The Life of Matsu the Untamed

"The untamed spirit of a common man touches the hearts of all"

Plot

Matsugoro, a poor but spirited rickshaw driver in a small Japanese town, becomes beloved by the community for his cheerful optimism and willingness to help others. When he discovers a young boy named Toshio injured in the street, Matsugoro rushes to his aid and is subsequently hired by the boy's wealthy parents as their personal driver. Despite the class differences between himself and his employers, Matsugoro's genuine kindness and unwavering loyalty endear him to the family, particularly to young Toshio who comes to see him as a father figure. As their bond deepens, Matsugoro faces challenges from both social prejudice and personal circumstances, yet his untamed spirit and devotion to those he cares about remain unbroken. The story ultimately explores themes of class division, loyalty, and the transcendent power of human connection during a turbulent period in Japanese history.

About the Production

Filmed during the height of World War II, this production faced significant challenges including material shortages, government censorship requirements, and the need to align with wartime propaganda directives. Director Hiroshi Inagaki had to navigate strict government oversight while maintaining the film's humanistic elements. The production utilized limited resources due to wartime rationing, affecting everything from film stock to set construction. Despite these constraints, the film managed to capture authentic period details of early 20th century Japanese urban life.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a critical period of World War II when Japan was facing increasing military setbacks and severe domestic hardships. By 1943, the Japanese government had implemented strict controls over all cultural production, including cinema, through the Film Law of 1939 which mandated that all films serve national policy and morale. The film industry was consolidated under government control, with resources severely rationed and content heavily censored. Despite these constraints, some filmmakers like Hiroshi Inagaki managed to create works that maintained artistic integrity while navigating the political requirements. The film's release in December 1943 came at a time when Japanese cities were beginning to experience Allied bombing raids, and the civilian population was facing increasing hardships including food shortages and forced labor. The film's emphasis on human dignity, social harmony, and the strength of common people resonated with audiences seeking relief from the harsh realities of war. The rickshaw driver as a protagonist represented the ideal of the common Japanese citizen who maintains honor and dignity despite difficult circumstances, a theme that aligned with government messaging while also providing genuine emotional sustenance to wartime audiences.

Why This Film Matters

The Life of Matsu the Untamed' holds significant cultural importance as one of the few Japanese films from the World War II era that successfully balanced artistic merit with the demands of wartime propaganda. The film's portrayal of a common person's dignity and moral strength became an important archetype in post-war Japanese cinema, influencing countless films about ordinary people facing extraordinary circumstances. The character of Matsugoro represented the ideal Japanese citizen - loyal, hardworking, and maintaining honor regardless of social status - themes that would continue to resonate in Japanese culture long after the war. The film's humanistic approach, focusing on personal relationships and individual dignity rather than overt nationalism, demonstrated how filmmakers could maintain artistic integrity even under oppressive political conditions. This work contributed to the development of the shomin-geki (genre focusing on common people) that would flourish in post-war Japanese cinema. The film also preserved important visual documentation of Tokyo's urban landscape before the extensive bombing of 1944-45, making it historically valuable beyond its artistic merits. Its success proved that audiences responded positively to stories emphasizing human connection and personal dignity, influencing the direction of Japanese cinema in the immediate post-war period.

Making Of

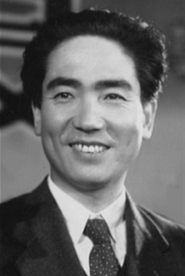

The production of 'The Life of Matsu the Untamed' took place under extraordinary circumstances during World War II. Director Hiroshi Inagaki, already an established filmmaker by 1943, had to work within the constraints of the Japanese Film Law, which gave the government extensive control over film content. Despite these pressures, Inagaki managed to create a film that emphasized humanistic values while subtly conforming to wartime expectations. The casting of Tsumasaburō Bandō, typically known for samurai roles, as a contemporary rickshaw driver was a deliberate choice to bridge traditional Japanese values with modern circumstances. The film's production team faced daily challenges including limited film stock, power restrictions, and the constant threat of air raids on Tokyo. Many scenes had to be filmed quickly and efficiently, with minimal takes due to resource constraints. The relationship between Matsugoro and young Toshio was developed through extensive rehearsal between Bandō and child actor Hiroyuki Nagato, creating a genuine on-screen chemistry that resonated with wartime audiences seeking messages of hope and human connection.

Visual Style

The cinematography, credited to Masao Tamai, employed a realistic style that captured the authentic atmosphere of Tokyo's working-class neighborhoods during the early 20th century period setting. The camera work emphasized natural lighting and location shooting to create a sense of immediacy and authenticity. Tamai used tracking shots to follow the rickshaw through city streets, creating dynamic movement that reflected Matsugoro's energetic spirit. The visual composition carefully balanced intimate character moments with broader social contexts, using depth of field to show the relationship between individuals and their community. Despite wartime restrictions on film stock, the cinematography maintained high visual quality, with careful attention to period details in costumes, props, and settings. The contrast between Matsugoro's humble world and his wealthy employers' environment was conveyed through subtle visual cues rather than dramatic differences, emphasizing shared humanity over class division.

