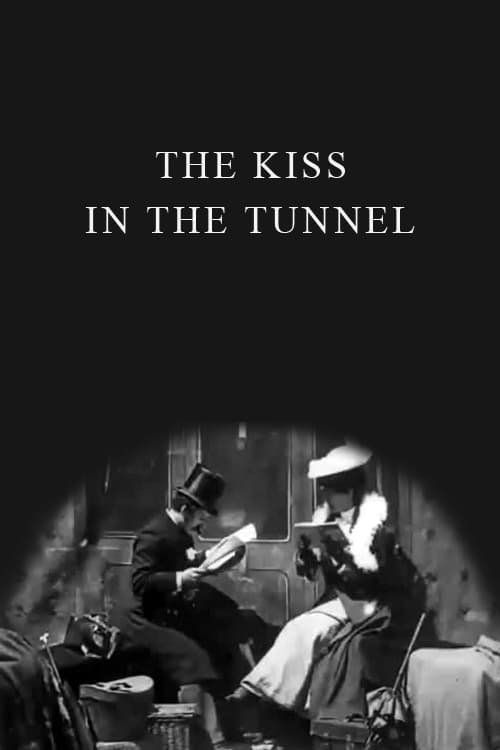

The Kiss in the Tunnel

Plot

The Kiss in the Tunnel presents a groundbreaking narrative sequence that begins with Cecil Hepworth's footage of a train approaching and entering Shilla Mill Tunnel. As the train disappears into darkness, the film cuts to George Albert Smith's shot inside a train carriage where a gentleman and lady, taking advantage of the momentary darkness, quickly share a passionate kiss. The couple immediately composes themselves as the train emerges from the tunnel, with the film cutting back to Hepworth's footage showing the train exiting into daylight. This simple yet innovative sequence creates a complete narrative arc using three distinct shots, establishing cause and effect through editing rather than relying on a single continuous take.

Director

About the Production

This film represents one of cinema's earliest examples of collaborative production between two pioneering filmmakers. George Albert Smith filmed the interior carriage scene featuring himself and his wife Laura Bayley in a studio setting, while Cecil Hepworth provided the exterior train footage from his earlier film 'View From An Engine Front - Shilla Mill Tunnel'. The two distinct films were cleverly edited together to create a seamless narrative experience. The filming of the train sequence required mounting a camera on the front of a moving locomotive, a technically challenging feat for 1899 that risked both equipment and operator safety.

Historical Background

The Kiss in the Tunnel was created during the Victorian era in 1899, a pivotal moment in cinema's infancy when filmmakers were transitioning from mere recording of reality to storytelling through the medium. This period saw rapid technological advancements in film equipment and growing public fascination with moving pictures. The British film industry, centered around Brighton and London, was particularly innovative, with pioneers like Smith and Hepworth experimenting with techniques that would become fundamental to cinema. The film emerged just four years after the first public film screenings in Europe, at a time when audiences were still marveling at the basic ability to capture and project moving images. The Victorian context also makes the brief kiss scene particularly noteworthy, as public displays of affection were generally frowned upon in this era, making the film subtly transgressive for its time.

Why This Film Matters

The Kiss in the Tunnel holds enormous cultural significance as a foundational text in the development of narrative cinema. Its innovative use of editing to create cause and effect relationships between shots established a template that would become standard practice in filmmaking. The film represents one of the earliest examples of what would later be termed 'cross-cutting' or 'parallel editing', techniques that remain central to cinematic storytelling today. Its combination of spectacle (the thrilling train ride) with intimacy (the stolen kiss) demonstrated cinema's unique ability to juxtapose different scales of experience. The film also reflects Victorian attitudes toward romance and propriety, using the darkness of the tunnel as a metaphorical and literal cover for forbidden intimacy. Its preservation and continued study make it an invaluable document of cinema's transition from novelty to art form.

Making Of

The creation of The Kiss in the Tunnel represents a fascinating example of early film collaboration and innovation. George Albert Smith, already established as a creative force in British cinema, conceived the idea of combining his intimate carriage scene with Hepworth's spectacular train footage. The interior scene was filmed in Smith's Brighton studio using a simple set designed to resemble a train carriage, with Smith himself playing the male lead alongside his wife Laura. The technical challenge of mounting a camera on a moving locomotive for Hepworth's footage required innovative engineering solutions of the time. Smith's decision to edit these disparate elements together was revolutionary, as most films of this era consisted of single, continuous shots. The editing process itself was done by physically cutting and splicing the film strips, a meticulous craft that Smith had perfected through his work with the Warwick Trading Company.

Visual Style

The cinematography in The Kiss in the Tunnel represents a remarkable synthesis of two distinct early film techniques. Hepworth's exterior shots employ what was known as 'phantom ride' cinematography, with the camera mounted on the front of a locomotive to create the illusion of flying through space. This technique required specialized mounting equipment and careful timing to capture the tunnel entrance and exit. Smith's interior carriage scene demonstrates his mastery of close-up photography, using the confined space to create intimacy and focus attention on the actors' expressions. The lighting in the carriage scene was carefully controlled to suggest the darkness of the tunnel while still allowing the action to be visible. The transition between the bright exterior shots and the darker interior creates a natural contrast that enhances the narrative effect. The film's cinematography shows an early understanding of how camera placement and movement could affect audience perception and emotion.

