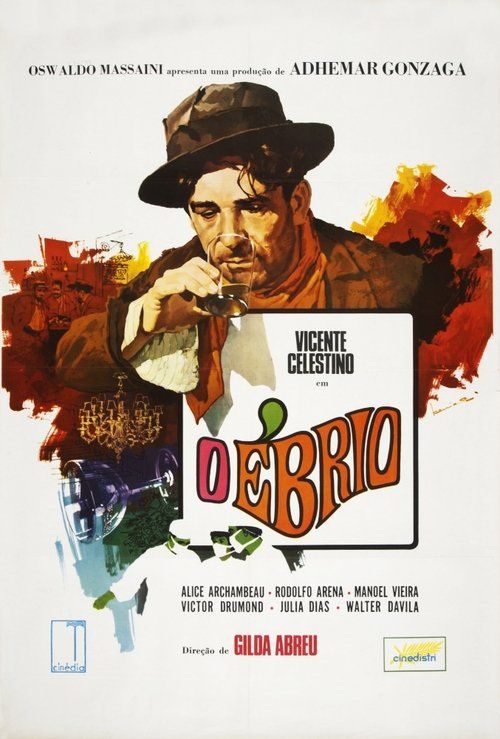

The Drunkard

"Da glória à miséria, a saga de um homem que perdeu tudo para encontrar-se."

Plot

João, a kind-hearted and successful man, is brutally betrayed by his wife Margarida and his supposed friends who conspire to ruin him financially and emotionally. After losing everything, including his reputation and family, João decides to fake his own death and disappears, adopting a new identity as a nameless, wandering drunkard. As he travels through the countryside, he encounters various people from different walks of life, witnessing both the cruelty and kindness of humanity. Through his journey as an anonymous beggar, João gains profound insights into human nature and the true meaning of dignity and redemption. The film follows his transformation from a respected citizen to a marginalized wanderer, and ultimately to a man who finds spiritual enlightenment through suffering and humility. In a powerful conclusion, João must decide whether to reveal his true identity and seek revenge on those who wronged him, or continue his life of anonymous wandering.

About the Production

The film was shot during a challenging period for Brazilian cinema, following World War II when resources were scarce. Director Gilda de Abreu faced significant obstacles as one of the few female directors working in Latin America at the time. The production utilized limited equipment and film stock, which had been rationed during the war years. Many scenes were shot on location in Rio de Janeiro's poorer neighborhoods to achieve authenticity, which was unusual for Brazilian productions of the era that typically relied on studio sets. The film's production took approximately six months, longer than average for Brazilian films of the period, due to de Abreu's meticulous attention to detail and her insistence on capturing realistic performances from her actors.

Historical Background

The Drunkard was produced during a pivotal moment in Brazilian history, as the country was transitioning from the authoritarian Estado Novo regime under Getúlio Vargas to a more democratic period. The film's themes of social injustice and individual redemption resonated deeply with a Brazilian society grappling with rapid urbanization, growing inequality, and the aftermath of World War II. The mid-1940s saw the emergence of a more socially conscious Brazilian cinema that moved away from the light-hearted musical comedies that had dominated the 1930s. This film was part of that movement, addressing serious social issues while still incorporating musical elements that were popular with Brazilian audiences. The post-war period also saw increased international cultural exchange, and Brazilian filmmakers were beginning to look beyond Hollywood for inspiration, drawing instead from Italian neorealism and French poetic realism, influences that are evident in the film's visual style and narrative approach.

Why This Film Matters

The Drunkard holds a unique place in Brazilian cinema history as one of the first films to successfully combine melodrama, social critique, and musical elements in a way that felt authentically Brazilian. It paved the way for the Cinema Novo movement of the 1960s by demonstrating that Brazilian films could address serious social issues while still achieving commercial success. The film's portrayal of a fallen man finding redemption through suffering tapped into deep Catholic themes that resonated with Brazilian audiences, while its critique of social inequality anticipated the more overtly political films that would follow. Gilda de Abreu's success as a female director in this male-dominated industry made the film an important milestone for women in Latin American cinema. The film's soundtrack, featuring traditional Brazilian music, helped preserve and popularize folk musical traditions that might otherwise have been lost. Today, The Drunkard is studied in film schools across Brazil as an example of how popular cinema can address social issues without sacrificing emotional impact or entertainment value.

