The Childhood of Krishna

Plot

The Childhood of Krishna (1919) depicts the playful exploits of young Krishna and his companions in Vrindavan. The film begins with Krishna's playmates being insulted by a female villager who splashes water on them, prompting them to seek revenge by stealing butter from her house. When the woman beats the children for their mischief, they turn to Krishna for help, who assists them in their retaliation. Krishna receives a gift of fruit for his assistance but selflessly gives it away to others in need. The film culminates with Krishna's most famous prank - sneaking into the home of a wealthy merchant and his wife at night, tying the man's beard to his wife's hair while they sleep. These various exploits lead to a large crowd of villagers complaining to Krishna's foster parents about his mischievous behavior, showcasing the divine child's playful nature and the challenges faced by his earthly guardians.

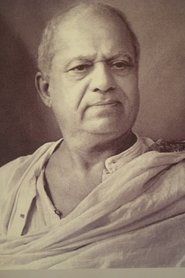

About the Production

Filmed during the early silent era of Indian cinema, this production faced significant technical challenges including limited camera equipment, natural lighting constraints, and the need to create elaborate mythological settings with minimal resources. Dadasaheb Phalke personally oversaw every aspect of production from set design to costume creation, often using local artisans and family members to keep costs manageable.

Historical Background

The Childhood of Krishna was produced during a pivotal period in Indian history and cinema. In 1919, India was under British colonial rule, with the independence movement gaining momentum following World War I. The Jallianwala Bagh massacre occurred in April 1919, sparking widespread outrage and fueling nationalist sentiments. In the realm of cinema, this was the silent era globally, with Indian filmmakers like Phalke pioneering a uniquely Indian cinematic language. The film industry was still in its infancy, with most productions being short mythological or historical stories that resonated with Indian audiences. Technology was rudimentary - cameras were hand-cranked, film stock was expensive and often imported, and there were no dedicated studios. Despite these limitations, 1919 saw increased interest in Indian-made films as audiences sought stories that reflected their own culture and values, rather than imported foreign productions.

Why This Film Matters

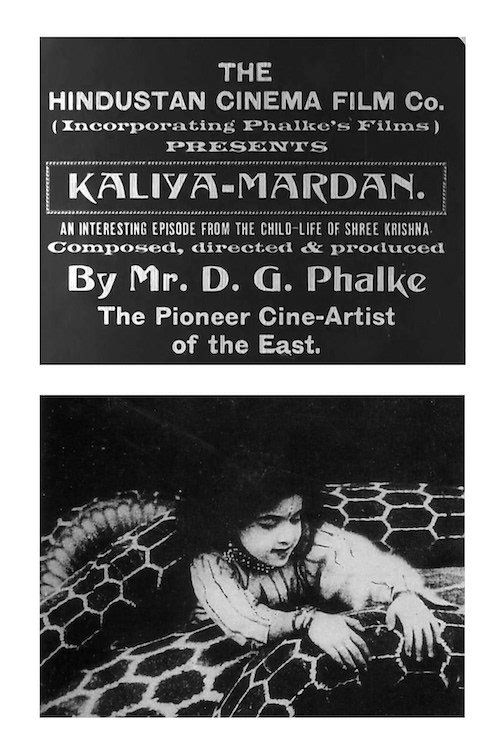

The Childhood of Krishna holds immense cultural significance as one of the earliest cinematic interpretations of Hindu mythology. It represents Dadasaheb Phalke's vision of creating an indigenous Indian cinema that could compete with foreign imports while preserving and promoting Indian cultural heritage. The film helped establish the mythological genre as a cornerstone of Indian cinema, a tradition that continues to this day in various forms. By bringing the beloved stories of Krishna's childhood to the screen, Phalke created a template for devotional cinema that would influence generations of Indian filmmakers. The film also demonstrated how cinema could serve as a medium for cultural education and religious instruction, making ancient stories accessible to modern audiences. Its success proved that Indian audiences would embrace films featuring their own cultural narratives, encouraging more filmmakers to explore Indian themes rather than imitating Western productions.

Making Of

The production of The Childhood of Krishna was typical of Dadasaheb Phalke's meticulous approach to mythological filmmaking. Phalke, who had previously worked as a photographer and lithographer, brought his artistic sensibility to every frame. The casting process was challenging, as professional actors were scarce in early Indian cinema. Many roles were filled by theater performers, amateurs, and sometimes Phalke's own family members. The sets were constructed using a combination of painted backdrops and physical props, creating a theatrical yet cinematic aesthetic. Special effects were achieved through in-camera techniques, multiple exposures, and clever editing. The film was shot outdoors whenever possible to utilize natural light, as artificial lighting equipment was primitive and expensive. Phalke was known for his hands-on approach, often working as cinematographer, editor, and sometimes even appearing in his films. The post-production process involved hand-developing the film negatives and creating intertitles, as automatic titling machines were not yet available in India.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Childhood of Krishna reflects the technical limitations and artistic innovations of early Indian cinema. Shot on hand-cranked cameras with fixed focal length lenses, the film utilized static compositions typical of the era. The cinematographer, likely Phalke himself or a close associate, had to carefully plan each shot as film was expensive and editing options were limited. Natural lighting was predominantly used, with scenes often filmed outdoors or in sets with large openings to admit daylight. The visual style incorporated elements of traditional Indian painting and theater, with careful attention to costume details and set decoration. Camera movement was minimal due to equipment constraints, but creative use of angles and composition helped create visual interest. The film employed basic special effects techniques such as multiple exposure for supernatural elements and careful editing for action sequences.

