The Big Swallow

Plot

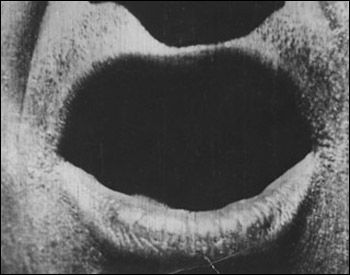

The Big Swallow depicts a man who becomes increasingly irritated at being filmed by a camera operator. As the filming continues, the man walks progressively closer to the camera until his face completely fills the frame. In a shocking and innovative moment for 1901 audiences, he opens his mouth impossibly wide and appears to swallow both the camera and the cinematographer whole. After this impossible feat, the man steps back from the camera position, chews comically, and grins triumphantly at the audience, having seemingly conquered the invasive technology of cinema itself.

Director

Cast

About the Production

The film required careful camera positioning and timing to create the illusion of the character swallowing the camera. The effect was achieved through a combination of clever staging and a jump cut, revolutionary techniques for 1901. Sam Dalton had to perform precise movements while maintaining comedic timing, and the entire sequence was likely filmed in a single take to maintain continuity.

Historical Background

The Big Swallow was created during the pioneering era of cinema (1901), when filmmakers were still discovering the language and possibilities of the new medium. The film industry was in its infancy, with most productions being short actualities or simple gag films lasting less than a minute. This period saw rapid experimentation with techniques that would become fundamental to cinema, including editing, camera movement, and special effects. The film emerged from the Brighton School of filmmaking, a group of innovative British filmmakers including Williamson, George Albert Smith, and Esmé Collins, who were pushing the boundaries of what cinema could achieve. At this time, the public was still fascinated by the basic magic of moving images, and films like The Big Swallow played with audience expectations and awareness of the filming process itself.

Why This Film Matters

The Big Swallow holds immense importance in cinema history as one of the earliest films to break the fourth wall and directly engage with the medium itself. It represents a crucial step in the evolution of film language, moving beyond simple recording of events to creating impossible scenarios through cinematic techniques. The film's playful acknowledgment of the camera's presence foreshadowed later meta-cinematic works and demonstrated early filmmakers' understanding that cinema could be self-reflexive. Its influence can be traced through countless later films that play with perspective and audience awareness. The film also captures the public's ambivalent relationship with new technology - both fascinated and threatened by the invasive capabilities of the camera. This theme remains relevant in our modern era of surveillance and social media.

Making Of

James Williamson, a former chemist turned filmmaker, created this short as part of his experimentation with cinema's possibilities. The production took place in Hove, where Williamson had established his studio. The 'swallowing' effect was ingeniously simple: Dalton would walk toward the camera, then at the precise moment his mouth opened, the camera was stopped (creating the jump cut), and Dalton would step aside while the camera was moved forward past his position. When filming resumed, Dalton would step back into frame as if emerging from inside the camera. This technique, while basic by modern standards, was revolutionary for 1901 and demonstrated Williamson's understanding of how editing could create impossible actions. The film was shot on 35mm film using a Williamson camera, and the entire sequence was choreographed to create maximum comedic impact while showcasing the new medium's capabilities.

Visual Style

The cinematography in The Big Swallow, while simple by modern standards, was innovative for its time. The film uses a static camera position for most of its duration, but the progressive movement of the actor toward the lens creates a dramatic sense of approaching perspective. The final sequence, where the camera appears to be 'swallowed,' represents one of the earliest uses of perspective manipulation in cinema. The jump cut used to create the swallowing effect was groundbreaking, demonstrating how editing could create impossible actions. The natural lighting and outdoor setting give the film an authentic feel typical of the period, while the close-up of the actor's mouth was an unusually intimate shot for 1901, pushing the boundaries of how close cameras could get to subjects.

Innovations

The Big Swallow achieved several technical milestones for its era. Most significantly, it features one of the earliest known uses of the jump cut as a special effect technique. The film also demonstrates sophisticated understanding of perspective and how camera positioning could create dramatic illusions. The precise timing required between the actor's movements and the camera stop/start operation shows remarkable technical coordination for 1901. Additionally, the film represents an early example of meta-cinema, using the camera itself as a subject and acknowledging the filming process. The seamless integration of these technical elements to create a single, coherent comedic effect was groundbreaking and influenced countless later filmmakers in their use of editing and camera tricks.

