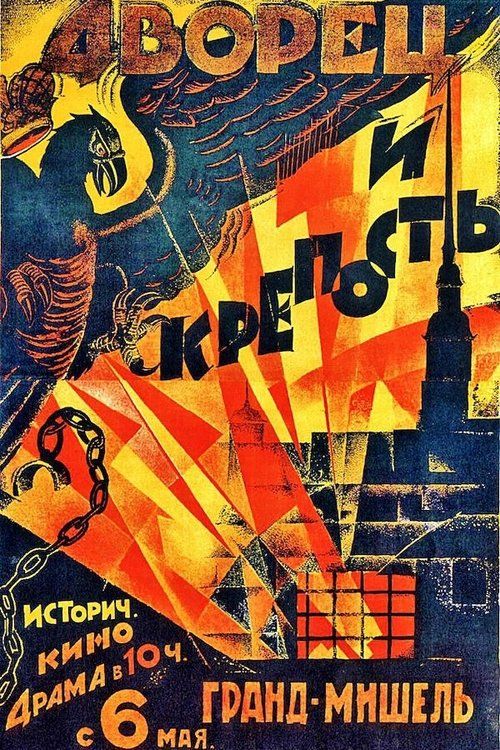

The Palace and the Fortress

Plot

The Palace and the Fortress tells the dramatic story of Mihail Beideman, a revolutionary figure in 19th century Russia, based on Olga Frosh's novel. The film contrasts the opulent world of the Russian aristocracy with the harsh conditions of political prisoners in the infamous Peter and Paul Fortress. Beideman's journey from idealistic revolutionary to imprisoned dissident forms the central narrative, highlighting the stark inequalities of Tsarist Russia. The story explores themes of political sacrifice, class struggle, and the personal costs of revolutionary fervor. Through its dual settings of palace and prison, the film creates a powerful visual metaphor for the social divisions that would eventually lead to the Russian Revolution.

About the Production

This film was produced during the early years of Soviet cinema when the industry was still establishing itself under state control. Director Aleksandr Ivanovsky was one of the pioneering figures of Soviet filmmaking, having started his career in the pre-revolutionary Russian film industry. The adaptation of Olga Frosh's novel reflects the Soviet government's interest in films that portrayed revolutionary heroes and criticized the Tsarist regime. The production likely faced significant challenges due to the economic difficulties of post-revolutionary Russia and the limited technical resources available to filmmakers at the time.

Historical Background

The Palace and the Fortress was produced in 1924, a crucial year in early Soviet history. This was during the New Economic Policy (NEP) period, which allowed for limited private enterprise and cultural experimentation. The Soviet film industry was still in its infancy, having been nationalized in 1919 and struggling with limited resources and technical expertise. 1924 also marked the death of Vladimir Lenin, leading to a power struggle that would eventually see Joseph Stalin rise to power. The film's focus on revolutionary heroes and criticism of the Tsarist regime aligned perfectly with the Soviet government's cultural policies of the time. This period saw the emergence of many pioneering Soviet directors who would later become internationally famous, though they were still developing their distinctive styles in 1924. The film industry was primarily focused on creating educational and propaganda content that would serve the new socialist state.

Why This Film Matters

The Palace and the Fortress represents an important example of early Soviet historical drama, a genre that would become central to Soviet cinema. The film's focus on revolutionary martyrs like Mihail Beideman helped establish the narrative framework for how Soviet cinema would portray the pre-revolutionary struggle. While the film itself may be lost, its existence demonstrates the early Soviet commitment to creating films that glorified revolutionary heroes and condemned the old regime. This approach would influence countless Soviet historical films throughout the 20th century. The film also illustrates the transition from pre-revolutionary Russian cinema to the distinctive Soviet cinematic language that would emerge later in the 1920s with directors like Eisenstein and Vertov. Its adaptation of contemporary Soviet literature shows the close relationship between the film industry and the broader cultural revolution taking place in the Soviet Union.

Making Of

The making of The Palace and the Fortress took place during a transformative period in Soviet cinema history. Director Aleksandr Ivanovsky brought his extensive experience from the pre-revolutionary Russian film industry to this production, adapting his techniques to serve the new ideological requirements of Soviet art. The film was likely shot on location in Leningrad, utilizing the authentic architecture of the former imperial capital. The production would have been constrained by the severe economic conditions of NEP-era Russia, with limited film stock, basic equipment, and often improvised lighting. The actors, primarily drawn from Leningrad's theatrical tradition, would have needed to adapt their stage acting styles for the more intimate medium of film. The production team faced the challenge of creating period-accurate depictions of 19th-century Russia while working with limited resources, often having to reuse costumes and props from other productions or repurpose items from the former imperial theaters.

