The House on the Volcano

Plot

An aging drilling foreman reflects on his past experiences in the oil fields of pre-revolutionary Baku, recounting the brutal suppression of a workers' strike that took place years earlier. Through his memories, the film depicts the harsh conditions faced by oil workers and their struggle for better working conditions and rights. The narrative shifts between the present day and the past, showing the foreman's current life while vividly recreating the violent confrontation between striking workers and authorities. The film culminates in a powerful portrayal of the workers' sacrifice and the eventual triumph of the revolutionary spirit, serving as both a personal story and a broader historical allegory about class struggle and revolutionary change.

About the Production

The House on the Volcano was one of the earliest feature films produced by the newly established Armenian film studio Armenfilm. Director Hamo Bek-Nazaryan, considered the father of Armenian cinema, used actual oil field locations in Baku to add authenticity to the production. The film was made during the silent era but included synchronized music and sound effects using the Phonofilm system, making it one of the early experiments with sound in Soviet cinema. The production faced challenges due to the remote filming locations and the need to recreate historical events from the early 20th century.

Historical Background

The House on the Volcano was produced during a crucial period in Soviet cultural history, when the government was encouraging the development of national cinemas within the various Soviet republics. The film deals with the Baku oil workers' strikes of 1904-1905, which were significant precursors to the 1905 and 1917 revolutions. By 1928, the Soviet Union was undergoing rapid industrialization under Stalin's First Five-Year Plan, and films about workers' struggles were officially encouraged as propaganda. However, this particular film was notable for its relatively nuanced portrayal of the workers' suffering and the brutality of the suppression, which made it controversial in later years. The film also reflects the growing sophistication of Soviet cinema in the late 1920s, moving from pure propaganda toward more artistically ambitious works that still served ideological purposes.

Why This Film Matters

The House on the Volcano holds a special place in film history as one of the foundational works of Armenian cinema and an important example of early Soviet national cinema. It established Hamo Bek-Nazaryan as a major director and helped define the aesthetic and thematic concerns of Armenian filmmaking for decades to come. The film was groundbreaking in its depiction of class struggle from a non-Russian perspective, highlighting the multi-ethnic nature of the Soviet revolutionary experience. Its focus on the Baku oil industry also documented an important aspect of Soviet economic history. The film's preservation and restoration in the 1970s sparked renewed interest in early Soviet cinema and led to a reevaluation of Bek-Nazaryan's contribution to world cinema. Today, it is studied as an important example of how national identities were expressed within the framework of Soviet art.

Making Of

The production of The House on the Volcano was a significant undertaking for the young Armenian film industry. Director Hamo Bek-Nazaryan, who had studied under influential Soviet filmmakers, brought a sophisticated visual style to the project. The film was shot during the summer of 1928, with the crew facing extreme heat and difficult working conditions in the Baku oil fields. Bek-Nazaryan insisted on using real oil workers as extras in the strike scenes, which required extensive coordination with local unions and party officials. The film's recreation of the historical strike was meticulously researched, with the director consulting archives and interviewing survivors of the actual events. The production employed innovative camera techniques for the time, including low-angle shots of the oil derricks and dynamic tracking shots during the confrontation scenes. The synchronized musical score was recorded separately and then matched to the film during projection, a cutting-edge technique for 1928.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The House on the Volcano, handled by Dmitri Feldman, was considered innovative for its time. The film features striking visual compositions that contrast the towering oil derricks against the flat Baku landscape, creating powerful metaphors for industrial might and human vulnerability. Feldman employed dramatic low-angle shots to emphasize the scale of the oil machinery and high-angle shots during the strike scenes to convey the chaos of the confrontation. The use of natural lighting in the outdoor scenes and the careful composition of group scenes showing the workers' solidarity were particularly praised. The film also features some of the earliest examples of tracking shots in Soviet cinema, used to follow the movement of workers during the strike sequences. The visual style combines elements of Soviet montage theory with more traditional narrative techniques, creating a distinctive aesthetic that influenced later Armenian filmmakers.

Innovations

The House on the Volcano was technically innovative for its time in several respects. It was one of the first films to use the Phonofilm system for synchronized sound in the Soviet Union, predating the widespread adoption of sound cinema. The production employed mobile camera units to film in the challenging terrain of the Baku oil fields, requiring specially designed equipment that could operate in the industrial environment. The film's recreation of historical events required elaborate crowd scenes involving hundreds of extras, which was coordinated using early forms of production management techniques. The cinematography featured complex lighting setups to capture both the industrial landscape and intimate character scenes. The film also experimented with narrative structure, using flashbacks and memory sequences that were relatively sophisticated for silent cinema storytelling.

