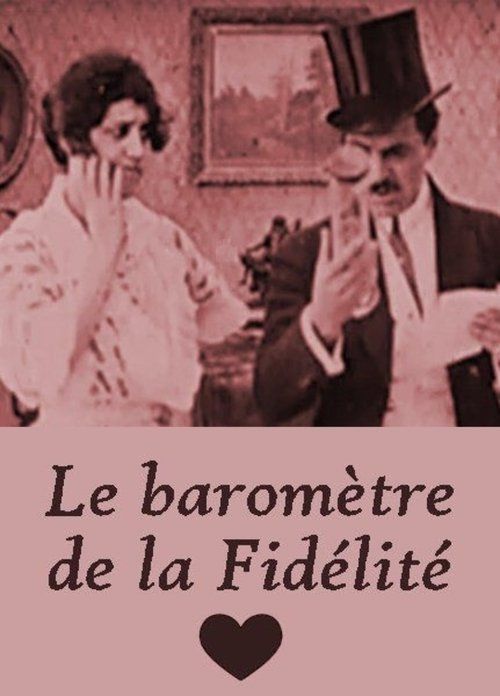

The Barometer of Fidelity

Plot

The film opens with Max Linder and his beloved girlfriend enjoying a romantic canoe ride on a serene lake, their happiness evident as they paddle together. Two years later, the scene shifts dramatically as Max discovers his girlfriend has become involved with another man, leading to a series of comedic confrontations and misunderstandings. Max attempts to win back her affection through various elaborate schemes and physical comedy routines, demonstrating his signature style of sophisticated slapstick. The narrative explores themes of trust and relationships through the lens of early 20th-century courtship customs, with Max's character navigating the complexities of romantic fidelity. The film culminates in a humorous resolution where Max's persistence and comedic timing ultimately restore the romantic equilibrium.

Director

Georges MoncaCast

About the Production

This film was produced during the golden age of French cinema when Pathé Frères dominated the global film market. The canoe scenes were likely filmed on location or in studio tanks, a common practice for water scenes in early cinema. The production utilized the standard 35mm film format of the era, with hand-cranked cameras that required precise timing for comedic effects. Max Linder, already a major star by 1909, had significant creative input in the development of his character's comedic situations and timing.

Historical Background

1909 was a pivotal year in cinema history, occurring during the transition from the 'cinema of attractions' to narrative filmmaking. The film industry was rapidly professionalizing, with major studios like Pathé Frères establishing global distribution networks. This period saw the rise of film stars, with Max Linder becoming one of the first internationally recognized actors. The year also marked the beginning of the nickelodeon boom in America, creating unprecedented demand for short films. Technologically, 1909 saw improvements in film stock quality and camera stability, allowing for more sophisticated cinematography. The film's romantic themes reflected the changing social mores of the Belle Époque era, when traditional courtship rituals were being questioned and modern dating concepts were emerging.

Why This Film Matters

'The Barometer of Fidelity' represents an important milestone in the development of romantic comedy as a film genre. Max Linder's sophisticated approach to comedy, combining visual gags with character-driven humor, influenced generations of comedians including Charlie Chaplin, who cited Linder as a major influence. The film's exploration of romantic relationships and fidelity themes established conventions that would become staples of romantic comedy for decades. As a French production distributed globally, it contributed to the international exchange of cinematic styles and techniques. The film also exemplifies the transition from stage comedy to film-specific humor, demonstrating how the new medium could create unique comedic situations impossible in live theater.

Making Of

The production of 'The Barometer of Fidelity' took place during a transformative period in cinema when films were evolving from simple novelty acts to narrative storytelling. Georges Monca, working within the Pathé studio system, collaborated closely with Max Linder, who had already established his signature character of the dapper, mustachioed gentleman facing romantic misadventures. The canoe sequence required careful planning, as early cameras were bulky and difficult to maneuver near water. The two-year time jump in the narrative was innovative for its period, demonstrating the growing sophistication of film storytelling techniques. Max Linder's background in theater influenced his precise timing and physical comedy style, which he adapted successfully to the new medium of cinema. The film was likely shot in natural light, as artificial lighting was still primitive and expensive in 1909.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'The Barometer of Fidelity' reflects the technical capabilities and aesthetic preferences of 1909. The film was likely shot using hand-cranked Pathé cameras, resulting in the variable frame rates characteristic of the era. The canoe scenes demonstrate early attempts at location shooting, with the camera positioned to capture both the romantic setting and the actors' performances. The use of medium shots was innovative for the period, allowing audiences to see Max Linder's facial expressions and subtle comedic timing. The film employed basic continuity editing to tell its story across different time periods, a technique still being refined in 1909. Lighting was primarily natural, with the outdoor scenes benefiting from daylight illumination that created a romantic atmosphere.

