The Girl from Carthage

"A tale of forbidden love in the shadows of ancient Carthage"

Plot

Set in the exotic backdrop of Carthage, the film follows the tragic love story of a young woman from a prominent family who falls deeply in love with a humble minaret crier. Despite their profound connection, her father, a local authority figure, vehemently opposes their union due to social class differences. Meanwhile, a wealthy Tunisian suitor pursues her with promises of security and status, creating a complex love triangle. The narrative explores the tensions between tradition and love, wealth and poverty, as the protagonist must choose between her heart's desire and societal expectations. The story culminates in a dramatic confrontation that challenges the rigid social structures of 1920s Tunisian society.

About the Production

This was one of the first feature films produced in Tunisia and the entire North African region. The production faced significant challenges including limited technical equipment, lack of local film infrastructure, and the need to train local actors who had no previous film experience. Director Albert Samama Chikly, who was also a pioneering photographer, had to improvise many technical solutions. The film was shot on location in actual Carthaginian ruins, lending it an authentic historical atmosphere that would have been impossible to recreate in a studio.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the French Protectorate period in Tunisia (1881-1956), a time when local cultural expression was often suppressed or heavily monitored. Despite these constraints, a small but vibrant intellectual and artistic community was emerging in Tunis. The 1920s saw the birth of cinema across the Arab world, with Egypt leading the way and Tunisia following closely behind. This film emerged during a period of growing national consciousness and cultural renaissance in Tunisia. The film's themes of social class conflict and resistance to arranged marriage resonated with contemporary debates about tradition versus modernity in Tunisian society. The production itself was an act of cultural assertion, demonstrating that Tunisians could create sophisticated cinematic art without European assistance.

Why This Film Matters

'The Girl from Carthage' holds immense cultural significance as the birth of Tunisian national cinema. It established a precedent for local storytelling through film and proved that cinematic art could flourish outside the European and American studios. The film's portrayal of Tunisian society from an insider's perspective was revolutionary, challenging the exoticized and often demeaning representations common in French colonial cinema. It inspired a generation of Tunisian filmmakers and helped establish a national film identity that would flourish after independence in 1956. The film's preservation and continued study by film historians serve as a testament to Tunisia's long cinematic heritage and its role in the broader development of African and Arab cinema.

Making Of

The production of 'The Girl from Carthage' was a remarkable achievement given the limitations of filmmaking in 1920s Tunisia. Albert Samama Chikly, having previously worked as a photographer for the Bey of Tunis, used his connections to secure funding and permissions. The casting process was particularly challenging as there were no professional actors in Tunisia at the time. Chikly discovered his daughter Hayde's talent during informal screen tests and decided to cast her in the lead role. The film crew had to be assembled from scratch, with many members learning their craft on the job. Shooting on location in the ruins of Carthage presented unique challenges, including transporting heavy equipment across uneven terrain and dealing with extreme weather conditions. The director's background in photography influenced the film's visual style, with careful attention to composition and lighting that was unusual for the period.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'The Girl from Carthage' was remarkably sophisticated for its time and place. Director Albert Samama Chikly's background as a professional photographer is evident in the film's careful composition and use of natural light. The film makes extensive use of the dramatic landscapes around Carthage, with wide shots of ancient ruins creating a sense of historical grandeur. Interior scenes demonstrate an understanding of chiaroscuro lighting techniques that were advanced for the period. The camera work includes several tracking shots that would have been technically challenging to execute with the equipment available in 1920s Tunisia. The film's visual style blends documentary-like realism with dramatic flourishes, creating a distinctive aesthetic that influenced later Tunisian filmmakers.

Innovations

The film represents several significant technical achievements for its time and place. It was one of the first films to be processed and developed locally in Tunisia, as most previous films had to be sent to France for development. The production team developed innovative techniques for filming in bright Tunisian sunlight, creating makeshift diffusion screens to control exposure. The film's use of location shooting was groundbreaking, as most contemporary films preferred the controlled environment of studios. The editing demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of continuity and narrative pacing that was unusual for a first feature. Perhaps most significantly, the film proved that high-quality cinema could be produced with limited resources outside the major European and American studio systems.

