrative structure

This Film Influenced

- The Great Citizen (1938) - for saboteur plot elements

- The Fall of Berlin (1949) - for scale of production

- Solaris (1972) - for scientific exploration themes

- Stalker (1979) - for journey through dangerous terrain

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The original camera negative is preserved in the Gosfilmofond archive in Moscow. Several 35mm prints exist in international archives, including the Library of Congress and the British Film Institute. The film underwent digital restoration in 2015 as part of a Soviet cinema preservation project, with damaged sections reconstructed from multiple sources. Some color-tinted sequences survive only in black and white copies. The original soundtrack was digitally remastered in 2018.