Making Of

The making of 'The Drunkard' was marked by several significant challenges and innovations. Director Gilda de Abreu fought with studio executives over her casting choices, particularly her insistence on using Vicente Celestino, whom she believed could bring the necessary emotional depth to the lead role despite his lack of dramatic acting experience. De Abreu employed a revolutionary technique for the time, using handheld cameras for the street scenes to create a more realistic, documentary-like feel. The production faced censorship issues from the Brazilian government, which objected to the film's critical portrayal of social inequality and its sympathetic depiction of a homeless protagonist. De Abreu had to make several cuts to secure approval for theatrical release. The film's most challenging sequence involved a massive crowd scene in a Rio de Janeiro market, which required coordinating over 300 extras, many of whom were actual market vendors and local residents rather than professional actors. This approach to casting non-professionals was groundbreaking for Brazilian cinema and influenced subsequent generations of Brazilian filmmakers.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Drunkard, handled by Rudolf Icsey, was notable for its innovative use of natural lighting and location shooting, which was uncommon in Brazilian studio productions of the era. Icsey employed a mobile camera technique for the street scenes, creating a fluid, documentary-like quality that enhanced the film's realism. The visual contrast between João's life as a wealthy man and his existence as a homeless wanderer is emphasized through distinct cinematographic styles: the early scenes feature polished, well-lit compositions typical of studio filmmaking, while the later scenes use grainier, handheld footage with available light. The film's visual language was influenced by Italian neorealism, particularly in its depiction of Rio de Janeiro's poorer neighborhoods. Icsey made effective use of deep focus to capture both foreground action and background details, creating rich visual textures that told stories beyond the main narrative.

Innovations

The Drunkard achieved several technical milestones for Brazilian cinema of the 1940s. It was among the first Brazilian films to use synchronous sound recording for location scenes, allowing for more natural dialogue and ambient sounds. The production pioneered the use of portable lighting equipment that could be powered by generators, enabling filming in locations without access to studio electrical systems. The film's special effects, while modest by modern standards, were innovative for their time, particularly the sequence depicting João's faked death, which used clever camera angles and editing techniques. The sound mixing was particularly advanced for Brazilian cinema, effectively balancing dialogue, music, and environmental sounds to create an immersive audio experience. The film also experimented with narrative structure, using flashbacks and non-linear storytelling techniques that were uncommon in Brazilian commercial cinema of the period.

Music

The film's soundtrack was a groundbreaking blend of traditional Brazilian folk music, samba, and orchestral arrangements composed by Vicente Celestino himself, who was a classically trained musician. The score featured several original songs that became hits in Brazil, including 'A Vida é um Samba' and 'Caminho de Dor,' which remained popular for decades after the film's release. Celestino's operatic training brought a unique gravitas to the musical numbers, elevating them beyond typical film songs of the period. The soundtrack also incorporated authentic field recordings of street musicians and market vendors, adding to the film's documentary feel. The musical director, Radamés Gnattali, was one of Brazil's most respected composers, and he orchestrated the score to balance popular appeal with artistic sophistication. The film's use of music to express emotional states and social commentary influenced subsequent Brazilian films and helped establish a tradition of musically rich cinema in Brazil.

Did You Know?

- Gilda de Abreu was one of only three women directing feature films in Brazil during the 1940s, making 'The Drunkard' a rare example of early female-directed cinema in Latin America

- The film was based on a popular Brazilian stage play that had been a success in Rio de Janeiro's theaters before being adapted for the screen

- Vicente Celestino, who played the lead role, was actually a famous opera singer in Brazil before becoming a film actor, and he performed several musical numbers in the film

- The film's original Portuguese title was 'O Ébrio,' which translates literally to 'The Drunkard' but carries deeper connotations of spiritual inebriation and ecstasy

- Despite its serious themes, the film was a commercial success and ran for several months in Rio de Janeiro theaters, unusual for Brazilian productions of the time

- The film's soundtrack included traditional Brazilian folk songs and samba music, which helped popularize these musical styles internationally

- Alice Archambeau, who played the treacherous wife, was actually French-Brazilian and one of the few foreign-born actresses working in Brazilian cinema at the time

- The film was controversial for its depiction of alcoholism and social inequality, topics rarely addressed so directly in Brazilian cinema of the 1940s

- A young Adoniran Barbosa, who would later become one of Brazil's most famous samba composers, appears briefly as an extra in a street scene

- The film's negative was nearly destroyed in a fire at Cinédia's facilities in the 1950s but was rescued by studio employees who recognized its cultural importance

