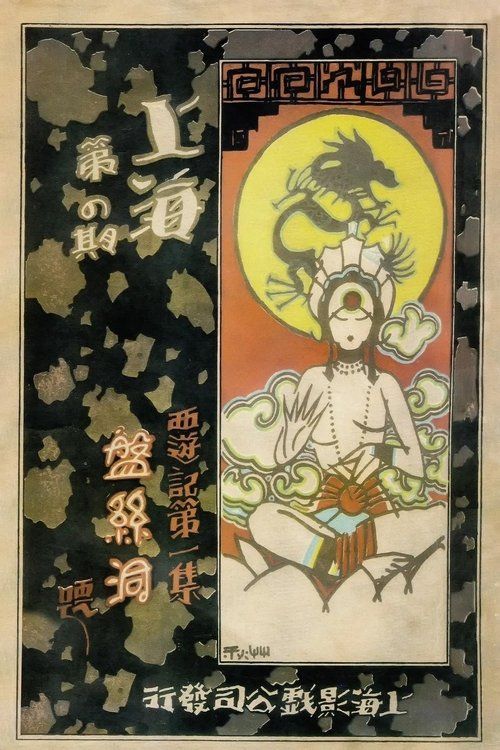

The Cave of the Silken Web

Plot

In this early Chinese fantasy adventure, the Buddhist monk Tang Xuanzang ventures alone in search of food and falls into a trap set by seven spider demons who have transformed themselves into beautiful women to seduce and capture him. The demons imprison the monk in their cave lair, intending to consume his flesh, which is said to grant immortality. When Xuanzang fails to return, his three disciples—the powerful Monkey King Sun Wukong, Pigsy Zhu Bajie, and Sandy Sha Wujing—realize their master is in danger and set out to rescue him. The Monkey King battles the spider sisters with his magical abilities, but finds himself overwhelmed by their combined powers and web-spinning attacks. Just when all seems lost, the benevolent bodhisattva Guanyin (Avalokitesvara) intervenes, helping the disciples defeat the demons and free their master. Having overcome this trial of lust and temptation, the group renounces worldly desires and continues their sacred quest to obtain Buddhist scriptures from India.

About the Production

The Cave of the Silken Web was one of the most ambitious productions of early Chinese cinema, featuring elaborate special effects for its time including transformation sequences, wire work for the Monkey King's acrobatics, and innovative techniques to create the spider demons' web effects. Director Dan Duyu, who was married to star Yin Mingzhu, pushed the technical boundaries of 1920s Chinese filmmaking. The production faced significant challenges due to the limited resources available in China's nascent film industry, requiring creative solutions to achieve the fantasy elements. The spider demon costumes were particularly elaborate, requiring multiple costume changes and intricate makeup work to transform the actresses from beautiful women to terrifying creatures.

Historical Background

The Cave of the Silken Web was produced in 1927 during a pivotal period in Chinese history known as the Warlord Era, when the country was fragmented among competing military factions. Despite the political instability, Shanghai experienced a cultural renaissance and became the center of China's burgeoning film industry. The city's international concessions provided a relatively safe haven for artistic expression, and Chinese cinema was experiencing its first golden age. This period saw the emergence of distinctly Chinese film genres and storytelling techniques, as filmmakers moved away from simply imitating Western films. The film's release came just before the Northern Expedition (1926-1928), which would eventually unify China under the Nationalist government. The choice to adapt Journey to the West was significant, as this 16th-century novel had become a cornerstone of Chinese cultural identity and was experiencing renewed popularity during this period of national reflection. The film's themes of spiritual quest and overcoming temptation resonated with audiences navigating the social upheaval of the time, while its technical achievements demonstrated China's growing cultural confidence and modernization efforts.

Why This Film Matters

The Cave of the Silken Web holds immense cultural significance as one of the earliest cinematic adaptations of Journey to the West, establishing many visual and narrative conventions that would influence countless subsequent adaptations of this beloved classic. The film helped establish the fantasy genre in Chinese cinema, demonstrating that local stories could compete with imported Western films in spectacle and entertainment value. It represented a crucial step in the development of Chinese film language, blending traditional Chinese theatrical elements with emerging cinematic techniques. The characterizations of the Monkey King and other Journey to the West figures in this film would influence how these characters were portrayed in Chinese media for decades to come. The film also reflected the growing sophistication of Chinese special effects and production design, proving that Chinese filmmakers could create elaborate fantasy worlds without relying on foreign expertise. As an adaptation of one of China's Four Great Classical Novels, the film contributed to the preservation and popularization of traditional Chinese literature and mythology in a modern medium. Its success helped pave the way for the numerous Journey to the West adaptations that would become a staple of Chinese cinema, television, and other media throughout the 20th and 21st centuries.