Innovations

Despite the severe technical limitations of wartime production, the film achieved remarkable technical quality through innovative solutions to material shortages. The production team developed new methods for stretching limited film stock through careful planning and minimal retakes. Location filming in actual Tokyo neighborhoods required portable equipment modifications to work with the city's inconsistent power supply due to wartime rationing. The sound recording team created new techniques for capturing clear dialogue in noisy urban environments without modern soundproofing equipment. The film's editing, by Koichi Iwashita, maintained smooth narrative flow despite the constraints of limited coverage options. The production also pioneered methods for creating period atmosphere with minimal resources, using actual locations and props rather than expensive set construction. These technical adaptations demonstrated the Japanese film industry's ability to maintain quality standards under extreme wartime conditions.

Music

The musical score was composed by Seiichi Suzuki, who created a soundtrack that blended traditional Japanese musical elements with Western-influenced orchestral arrangements popular in Japanese cinema of the era. The main theme emphasized Matsugoro's indomitable spirit through uplifting melodic lines that recurred throughout the film. Suzuki incorporated traditional Japanese instruments like the shamisen and shakuhachi in scenes emphasizing cultural values, while using fuller orchestral arrangements for emotional moments. The soundtrack avoided the militaristic themes common in many wartime films, instead focusing on humanistic melodies that underscored the story's emotional core. Sound design emphasized the authentic sounds of rickshaws on city streets, creating an immersive urban atmosphere. The music effectively supported the film's narrative without overwhelming the performances, maintaining a delicate balance that enhanced rather than dictated emotional responses.

Famous Quotes

Even the lowest man can stand tall when he helps others who cannot help themselves.

A rickshaw carries not just people, but dreams and hopes to their destinations.

True wealth is not in what you own, but in whose lives you have touched.

In this world, it's not the strength of your arms that matters, but the strength of your heart.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Matsugoro joyfully navigates his rickshaw through Tokyo's busy streets, establishing his character's energy and connection to the city

- The pivotal moment when Matsugoro discovers the injured Toshio and immediately abandons his fare to help the child, demonstrating his selfless nature

- The emotional scene where Matsugoro teaches Toshio to ride the rickshaw, symbolizing the passing of wisdom between generations

- The climactic confrontation where Matsugoro defends his honor against prejudice, showing that dignity transcends social class

Did You Know?

- This film was one of the few Japanese productions from 1943 that focused on humanistic themes rather than overt wartime propaganda

- Tsumasaburō Bandō was one of Japan's most famous jidaigeki (period drama) actors, making this contemporary setting unusual for his career

- The film's release coincided with a period when the Japanese government was heavily controlling film content, yet it managed to emphasize individual human dignity

- Director Hiroshi Inagaki would later win an Academy Award for 'Rickshaw Man' (1958), which shares thematic similarities with this earlier work

- The rickshaw driver character became a recurring archetype in Japanese cinema, representing the dignity of common people

- Hiroyuki Nagato, who played the young boy Toshio, was only 8 years old during filming and would go on to have a distinguished career spanning six decades

- The film was shot on location in Tokyo neighborhoods that still retained their pre-war character, many of which would be destroyed by bombing raids the following year

- Keiko Sonoi, who played Toshio's mother, would die tragically in 1945 when the transport ship she was on was torpedoed by an American submarine

- The production had to obtain special permission from the military government to film urban scenes, as most resources were being diverted to war efforts

- The film's emphasis on class harmony and social unity reflected the government's wartime messaging, though approached through personal drama rather than direct propaganda

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics in 1943 praised the film for its heartfelt storytelling and Tsumasaburō Bandō's powerful performance, with Kinema Junpo specifically highlighting how the film managed to uplift spirits without resorting to overt propaganda. Critics noted that Inagaki's direction maintained a delicate balance between meeting wartime expectations and preserving artistic integrity. Post-war critics have reevaluated the film as an important example of how Japanese cinema maintained humanistic values during the war years. Modern film historians consider it a significant work that demonstrates the resilience of Japanese artistic expression under political pressure. The film is often cited in scholarly works about wartime Japanese cinema as an example of successful resistance through subtlety and emphasis on universal human values. Critics have also noted how the film's themes anticipate the humanistic focus that would dominate Japanese cinema in the 1950s golden age.

What Audiences Thought

The film was warmly received by Japanese audiences in 1943, who found emotional resonance in its story of human dignity and connection during increasingly difficult wartime conditions. Theater reports indicated that audiences responded particularly strongly to the relationship between Matsugoro and young Toshio, seeing in it a model of the ideal family bonds that wartime propaganda promoted. The film's success at the domestic box office (though exact figures are unavailable) led to extended runs in major cities. Audience letters and contemporary accounts suggest that viewers appreciated the film's optimistic tone and its portrayal of common people's strength and honor. The film became particularly popular in working-class neighborhoods where viewers identified with Matsugoro's struggles and values. In the years following the war, the film maintained a positive reputation among those who had seen it, remembered as one of the more meaningful works from the war years.

Awards & Recognition

- Kinema Junpo Award for Best Actor (Tsumasaburō Bandō, 1944)

- Mainichi Film Award for Best Film (1944)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Japanese literary tradition of commoner stories

- Contemporary Japanese social realist films

- Traditional Japanese values of loyalty and honor

- Hollywood humanist dramas of the 1930s

This Film Influenced

- Rickshaw Man (1958)

- Tokyo Story (1953)

- The Human Condition (1959)

- Early Spring (1956)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Japanese National Film Archive and has been partially restored. While the complete original negative no longer exists, high-quality prints from the 1940s have been digitized and preserved. Some minor deterioration is present in certain scenes, but the film remains largely intact and viewable. The restoration work was completed in 2008 as part of a broader effort to preserve Japanese wartime cinema.