Music

As a silent film, The Big Swallow had no synchronized soundtrack. However, when originally exhibited, it would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small orchestra in music halls or theaters. The musical accompaniment would have been chosen to match the film's comedic tone, likely featuring playful, jaunty melodies that accentuated the humor. Some exhibitors might have used sound effects, such as a 'gulp' or 'chewing' noise created through percussion instruments or vocal effects to enhance the swallowing sequence. The film's short length meant it could be easily programmed with other shorts, allowing musicians to create varied musical programs throughout an exhibition.

Famous Quotes

(As a silent film, there are no recorded quotes, but the action of the character opening his mouth wide to 'swallow' the camera has become an iconic visual reference in film history)

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic sequence where Sam Dalton's character walks directly toward the camera until his face fills the frame, then opens his mouth impossibly wide to 'swallow' the camera and cinematographer - a moment that shocked and delighted 1901 audiences and remains one of cinema's earliest examples of breaking the fourth wall

Did You Know?

- This film is considered one of the earliest examples of breaking the fourth wall in cinema history

- The 'swallowing' effect was created using a jump cut - one of the earliest known uses of this editing technique

- James Williamson was a pioneering filmmaker who also created 'The Big Swallow' as a playful response to the invasive nature of early filmmaking

- The film was so popular that it inspired numerous imitations and parodies in the early 1900s

- Sam Dalton was a regular collaborator with Williamson and appeared in several of his comedy shorts

- The film demonstrates early understanding of perspective and how camera positioning could create dramatic effects

- It was one of the first films to directly acknowledge the camera's presence and the act of filming itself

- The entire film was shot outdoors using natural light, as artificial lighting was not yet common in filmmaking

- The film's title became a reference point for later films that played with similar perspective tricks

- Despite its simplicity, the film required multiple takes to perfect the timing of the 'swallowing' sequence

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics and trade publications of the early 1900s praised The Big Swallow for its ingenuity and humor. The Bioscope, a leading film trade journal, noted it as 'a most amusing trick film that demonstrates the endless possibilities of the cinematograph.' Modern film historians and critics recognize it as a landmark achievement in early cinema. Film scholar Michael Brooke has described it as 'a remarkably sophisticated piece of meta-cinema for its time,' while the British Film Institute includes it in their list of essential early British films. Critics today appreciate its pioneering use of editing and its self-aware approach to filmmaking, considering it a crucial step in the development of cinematic language.

What Audiences Thought

Early cinema audiences were reportedly delighted and amazed by The Big Swallow. The film's simple premise and surprising payoff made it extremely popular in music halls and fairground booths where early films were exhibited. Contemporary accounts suggest that audiences would laugh and cheer at the 'swallowing' sequence, with many requesting repeat viewings to understand how the effect was achieved. The film became a staple of Williamson's exhibition programs and was widely distributed internationally. Its success demonstrated that audiences were ready for more complex and self-aware films beyond simple actualities. The film's enduring popularity is evidenced by its survival and continued exhibition in film history retrospectives over 120 years later.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Georges Méliès' trick films - particularly his use of substitution splicing

- The Brighton School of filmmaking's experimental approach

- Contemporary magic shows and theatrical illusions

- Early comic strips and their visual gags

This Film Influenced

- Numerous early 1900s imitation films featuring similar perspective tricks

- Edwin S. Porter's 'The Great Train Robbery' (1903) in its use of direct camera address

- Buster Keaton's 'The Cameraman' (1928) in its exploration of filming process

- Modern meta-cinematic works like 'Adaptation' (2002) and 'Being John Malkovich' (1999)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved and available for viewing. It is held in the archives of the British Film Institute (BFI) and has been digitally restored. The BFI includes it in their collection of important early British films, and it has been made available through their online streaming service and various DVD compilations of early cinema. The film's survival is remarkable given the fragility of early film stock and the fact that many films from this period have been lost.