Making Of

The production of The Cave of the Silken Web was a remarkable achievement for 1920s Chinese cinema, requiring innovative solutions to bring the fantastical elements of Journey to the West to life. Director Dan Duyu, working with limited resources compared to Hollywood productions, developed creative techniques for the film's many special effects. The transformation sequences of the spider demons were accomplished through clever editing and makeup effects, while the Monkey King's flying scenes used early wire work techniques and careful camera angles. The elaborate spider web set was constructed using various materials including silk threads and painted glass to create ethereal lighting effects. The seven actresses playing the spider sisters underwent hours of makeup application each day, with their costumes featuring intricate designs that could be quickly modified for their transformation scenes. The film was shot on location in Shanghai and at the newly constructed studios of the Shanghai Yingxi Company, which was one of the most advanced film production facilities in China at the time. The production team worked long hours to complete the ambitious project, with many scenes requiring multiple takes due to the complexity of the special effects and the limitations of the equipment available.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Cave of the Silken Web was considered advanced for its time, employing innovative techniques to create the film's fantasy elements. The cinematographer utilized multiple exposure techniques to create the transformation effects of the spider demons, carefully layering different shots to achieve the illusion of metamorphosis. The lighting design was particularly sophisticated, using dramatic contrasts to create the mysterious atmosphere of the spider cave and the ethereal glow around the bodhisattva Guanyin. The film featured elaborate camera movements for the era, including tracking shots during the action sequences to enhance the dynamic quality of the Monkey King's battles. The cinematography also incorporated elements of traditional Chinese visual arts, with carefully composed shots that echoed classical Chinese painting in their use of space and perspective. The spider web effects were achieved through a combination of practical effects and innovative camera techniques, including the use of backlit materials to create glowing web patterns. The film's visual style blended Western cinematic techniques with distinctly Chinese aesthetic sensibilities, creating a unique visual language that would influence subsequent Chinese fantasy films.

Innovations

The Cave of the Silken Web featured several technical achievements that were groundbreaking for Chinese cinema in the 1920s. The film's special effects, particularly the transformation sequences of the spider demons, required innovative use of multiple exposure and matte painting techniques that were rarely seen in Chinese productions of the era. The wire work used to create the Monkey King's flying abilities was particularly sophisticated, involving complex rigging systems that allowed for dynamic movement while maintaining the illusion of supernatural flight. The production design included elaborate mechanical effects for the spider web sequences, using pulleys and hidden mechanisms to create the appearance of living webs that could trap characters. The makeup and prosthetic effects for the spider demon transformations were remarkably detailed, requiring multiple layers of application and careful timing to achieve the desired visual impact. The film also featured early examples of stop-motion animation for certain magical effects, demonstrating the technical ambition of the production team. These achievements were particularly impressive given the limited resources and technical infrastructure available in China's film industry at the time, representing a significant step forward in the technical capabilities of Chinese cinema.

Music

As a silent film, The Cave of the Silken Web would have been accompanied by live musical performances during its theatrical run. The typical practice in Shanghai cinemas of the 1920s involved a combination of Western orchestral instruments and traditional Chinese instruments to create an appropriate atmosphere. For a fantasy film like this, the musical accompaniment would likely have included dramatic percussion during action sequences, mysterious string arrangements for the spider cave scenes, and serene melodies for the appearance of Guanyin. The score would have been carefully synchronized with the on-screen action, with specific musical motifs for different characters and situations. While the original musical arrangements have not survived, contemporary accounts suggest that the music was an integral part of the viewing experience, enhancing the film's emotional impact and helping to bridge cultural gaps in the storytelling. Some theaters may have used traditional Chinese opera techniques for certain scenes, particularly those involving the Monkey King, whose character has deep roots in Chinese performance traditions.