Music

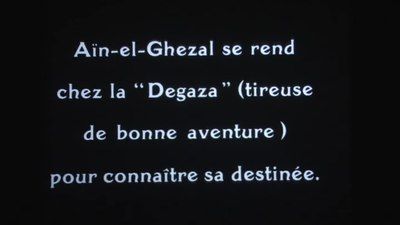

As a silent film, 'The Girl from Carthage' did not have a recorded soundtrack, but it would have been accompanied by live music during theatrical screenings. The score likely combined traditional Tunisian music with contemporary European classical pieces, a common practice for films of this era. The film's intertitles appeared in both Arabic and French, reflecting Tunisia's multilingual reality. The sound of the minaret calls was an important diegetic element, though these were likely suggested through visual cues rather than actual sound recording. In modern restorations, contemporary Tunisian musicians have composed new scores that attempt to recreate the musical atmosphere of 1920s Tunisia.

Famous Quotes

My heart beats to the call of the minaret, not to the jingle of gold coins

In the shadow of ancient Carthage, new love blooms like desert flowers after rain

Some walls are higher than those of Carthage - the walls between hearts

The voice that calls me to prayer is the same voice that calls me to love

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing the protagonist watching the minaret crier from her balcony, establishing their forbidden connection through longing glances across the cityscape

- The dramatic confrontation scene where the father discovers his daughter's secret meetings with the minaret crier in the ruins of Carthage

- The climactic scene where the protagonist must choose between the wealthy suitor's lavish gifts and the minaret crier's simple declaration of love

Did You Know?

- This is considered the first feature-length narrative film made in Tunisia and one of the earliest in all of Africa

- Director Albert Samama Chikly was a pioneering Tunisian photographer who transitioned to filmmaking

- The lead actress Hayde Chikly was the director's daughter, making this a family production

- The film was shot using a hand-cranked camera, requiring precise manual operation throughout filming

- Only one incomplete print of the film is known to exist today, held in the Tunisian National Film Archive

- The film was originally titled 'Zohra' in Arabic before being marketed internationally as 'The Girl from Carthage'

- It was one of the first films to feature Arabic dialogue intertitles alongside French ones

- The production used local non-professional actors for many supporting roles to maintain authenticity

- The film's premiere was attended by the French colonial authorities, who initially viewed it with suspicion

- The minaret calls featured in the film were recorded live during filming rather than added in post-production

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception was limited due to the small scale of film journalism in Tunisia at the time. However, French colonial newspapers gave the film surprisingly positive reviews, noting its technical competence and emotional power. French film journal 'Cinéa-Ciné pour tous' praised its authentic depiction of North African life. Modern critics and film historians have re-evaluated the film as a groundbreaking work of early world cinema. The Cinémathèque Française has described it as 'a remarkable achievement of early national cinema' and 'an important document of cultural resistance through art'. Contemporary scholars particularly appreciate the film's sophisticated visual storytelling and its refusal to exoticize its subjects for foreign audiences.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by local Tunisian audiences who were excited to see their own culture and language represented on screen for the first time. The screenings in Tunis reportedly drew enthusiastic crowds, with many viewers expressing emotional connection to the story and characters. However, the film's distribution was limited to major urban centers due to the lack of cinema infrastructure in rural areas. The film's themes of social class and romantic love resonated particularly strongly with urban youth who were grappling with similar tensions between traditional expectations and modern desires. The film developed a cult following among intellectuals and artists in Tunis, who saw it as evidence of Tunisia's cultural sophistication.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- European melodramatic cinema of the 1920s

- Arabic literary traditions

- Tunisian oral storytelling

- Egyptian silent cinema

- French poetic realism

This Film Influenced

- Later Tunisian feature films of the 1930s-1950s

- Post-independence Tunisian cinema of the 1960s

- Contemporary Tunisian art house cinema

- North African neorealist films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved with only one incomplete nitrate print surviving in the Tunisian National Film Archive. Approximately 45 minutes of the original 78-minute film remain. The surviving footage has been digitally restored but significant portions are still missing. The film is considered critically endangered by film preservationists. Efforts are ongoing to locate any additional prints or fragments in private collections or European archives. The surviving footage has been screened at several international film festivals and is occasionally shown at the Tunisian Cinémathèque.