Innovations

The film demonstrated several technical innovations for its time, including the use of temporal jumps in narrative structure, which was relatively sophisticated for 1909. The production likely utilized the latest Pathé camera equipment, which featured improved stability and film transport mechanisms. The water scenes required special waterproofing of equipment and careful planning to avoid damage to the valuable cameras and film stock. The editing showed growing sophistication in maintaining continuity across different time periods and locations. The film's pacing and rhythm in the comedic sequences demonstrated an advanced understanding of how timing affects audience response, knowledge that Max Linder brought from his theatrical background.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Barometer of Fidelity' would have been accompanied by live music during its original theatrical run. The typical accompaniment would have been a pianist or small ensemble playing popular songs of the era, classical pieces, and improvisational music matched to the on-screen action. Romantic scenes like the canoe sequence would have featured waltzes or other popular dance music of the Belle Époque period. Comedic moments would have been highlighted with playful, staccato musical passages. The score would have been selected from the theater's existing music library, with specific pieces chosen to match the mood of each scene. Some larger theaters might have employed small orchestras for more elaborate presentations.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening canoe sequence where Max and his girlfriend paddle romantically across the lake, showcasing the idyllic beginning of their relationship before the time jump introduces conflict and sets up the comedic premise of the film.

Did You Know?

- Max Linder was one of the first international film stars, predating Charlie Chaplin's fame by several years

- Georges Monca directed over 200 films during his career, primarily working for Pathé Frères

- The film was released during the peak of Max Linder's popularity in Europe and America

- Pathé Frères was the largest film production company in the world at the time of this film's release

- The title 'The Barometer of Fidelity' reflects the Victorian-era fascination with scientific metaphors for emotional states

- Jeanne Marnac was a frequent collaborator with Max Linder during this period

- The film was likely shot in black and white, though some Pathé productions experimented with hand-tinted color sequences

- Early cinema audiences would have viewed this film with live musical accompaniment, typically piano or small orchestra

- The canoe scene represents one of the earliest examples of location shooting in romantic comedy

- Max Linder's character 'Max' was one of the first recurring comic characters in cinema history

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews in trade publications like 'The Bioscope' and 'Moving Picture World' praised Max Linder's comedic timing and the film's clever narrative structure. Critics noted the sophistication of the humor compared to the more slapstick fare common in 1909. The film was particularly appreciated for its romantic elements, which were handled with a subtlety unusual for the period. Modern film historians recognize 'The Barometer of Fidelity' as an important example of early narrative comedy, though the film itself is rarely screened today due to its age and preservation status. Retrospective analyses often highlight how Linder's character prefigured the romantic comedy protagonists of later eras.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by audiences of its time, who were growing increasingly sophisticated in their appreciation of narrative films. Max Linder had established a strong fan base across Europe and America, and his new releases were highly anticipated events. The romantic elements appealed particularly to female audiences, who were becoming an increasingly important demographic for cinema exhibitors. The canoe scene was especially popular, with audiences enjoying the combination of romance and visual spectacle. The film's success contributed to Max Linder's status as one of the highest-paid performers of his era, commanding salaries comparable to the top theatrical stars of the time.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage comedy traditions

- French theatrical farce

- Commedia dell'arte

- Early French narrative cinema

- Max Linder's previous character development

This Film Influenced

- Later Max Linder comedies

- Charlie Chaplin's romantic comedies

- Buster Keaton's relationship films

- Early American romantic shorts

- French comedy traditions of the 1910s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of 'The Barometer of Fidelity' is uncertain, as many films from this period have been lost due to the unstable nature of early nitrate film stock. Some Max Linder films from this era have survived in archives like the Cinémathèque Française and the Library of Congress, but the specific survival of this title is not definitively documented. If prints exist, they would likely be held in European film archives or private collections. The film may exist in fragmentary form or as part of compilation reels of early cinema. Restoration efforts for surviving Max Linder films have been undertaken by various archives, but individual titles from 1909 remain challenging to preserve completely.