Famous Quotes

Master, we must overcome all temptations on our path to enlightenment

Even the most beautiful exterior can hide a dangerous demon within

The web of desire is stronger than any spider's silk

True wisdom comes not from avoiding temptation, but from overcoming it

The path to enlightenment is fraught with trials, but with faith and friendship, we shall prevail

Memorable Scenes

- The transformation sequence where the seven beautiful women reveal their true spider demon forms, featuring groundbreaking makeup effects and multiple exposure techniques

- The Monkey King's aerial battle with the spider sisters, utilizing innovative wire work and dynamic camera movements

- The climactic appearance of Guanyin, whose divine presence is conveyed through ethereal lighting effects and serene musical accompaniment

- The elaborate spider cave set, with its intricate web design and atmospheric lighting creating a sense of danger and mystery

Did You Know?

- This is one of the earliest known film adaptations of Journey to the West, predating even the most famous adaptations by several decades

- Director Dan Duyu was married to the film's star Yin Mingzhu, making them one of early Chinese cinema's power couples

- The film was produced during the golden age of Shanghai cinema, when the city was known as the 'Hollywood of the East'

- Only fragments of this film are believed to survive today, as many Chinese films from this period were lost during the Sino-Japanese War and Cultural Revolution

- The spider demons were portrayed by seven different actresses, each requiring elaborate makeup and costume transformations

- This film was part of a series of Journey to the West adaptations made in the 1920s, though most others are now completely lost

- The special effects used to create the Monkey King's flying sequences were considered groundbreaking for Chinese cinema at the time

- Yin Mingzhu was one of China's first genuine movie stars, known as the 'Film Queen' of early Chinese cinema

- The film's production coincided with the peak of silent cinema in China, just before the transition to sound films

- The spider web effects were created using a combination of practical effects and early optical printing techniques

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception to The Cave of the Silken Web was largely positive, with reviewers praising its ambitious special effects and faithful adaptation of the beloved source material. Chinese film critics of the era particularly noted the film's technical achievements, especially considering the limitations of the Chinese film industry at the time. The performances, particularly Yin Mingzhu's portrayal of the lead spider demon, were widely acclaimed in Chinese newspapers and film magazines. Some critics expressed surprise at the sophistication of the production, noting that it rivaled foreign fantasy films in terms of visual spectacle. Modern film historians and critics have recognized the film as a pioneering work in Chinese fantasy cinema, though its incomplete preservation status has made comprehensive evaluation difficult. The film is now studied as an important example of early Chinese popular cinema and as a foundational text in the long tradition of Journey to the West adaptations. Contemporary scholars often cite it as evidence of the technical and artistic sophistication achieved by Chinese filmmakers during the silent era, challenging narratives about Chinese cinema's supposed backwardness during this period.

What Audiences Thought

The Cave of the Silken Web was reportedly popular with contemporary Chinese audiences, particularly in Shanghai where it premiered. The film's adaptation of a familiar and beloved story from Journey to the West gave it immediate recognition and appeal among moviegoers. Audiences were especially impressed by the film's spectacular special effects and the transformation sequences of the spider demons, which were discussed excitedly in theaters and social gatherings. The combination of action, fantasy elements, and moral themes resonated with Chinese audiences of the 1920s, who were navigating rapid social changes and seeking entertainment that reflected their cultural heritage. The film's success helped establish the commercial viability of fantasy films in the Chinese market and encouraged other studios to invest in similar productions. Movie theaters in Shanghai and other major cities reportedly ran the film for extended periods due to popular demand, and it was often mentioned in entertainment columns of Chinese newspapers as a must-see attraction. The film's popularity contributed to the growing fame of its stars, particularly Yin Mingzhu, who became one of the most recognizable actresses in Chinese cinema during this period.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Journey to the West novel by Wu Cheng'en

- Traditional Chinese opera and theater

- Buddhist mythology and folklore

- Chinese folk tales and legends

- Early Hollywood fantasy films

- Chinese silent cinema traditions

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent Journey to the West adaptations

- Chinese fantasy films of the 1930s-1950s

- Hong Kong martial arts fantasy films

- Modern Chinese CGI fantasy blockbusters

- Television adaptations of Journey to the West

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Cave of the Silken Web is believed to be partially lost, with only fragments of the original film surviving today. Like many Chinese films from the silent era, it suffered from the ravages of time, war, and political upheaval. Some portions of the film are preserved in the China Film Archive, while other fragments may exist in private collections or foreign archives. The incomplete preservation status makes it difficult to appreciate the film in its entirety, though the surviving footage provides valuable insight into early Chinese fantasy cinema. Film preservationists continue to search for missing reels and fragments, hoping to reconstruct more of this historically significant work. The surviving portions have been digitized and are occasionally shown at film festivals and archival screenings, allowing modern audiences to glimpse this pioneering adaptation of Journey to the West.