Music

The House on the Volcano featured a synchronized musical score composed by Aram Khachaturian in one of his earliest professional works. The score incorporated Armenian folk melodies and revolutionary songs, reflecting the film's dual identity as both a national and Soviet work. The music was recorded using the Phonofilm system, which allowed for synchronized sound with the film projection. Khachaturian's composition included leitmotifs for the main characters and themes representing the oil industry, workers' solidarity, and revolutionary struggle. The soundtrack also featured sound effects of drilling machinery and crowd noises, adding to the film's realism. This early experiment with synchronized sound was technically ambitious for 1928 and demonstrated the Soviet film industry's rapid technological development during this period.

Famous Quotes

The oil may flow from the earth, but freedom flows from the hearts of men

We may be broken today, but our children will stand tall

In the shadow of the derricks, we found our humanity

The volcano may sleep, but the fire in our hearts never dies

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing the vast oil fields of Baku at dawn, with the silhouettes of drilling rigs against the rising sun

- The dramatic confrontation scene where striking workers face armed authorities, shot from multiple angles to emphasize the chaos and violence

- The foreman's monologue sequence where he recounts the events of the strike, using innovative flashback techniques

- The final scene showing the next generation of workers continuing the struggle, symbolizing the ongoing nature of the revolutionary fight

Did You Know?

- The House on the Volcano was director Hamo Bek-Nazaryan's third feature film and established him as a major figure in Soviet cinema

- The film was partially shot on location at actual oil fields in Baku, using real drilling equipment and facilities

- It was one of the first Soviet films to depict the Baku oil workers' strikes of the early 1900s, a significant event in Russian revolutionary history

- The film's title refers to the mud volcanoes common in the Baku region, symbolizing both the geographical setting and the explosive social tensions

- Despite being a silent film, it featured a synchronized musical score composed by Armenian composer Aram Khachaturian in one of his earliest film works

- The film was banned for several years in the 1930s during Stalin's purges due to its depiction of workers' struggle, which was deemed 'counter-revolutionary' at the time

- Original prints of the film were thought lost until a complete copy was discovered in the Gosfilmofond archive in Moscow in the 1970s

- The film used non-professional actors from the Baku oil fields to add authenticity to the workers' scenes

- It was one of the first films to be produced by Armenfilm after its establishment in 1923

- The film's cinematographer, Dmitri Feldman, later became one of the most prominent cinematographers in Soviet cinema

What Critics Said

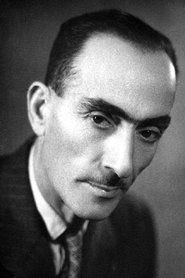

Upon its release in 1928, The House on the Volcano received generally positive reviews from Soviet critics, who praised its powerful imagery and authentic depiction of workers' life. The film was particularly noted for its innovative cinematography and the strong performance by Hrachia Nersisyan in the lead role. International critics at film exhibitions in Vienna and Paris also recognized the film's artistic merits, with some comparing it favorably to the works of Eisenstein and Pudovkin. However, during the Stalinist era, the film fell out of favor and was criticized for its 'formalist tendencies' and insufficiently optimistic portrayal of revolutionary struggle. In modern times, film historians have reevaluated the work as a significant achievement in early Soviet cinema, appreciating its artistic qualities and its importance in the development of Armenian film culture.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary audience reception to The House on the Volcano was generally positive, particularly among workers and intellectuals who appreciated its realistic portrayal of labor struggles. The film resonated strongly in Baku, where many viewers recognized locations and events from their own history or that of their parents. In Armenia, the film was celebrated as a major achievement of national cinema and drew large crowds during its theatrical run. However, like many Soviet films of the era, its audience was limited to urban centers with proper cinema facilities. The film's ban in the 1930s meant that subsequent generations were unable to see it until its rediscovery in the 1970s, when it was screened at retrospectives and film festivals, introducing it to new audiences who appreciated its historical significance and artistic qualities.

Awards & Recognition

- Honored Film of the Armenian SSR (1929)

- Best Soviet Film at the International Film Exhibition in Vienna (1929)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Battleship Potemkin (1925)

- Strike (1925)

- The End of St. Petersburg (1927)

- October: Ten Days That Shook the World (1928)

This Film Influenced

- Zangezur (1938)

- Pepo (1935)

- The Girl from Ararat Valley (1940)

- Hello, That's Me! (1966)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was believed lost for decades until a complete nitrate print was discovered in the Gosfilmofond archive in Moscow in 1972. The film underwent restoration by the Armenian State Film Archive in 1975, with additional restoration work completed in 2005 as part of a Soviet cinema preservation project. The restored version is now preserved in both the Gosfilmofond and the Armenian National Film Archive. While some deterioration is visible due to the age of the original materials, the film is considered to be in relatively good condition for a silent film of its era. Digital restoration efforts have made the film accessible to modern audiences while preserving its historical and artistic integrity.