The Life and Passion of Jesus Christ

Plot

This 1903 French silent epic presents a comprehensive dramatization of the life of Jesus Christ through a series of meticulously staged tableaux vivants. The film begins with the Annunciation and Nativity, progressing through key biblical events including Jesus's baptism, miracles, the Sermon on the Mount, and his ministry. The narrative intensifies with the Last Supper, Jesus's betrayal by Judas, his trial before Pontius Pilate, the harrowing crucifixion sequence, and ultimately his resurrection and ascension into heaven. Each scene was carefully composed to resemble religious paintings of the era, with actors posed dramatically against elaborate painted backdrops and detailed sets. The film was designed to be shown with live musical accompaniment and was one of the most ambitious religious productions of early cinema.

Director

About the Production

The film utilized the Pathécolor stencil coloring process, one of the earliest methods of adding color to motion pictures. Each frame was hand-colored by women workers using stencils, a laborious process that took months to complete. The production involved over 200 actors and extras, with elaborate costumes and props specifically designed for each biblical scene. The film was shot in multiple sequences that could be shown separately or as a complete feature, giving exhibitors flexibility in presentation.

Historical Background

This film was produced during a pivotal moment in cinema history when the medium was transitioning from simple novelty acts to narrative storytelling. In 1903, the film industry was still in its infancy, with most productions lasting only a few minutes. The Wright brothers' first flight occurred the same year, symbolizing a period of technological innovation across all fields. In France, the separation of church and state was a contentious political issue, making a religious film production both commercially promising and potentially controversial. The film emerged from the Pathé Frères company, which had established itself as a dominant force in early cinema through technical innovations and aggressive international distribution. This production represented one of the first attempts to create a serious, respectful treatment of religious subject matter in cinema, setting precedents for how sacred stories could be adapted to the new medium.

Why This Film Matters

This film holds immense cultural significance as one of the earliest attempts to bring biblical narratives to the screen, establishing conventions that would influence religious filmmaking for decades. It demonstrated that cinema could handle serious, sacred subjects with dignity and artistic ambition, helping to legitimize film as a medium capable of more than mere entertainment. The film's international success proved that religious stories had universal appeal across cultural and linguistic boundaries, encouraging other producers to tackle similar subjects. Its use of color, though primitive by modern standards, showed audiences the potential for visual spectacle in cinema. The film also established the tableau vivant style as an early cinematic language, influencing how visual storytelling would develop. Its preservation and continued study make it an invaluable document of early cinematic techniques and artistic ambitions, while its subject matter reflects the central role of Christianity in Western culture at the turn of the 20th century.

Making Of

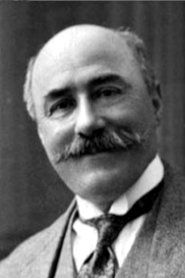

The production of 'The Life and Passion of Jesus Christ' was a monumental undertaking for its time, requiring months of preparation and filming. Director Ferdinand Zecca, who had previously worked as a magician and theater director, brought theatrical sensibilities to the film's staging. The cast was composed largely of stage actors from Paris theaters, many of whom were initially skeptical about appearing in the new medium of cinema. The elaborate sets were constructed in Pathé's studio in Vincennes, with painted backdrops designed to resemble classical religious paintings. The hand-coloring process involved teams of women working in factory-like conditions, each specializing in applying specific colors to the film frames. The production faced challenges with the primitive camera equipment of the era, requiring multiple takes for many scenes due to technical failures. The film's success established Pathé as a major international film producer and demonstrated the commercial viability of feature-length narrative cinema.

Visual Style

The cinematography reflects the technical limitations and artistic conventions of 1903, utilizing static camera positions typical of early cinema. The film employs long takes that capture entire scenes in single shots, creating a theatrical presentation style. The use of Pathécolor stencil coloring adds visual richness to key scenes, with careful attention to symbolic color choices - blues for holy figures, reds for moments of passion, and gold for divine elements. The lighting is primarily natural and flat, characteristic of the period's technical capabilities, but is enhanced by the painted backdrops and costumes designed to maximize visual impact. The framing often mimics the composition of religious paintings, with careful attention to creating balanced, symmetrical compositions that would be familiar to contemporary audiences from church art.

Innovations

The film's most significant technical achievement was its extensive use of the Pathécolor stencil coloring process, one of the earliest successful methods for adding color to motion pictures. Each frame was hand-colored through stencils, allowing for precise application of multiple colors. The production also pioneered techniques for creating large-scale biblical sets within the constraints of early studio spaces. The film demonstrated advanced continuity editing for its period, with scenes carefully sequenced to create a coherent narrative arc. Its length of 44 minutes was remarkable for 1903, pushing the boundaries of what was considered possible in feature filmmaking. The production also developed new methods for crowd control and directing large groups of extras in complex scenes.