Visual Style

While specific details about the cinematography of The Palace and the Fortress are not available due to the film's apparent loss, we can infer certain aspects based on early Soviet cinema practices of 1924. The cinematographer would likely have used natural lighting where possible, given the limited electrical resources available. The contrast between palace and prison settings would have provided opportunities for dramatic visual juxtaposition, with the palace scenes featuring elaborate compositions and the prison scenes using more claustrophobic framing. Camera movements would have been relatively simple, as complex tracking shots were technically difficult and expensive in this period. The film would have been shot on black and white film stock, with intertitles providing dialogue and narrative exposition. The visual style would have been influenced by both pre-revolutionary Russian cinema and emerging Soviet aesthetic principles, though the distinctive Soviet montage theory was still in development in 1924.

Innovations

The Palace and the Fortress was produced using the standard film technology available in the Soviet Union in 1924. The film would have been shot on 35mm film using hand-cranked cameras, resulting in variable frame rates that could range from 16 to 24 frames per second. Lighting would have relied heavily on natural light and basic artificial lighting equipment. The production would have faced significant technical challenges due to the limited resources available in post-revolutionary Russia, including shortages of film stock and equipment. While the film may not have introduced major technical innovations, it represents the ongoing development of Soviet cinema's technical capabilities during this period. The contrast between interior palace scenes and prison sequences would have required different lighting setups and camera techniques, demonstrating the growing sophistication of Soviet film production methods.

Music

As a silent film, The Palace and the Fortress would not have had a synchronized soundtrack, but it would have been accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical screenings. The typical practice in Soviet cinemas of the 1920s was to have a pianist or small orchestra provide musical accompaniment. The score would likely have included popular revolutionary songs, classical pieces appropriate to the historical setting, and improvised music to enhance the dramatic moments. The music would have been chosen to reinforce the ideological message of the film, with triumphant themes for revolutionary moments and somber music for scenes of oppression. Unfortunately, no specific information about the musical accompaniment for this particular film has survived. The experience of watching the film would have been significantly different from modern viewing, with the live music creating a communal theatrical atmosphere.

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic contrast scenes between the opulent palace balls and the stark prison cells of the Peter and Paul Fortress, visually representing the extreme social inequalities of Tsarist Russia

Did You Know?

- The film is based on the real-life story of Mihail Beideman, a Russian revolutionary who was imprisoned for his political activities in the 1860s

- Director Aleksandr Ivanovsky was one of the few directors who successfully transitioned from Tsarist-era cinema to Soviet filmmaking

- The source novel by Olga Frosh was part of a wave of revolutionary literature published in the early Soviet period

- 1924 was a pivotal year for Soviet cinema, marking the beginning of what would become the golden age of Soviet silent film

- The film's title reflects the dual focus on aristocratic privilege and revolutionary imprisonment

- Very little footage from this film is known to survive today, making it one of the many lost treasures of early Soviet cinema

- The cast were primarily stage actors from Leningrad theaters, as was common in early Soviet films

- The Peter and Paul Fortress depicted in the film was a real prison that housed many famous revolutionaries

- The film was produced by Goskino, the state film organization that controlled all Soviet film production

- 1924 saw the death of Lenin, which significantly impacted the cultural landscape of the Soviet Union

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of The Palace and the Fortress is difficult to ascertain due to the scarcity of surviving documentation from this period. Early Soviet film criticism was primarily concerned with ideological correctness rather than artistic merit, and reviewers would have evaluated the film based on how well it served the revolutionary cause. The film's focus on a historical revolutionary figure would likely have been praised for its educational value and ideological clarity. Soviet critics of the 1920s were also interested in the technical aspects of filmmaking, so the film's visual representation of the contrast between palace and prison would have been noted. Modern critical assessment is impossible due to the apparent loss of the film, though film historians recognize it as part of the important body of early Soviet historical dramas that laid the groundwork for later masterpieces.

What Audiences Thought

Information about audience reception to The Palace and the Fortress is not available in surviving records. In the early 1920s, Soviet audiences were still developing literacy in the language of cinema, and their tastes were being shaped by the limited selection of films available. The film's historical subject matter and revolutionary themes would likely have resonated with audiences who had recently lived through the revolution and civil war. However, many Soviet citizens in 1924 were still more familiar with pre-revolutionary films, and the new Soviet cinema was competing with imported films for audience attention. The lack of detailed audience reception data reflects the broader challenge of studying early Soviet cinema, where many records have been lost or were never systematically collected.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Pre-revolutionary Russian historical dramas

- Contemporary Soviet revolutionary literature

- The theatrical tradition of Leningrad stages

- Early Soviet propaganda films

- The works of pre-revolutionary Russian directors like Yevgeni Bauer

This Film Influenced

- Later Soviet historical dramas about revolutionary heroes

- Films depicting the Tsarist prison system

- Soviet films exploring class conflict themes

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Palace and the Fortress is considered a lost film. Like many Soviet films from the early 1920s, no complete copies are known to exist in any film archive. This loss reflects the broader tragedy of early Soviet cinema, where many films were destroyed due to neglect, improper storage conditions, or deliberate destruction during various political purges. Some fragments or still photographs may exist in Russian film archives, but the complete film is not available for viewing. The loss of this film is particularly significant as it represents an early example of Soviet historical drama and the work of director Aleksandr Ivanovsky during his transition period from pre-revolutionary to Soviet cinema.