Innovations

The Kiss in the Tunnel showcases several significant technical achievements for its era. Most importantly, it demonstrates early mastery of film editing, a technique still in its infancy in 1899. The seamless integration of footage from two different cameras and locations represents a sophisticated understanding of continuity. Hepworth's train footage required innovative camera mounting solutions to withstand the vibrations and movement of a locomotive, a technical challenge that many early filmmakers avoided. Smith's interior scene shows advanced understanding of lighting control in confined spaces, using artificial light to simulate the tunnel's darkness while maintaining visibility. The film's preservation of consistent exposure across different shooting conditions indicates careful technical planning. The physical splicing of the film strips required precision cutting and alignment, as any misalignment would be immediately apparent to viewers. These technical innovations collectively represent a significant step forward in the craft of filmmaking.

Music

As a silent film from 1899, The Kiss in the Tunnel was originally exhibited without synchronized sound. During its initial screenings, the film would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small orchestra in music halls, or possibly a phonograph recording in more sophisticated venues. The musical accompaniment would have been chosen to enhance the film's moods: exciting music for the train sequences, romantic music for the kiss scene, and triumphant music for the tunnel exit. Some exhibitors might have used sound effects such as train whistles or tunnel echoes to enhance the experience. Modern screenings and presentations of the film often feature newly composed scores that attempt to recreate the musical styles of the late Victorian period while acknowledging the film's historical importance. The absence of original musical documentation means that modern accompaniments are interpretive rather than historically accurate.

Famous Quotes

(Silent film - no dialogue, but the action speaks: The brief, stolen kiss in the darkness of the tunnel represents the film's entire narrative message)

Memorable Scenes

- The innovative transition from the exterior train shot entering the tunnel to the intimate interior carriage scene where the couple shares their kiss, creating one of cinema's earliest examples of narrative editing and establishing cause-and-effect relationships between shots

Did You Know?

- This film is considered one of the earliest examples of narrative editing in cinema history, using three separate shots to tell a complete story

- The film combines work from two of Britain's most important early filmmakers: George Albert Smith and Cecil Hepworth

- Laura Bayley, who plays the woman, was George Albert Smith's wife in real life and frequently appeared in his films

- The train footage was originally shot by Hepworth as a standalone film called 'View From An Engine Front - Shilla Mill Tunnel'

- This film predates Edwin S. Porter's 'The Great Train Robbery' (1903) by four years in its use of narrative editing

- The kiss scene was considered quite daring for Victorian audiences, though brief and innocent by modern standards

- The tunnel used in the film, Shilla Mill Tunnel, was part of the Brighton railway line and still exists today

- Smith was a former stage magician who applied his understanding of visual tricks to early cinema

- The film demonstrates Smith's pioneering use of close-up shots, which were rare in this era of cinema

- This type of 'phantom ride' film was extremely popular in the late 1890s, giving audiences the thrilling sensation of being on a moving train

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of The Kiss in the Tunnel is difficult to document due to the limited film journalism of 1899, but trade publications of the era noted its clever construction and audience appeal. Modern film historians and critics universally recognize the film as a landmark achievement in early cinema. Scholars such as Charles Musser and Barry Salt have extensively analyzed its editing techniques and their influence on subsequent film development. The British Film Institute includes it among the most important early British films, noting its role in establishing narrative conventions. Contemporary critics praise its sophisticated understanding of cinematic time and space, particularly remarkable given the medium's infancy. The film is frequently cited in academic studies of early cinema as evidence of the rapid evolution of film language in its first decade.

What Audiences Thought

Victorian audiences reportedly responded enthusiastically to The Kiss in the Tunnel, particularly enjoying the thrilling sensation of the train ride combined with the romantic element. The film was popular in music halls and fairground shows, where it was often part of mixed programs of short films. The brief kiss scene, while innocent by modern standards, added an element of mild scandal that likely enhanced its appeal to Victorian viewers. Contemporary accounts suggest audiences appreciated the cleverness of the editing, even if they didn't fully understand the technical innovations involved. The film's combination of spectacle and romance made it a reliable crowd-pleaser, and it continued to be shown for several years after its initial release, indicating sustained popular appeal. Modern audiences viewing the film in retrospectives and archives often express surprise at its sophistication relative to its age.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Georges Méliès's narrative trick films

- Edison and Lumière's actuality films

- Stage magic and theatrical traditions

- Victorian literature and drama

- Early photography techniques

- Music hall entertainment traditions

This Film Influenced

- Edwin S. Porter's 'The Great Train Robbery' (1903)

- George Albert Smith's 'Mary Jane's Mishap' (1903)

- Cecil Hepworth's 'Rescued by Rover' (1905)

- D.W. Griffith's early Biograph shorts

- Early chase films and railway melodramas

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved and is available through various film archives including the British Film Institute (BFI) National Archive. The BFI holds a 35mm print of the film, which has been digitized for preservation and access. The film survives in relatively good condition considering its age, though some deterioration is evident. Both components of the film (Smith's carriage scene and Hepworth's train footage) have been preserved, allowing modern audiences to appreciate the complete work as originally intended. The film is frequently included in retrospectives of early cinema and is available on various DVD collections and streaming platforms specializing in classic and silent films.