Music

As a silent film, it was originally presented with live musical accompaniment, typically consisting of organ music or small orchestral ensembles. Pathé provided suggested musical cues for exhibitors, recommending appropriate pieces for each scene - somber music for the crucifixion, triumphant themes for the resurrection, etc. Some presentations included a live narrator who would read biblical passages or explain the action between scenes. The musical accompaniment was crucial to the emotional impact of the film, with many venues commissioning original scores or adaptations of classical religious music. The recommended soundtrack often included works by composers like Bach and Handel, whose music was in the public domain and familiar to audiences.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, there are no spoken dialogue quotes, but intertitles included biblical passages such as 'Verily, I say unto you, one of you shall betray me' and 'It is finished'

Memorable Scenes

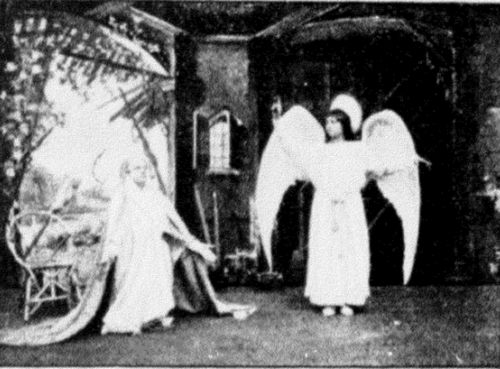

- The Annunciation scene with the angel appearing to Mary surrounded by divine light

- The Sermon on the Mount with Jesus addressing a large crowd on a hillside

- The Last Supper with the apostles arranged in a composition reminiscent of Leonardo da Vinci's painting

- The Crucifixion sequence, particularly powerful in its simplicity and emotional impact

- The Resurrection scene with the empty tomb and angelic figures

- The Ascension finale with Jesus rising into the heavens above the disciples

Did You Know?

- This was one of the first feature-length films ever made, predating most other early narrative features by several years

- The film was so popular that it was still being shown in theaters as late as the 1920s, nearly two decades after its release

- Pathé created multiple versions of the film for different international markets, with varying running times and scene selections

- The hand-coloring process used in this film required up to 12 different color stencils per frame, making it extremely labor-intensive

- The film was originally distributed in 27 separate scenes, which could be shown individually or as a complete program

- Madame Moreau, who played the Virgin Mary, was a stage actress who had never appeared in films before this production

- The crucifixion scene was considered so realistic and potentially controversial that some exhibitors chose to omit it from their presentations

- The film's success led to a wave of biblical epics in the following decade, establishing a new genre in cinema

- A complete original print of the film was discovered in the Netherlands in the 1970s, allowing for proper restoration

- The production used real locations in and around Paris for some outdoor scenes, unusual for the period when most filming was done entirely indoors

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's ambitious scope and respectful treatment of religious subject matter, with many newspapers commenting on its ability to move audiences emotionally despite the limitations of silent cinema. The trade press particularly noted the technical achievements in set design and the innovative use of color. Modern film historians consider it a landmark achievement in early cinema, praising its influence on the development of narrative film techniques and its role in establishing the biblical epic genre. Critics today analyze it as an important example of how early cinema adapted established artistic traditions from theater and painting to create a new visual language.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with audiences worldwide, reportedly drawing large crowds in both religious and secular venues. Many viewers reported being deeply moved by the crucifixion and resurrection scenes, despite the primitive nature of the film technology. Church groups both praised and criticized the production - some welcomed it as a tool for religious education, while others objected to the commercialization of sacred stories. The film's popularity led to repeat viewings by many audience members, unusual for the period when most films were seen only once. Its success across different countries and cultures demonstrated the universal appeal of its subject matter and helped establish cinema as a medium capable of addressing profound human experiences.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Classical Religious Paintings

- Passion Plays

- Tableaux Vivants Theater

- Biblical Illustrations

- Catholic Iconography

- Mystery Plays

This Film Influenced

- From the Manger to the Cross (1912)

- Intolerance (1916)

- The King of Kings (1927)

- The Ten Commandments (1923)

- Ben-Hur (1925)

- The Gospel According to Matthew (1964)

- The Passion of the Christ (2004)

- Jesus of Nazareth (1977)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been partially preserved with several versions existing in different archives around the world. A complete 44-minute version was discovered and restored in the 1970s by the Cinémathèque Française. The restored version includes the original hand-coloring and has been preserved on safety film stock. Some shorter versions and individual scenes exist in various archives including the Library of Congress, the British Film Institute, and the Museum of Modern Art. The restoration work has been ongoing, with digital versions created to ensure long-term preservation of this important early film.