The Man from Egypt

"Beware the ire of the sacred God Ammett!"

Plot

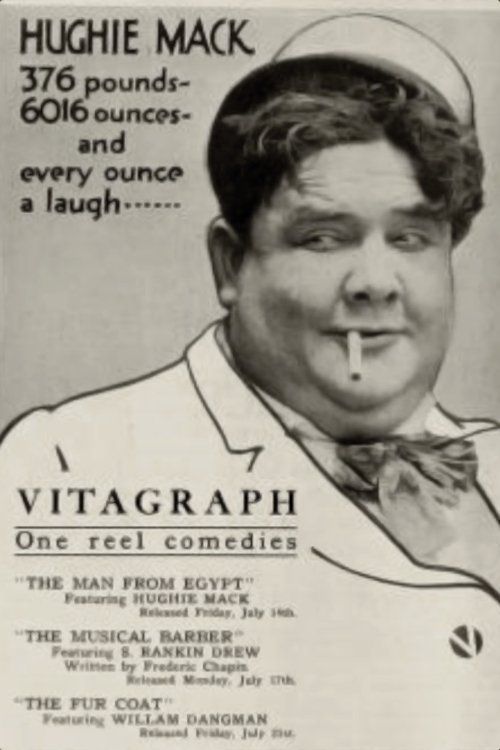

Hughie, a bellhop working at a hotel, comes into possession of a valuable ruby known as the Eye of Ammet, which he uses to gain entry into high society and meet a wealthy millionaire and his beautiful daughter. Unbeknownst to Hughie, the ruby was stolen from an Egyptian shrine, and a determined sheik has sworn to neither eat, drink, nor sleep until he recovers the sacred gem and exacts vengeance on the thief. Just as Hughie is enjoying a romantic dinner with the millionaire's daughter, the sheik discovers his whereabouts and initiates a frantic chase scene through various locations. After the sheik temporarily secures the ruby, Hughie cleverly retrieves it, leaving the vengeful sheik to continue his fasting vigil until he can recover the precious stone once more.

Director

About the Production

The Man from Egypt was produced during the height of the silent comedy era when Larry Semon was establishing himself as a prominent comedy director. The film capitalized on the contemporary fascination with Egyptology that had swept America following archaeological discoveries in Egypt. The production utilized elaborate sets designed to mimic Egyptian temples and opulent hotel interiors, typical of Vitagraph's commitment to visual spectacle in their comedy shorts.

Historical Background

The Man from Egypt was released in 1916, a pivotal year in world history as World War I raged in Europe while America remained neutral. In the film industry, 1916 marked the height of the silent film era, with comedies being among the most popular genres. The year also saw the release of D.W. Griffith's controversial masterpiece 'Intolerance,' which pushed the boundaries of cinematic art. The fascination with Egypt that permeated American culture during this period was fueled by recent archaeological discoveries and the opening of King Tutankhamun's tomb would soon captivate the world in 1922. This cultural zeitgeist made Egyptian-themed films particularly appealing to audiences of the time.

Why This Film Matters

The Man from Egypt represents a typical example of the short comedy format that dominated American cinema in the 1910s. As a Larry Semon production, it contributes to understanding the evolution of American comedy and Semon's influence on later comedians. The film also serves as a historical artifact reflecting the period's Egyptomania and Hollywood's often stereotypical portrayal of non-Western cultures. Its preservation helps document the transition from slapstick comedy's early days to more sophisticated comedic storytelling that would emerge in the 1920s.

Making Of

The production of The Man from Egypt took place during a transitional period in Hollywood when studios were moving from New York to California. Larry Semon, known for his energetic visual gags and elaborate chase sequences, incorporated his signature style into this Egyptian-themed comedy. The film's sets were designed to create the illusion of both Egyptian temples and luxurious hotel interiors, showcasing Vitagraph's commitment to production value even in short films. The chase sequences required extensive coordination between the actors and stunt performers, with Hughie Mack performing many of his own physical comedy stunts. The film was shot on the Vitagraph studio lot in Hollywood, which had recently been expanded to accommodate the growing demand for feature films and quality shorts.

Visual Style

The cinematography in The Man from Egypt was typical of Vitagraph productions in 1916, featuring relatively static camera positions with occasional tracking shots during chase sequences. The film used natural lighting for outdoor scenes and artificial lighting for interior sets, which was standard practice for the era. The Egyptian temple scenes employed dramatic lighting techniques to create mysterious atmospheres, while the hotel interiors were brightly lit to emphasize the comedy. The film's visual style prioritized clarity over artistic experimentation, ensuring that audiences could easily follow the physical gags and narrative action.

Innovations

The Man from Egypt employed standard filmmaking techniques for its era but demonstrated Vitagraph's commitment to production quality in their short comedies. The film's set design was more elaborate than typical comedy shorts of the period, featuring detailed Egyptian temple facades and well-appointed hotel interiors. The chase sequences required careful choreography and timing, showcasing the growing sophistication of action staging in silent comedies. The film also utilized cross-cutting techniques to build suspense during the pursuit scenes, a technique that was becoming increasingly sophisticated in 1916.

Music

As a silent film, The Man from Egypt would have been accompanied by live musical performances during its theatrical run. The typical score would have included popular songs of the period, classical pieces adapted for comedic effect, and original improvisations by theater musicians. The chase sequences likely featured fast-paced, lively music to enhance the action, while the romantic scenes would have been accompanied by more melodic, romantic themes. The Egyptian scenes probably incorporated 'exotic' sounding music to evoke the setting, possibly using instruments associated with Middle Eastern music.

Did You Know?

- Larry Semon, who directed this film, was one of the most prolific comedy directors of the silent era, directing over 100 films in his career

- The film was released during the peak of Egyptomania in America, a cultural fascination with ancient Egypt that influenced fashion, architecture, and popular culture

- Hughie Mack, the star, was a popular comedy actor who often played bumbling, good-hearted characters in silent comedies

- The Eye of Ammet was a fictional creation, but it drew inspiration from real Egyptian mythology and the concept of cursed artifacts

- This film is one of many silent comedies that used the 'stolen artifact' trope as a plot device to generate chase sequences and physical comedy

- Jewell Hunt, who played the millionaire's daughter, was a frequent collaborator with Larry Semon and appeared in many of his films

- The sheik character in the film was part of a broader Hollywood trend of stereotypical Middle Eastern characters in early cinema

- Vitagraph Company of America, the production company, was one of the pioneering film studios in early American cinema

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of The Man from Egypt were generally positive, with critics praising Hughie Mack's comedic timing and Larry Semon's energetic direction. The trade publication Moving Picture World noted the film's 'amusing situations' and 'well-executed chase sequences.' Modern critics, when the film is available for viewing, often analyze it within the context of early 20th-century comedy tropes and cultural representations. The film is typically regarded as a competent but not groundbreaking example of its genre and era.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1916 responded favorably to The Man from Egypt, as it provided the escapist entertainment that moviegoers sought during the tense period of World War I. The combination of physical comedy, exotic settings, and a straightforward plot made it accessible to a broad audience. The film's release as part of a program of shorts meant it was seen by a wide range of theater patrons, from working-class nickelodeon attendees to more sophisticated theater-goers.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier Keystone comedies

- Chaplin's tramp characterizations

- Egyptian-themed popular culture

- Slapstick traditions from vaudeville

This Film Influenced

- Later Larry Semon comedies

- 1920s chase comedies

- Other Egyptian-themed silent films