Innovations

The Childhood of Krishna showcased several technical achievements for its time and place in Indian cinema history. The film demonstrated sophisticated use of multiple exposure techniques for creating supernatural effects, particularly in scenes depicting Krishna's divine powers. The production employed elaborate set design and construction techniques that were innovative for the Indian film industry of 1919. Costume design and makeup were particularly noteworthy, with careful attention to traditional depictions of Krishna and other characters from Hindu mythology. The film utilized in-camera editing techniques and creative transitions between scenes. Special effects for the beard-tying sequence required precise timing and coordination between actors and camera work. The production also demonstrated advances in location shooting and the use of natural lighting to create atmospheric effects. These technical innovations, while primitive by modern standards, were significant achievements in the context of early Indian cinema.

Music

As a silent film, The Childhood of Krishna had no recorded soundtrack. However, during theatrical screenings, live musical accompaniment was typically provided. This often included traditional Indian instruments such as harmonium, tabla, and sitar, along with Western instruments like piano or violin depending on the theater's resources. The music was usually improvised by local musicians who would watch the film and create appropriate mood-enhancing scores. Some theaters employed narrators or commentators who would explain the on-screen action and provide additional context for the audience. The intertitles in the film were presented in regional languages, primarily Marathi or Hindi, to ensure accessibility to local audiences. The lack of synchronized sound meant that performances had to be particularly expressive and visually clear to convey emotions and narrative without dialogue.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, The Childhood of Krishna contained no spoken dialogue. The narrative was conveyed through visual storytelling and intertitles that described key plot points and character motivations.

Memorable Scenes

- The iconic butter-stealing sequence where Krishna and his friends sneak into the villager's house, showcasing the children's clever planning and execution of their plan. The scene became a template for how Krishna's mischief would be depicted in Indian cinema for decades to come.

- The nighttime prank where Krishna ties the merchant's beard to his wife's hair, demonstrating the divine child's supernatural abilities and playful nature. This scene was particularly memorable for its comedic timing and visual inventiveness within the technical constraints of 1919 cinema.

- The scene where Krishna gives away his gift of fruit to others, highlighting his divine generosity and selflessness even as a child, providing a moral lesson amidst the playful antics.

Did You Know?

- This film was directed by Dadasaheb Phalke, widely regarded as the father of Indian cinema, who made over 90 films during his career

- The film features Mandakini Phalke, Dadasaheb Phalke's daughter, in one of the early roles, showcasing the family's involvement in his productions

- During the silent era, Indian films like this one relied heavily on visual storytelling and intertitles, with live music often provided by orchestras in theaters

- The butter-stealing scenes became iconic representations of Krishna's childhood mischief and were later recreated in numerous Indian films and television shows

- Phalke's mythological films were particularly popular because they were familiar stories that resonated with Indian audiences while showcasing native culture

- The film was shot on hand-cranked cameras, requiring incredible stamina from the cinematographer who had to manually maintain consistent speed

- Many of the costumes and props were created using traditional Indian crafts techniques, with some reportedly taking weeks to complete

- The film was released just two years after the Russian Revolution and during the final stages of World War I, though India was relatively removed from direct conflict

- Phalke often imported film stock from Europe and had to time his productions carefully due to shipping disruptions during the war years

- The merchant's beard-tying scene became one of the most referenced sequences in early Indian cinema discussions

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of The Childhood of Krishna is difficult to document due to the limited film journalism infrastructure in 1919 India. However, historical accounts suggest that Phalke's mythological films were generally well-received by audiences and the few existing film critics of the era. The film was praised for its faithful representation of Krishna stories and its technical achievements within the constraints of early Indian cinema. Modern film historians and critics regard the film as an important milestone in Indian cinema history, though they note that it reflects the primitive technical capabilities of its time. The film is often studied in academic contexts for its role in establishing mythological cinema in India and for showcasing Phalke's pioneering techniques in visual storytelling.

What Audiences Thought

The Childhood of Krishna was reportedly popular with audiences of its time, particularly in regions where Krishna's stories were part of the cultural fabric. The film's depiction of familiar tales made it accessible and relatable to viewers who might have been intimidated by the new medium of cinema. Audience members often responded emotionally to the devotional elements, with some reports of viewers treating the film screenings as religious experiences. The playful scenes of Krishna's mischief, especially the butter-stealing sequences, were particularly beloved by children and adults alike. The film's success contributed to the growing acceptance of cinema as a legitimate form of entertainment and cultural expression in India, helping to overcome initial resistance from conservative elements who viewed moving pictures with suspicion.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Traditional Indian temple art and sculpture

- Classical Indian dance and theater traditions

- Bhagavata Purana and other Hindu religious texts

- Traditional Indian storytelling methods

- Early European silent films

- Marathi and Hindi folk theater

This Film Influenced

- Numerous later Indian films depicting Krishna's childhood

- The mythological film genre in Indian cinema

- Devotional cinema in India

- Later Phalke Films productions

- Regional cinema adaptations of Krishna stories

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of The Childhood of Krishna is precarious, as with most Indian films from the silent era. Only fragments of the film are believed to survive, with no complete known print in existence. Some surviving footage may be held in the National Film Archive of India (NFAI) or in private collections, but it has not been fully restored or made widely available. The film is considered partially lost, a common fate for early Indian cinema due to the unstable nature of early film stock and inadequate preservation facilities in the early 20th century. Some scenes or stills may survive in photographic form or as part of compilation films about early Indian cinema.