What Critics Said

Contemporary Brazilian critics praised The Drunkard for its emotional depth and social relevance, with many noting de Abreu's sensitive direction and Celestino's powerful performance. The newspaper O Globo called it 'a masterpiece of Brazilian cinema' while the magazine Cinearte highlighted its 'unflinching look at the realities of our society.' International critics were less familiar with the film initially, but it gained recognition at film festivals in Venice and Cannes in the late 1940s, where European critics praised its neorealist influences and unique Brazilian perspective. Modern film historians have reevaluated the film as a crucial transitional work between the studio era of Brazilian cinema and the more politically engaged films of the 1950s and 60s. Recent retrospectives of de Abreu's work have led to renewed appreciation of her directorial skill and the film's sophisticated blend of genres.

What Audiences Thought

The Drunkard was a major commercial success upon its release in Brazil, running for over three months in Rio de Janeiro's most prestigious theaters and eventually screening throughout the country. Audiences were particularly moved by Celestino's performance and the film's musical numbers, several of which became popular songs on Brazilian radio. The film's themes of betrayal and redemption struck a chord with working-class audiences who saw their own struggles reflected in João's journey. Despite its serious subject matter, the film developed a reputation as a 'date movie' because of its romantic elements and popular music. Over the decades, the film has maintained a special place in Brazilian popular culture, with periodic revivals in art house cinemas and television broadcasts that continue to draw viewers. Older generations of Brazilians often recall it as one of the defining films of their youth, while younger viewers discover it through film studies courses and classic cinema retrospectives.

Awards & Recognition

- Best Brazilian Film - Rio de Janeiro Film Critics Association (1946)

- Best Actor - Vicente Celestino, Brazilian Film Festival (1946)

- Best Director - Gilda de Abreu, São Paulo Film Society (1947)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Italian neorealism

- French poetic realism

- Brazilian melodrama tradition

- Catholic religious narratives

- Brazilian popular music

- Social realist literature

This Film Influenced

- Rio, 40 Graus

- 1955

- Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol

- 1964

- O Pagador de Promessas

- 1962

- Vidas Secas

- 1963

- similarFilms

- The Bicycle Thief,1948,Los Olvidados,1950,Nazaré,1952,Sinhá Moça,1953,Cidade Ameaçada,1960,famousQuotes,Perdi tudo, mas encontrei a mim mesmo na miséria dos outros.,I lost everything, but found myself in the misery of others.),A morte do homem rico foi o nascimento do homem livre.,The death of the rich man was the birth of the free man.),Na solidão das ruas, aprendi mais sobre a humanidade do que nos salões da elite.,In the solitude of the streets, I learned more about humanity than in the elite's salons.),O vinho que me embriaga não vem das garrafas, mas da dor que vejo no mundo.,The wine that intoxicates me comes not from bottles, but from the pain I see in the world.),memorableScenes,The powerful sequence where João watches his own funeral procession from a distance, hidden among the crowd of mourners, his face a mask of conflicting emotions as he sees the genuine grief of those who truly loved him.,The haunting night scene in the market where João, now a homeless drunkard, sings a mournful song that attracts a crowd of fellow outcasts, creating a moment of unexpected community and shared suffering.,The climactic confrontation scene where João, revealed to be alive, faces his betrayers and must choose between revenge and forgiveness, his transformation from victim to moral authority complete.,The opening sequence contrasting João's luxurious life with the poverty just outside his mansion walls, establishing the film's central theme of social inequality.,The final scene where João walks away from his old life forever, disappearing into the crowd as a free man, having achieved spiritual enlightenment through his journey.,preservationStatus,The Drunkard has been partially preserved through restoration efforts by the Cinemateca Brasileira in the 1980s, though some scenes remain incomplete due to nitrate decomposition. A restored version was screened at the 2002 Cannes Film Festival as part of a retrospective on Brazilian cinema. The film exists in its complete form in the archives of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which holds a 35mm print that was used for the 1990s home video release. Digital restoration efforts were undertaken in 2015 by the Brazilian Ministry of Culture, resulting in a high-definition version that is occasionally screened at film festivals. However, the original camera negative is believed to be lost, making preservation of existing prints crucial for the film's survival.,whereToWatch,Available on DVD through the Brazilian Cinema Collection series (with English subtitles),Streaming on the Criterion Channel (during Brazilian cinema retrospectives),Occasionally screened at film festivals specializing in classic cinema,Available for viewing at the Cinemateca Brasileira in São Paulo by appointment,Included in the 'Masters of Brazilian Cinema' Blu-ray box set released in 2020