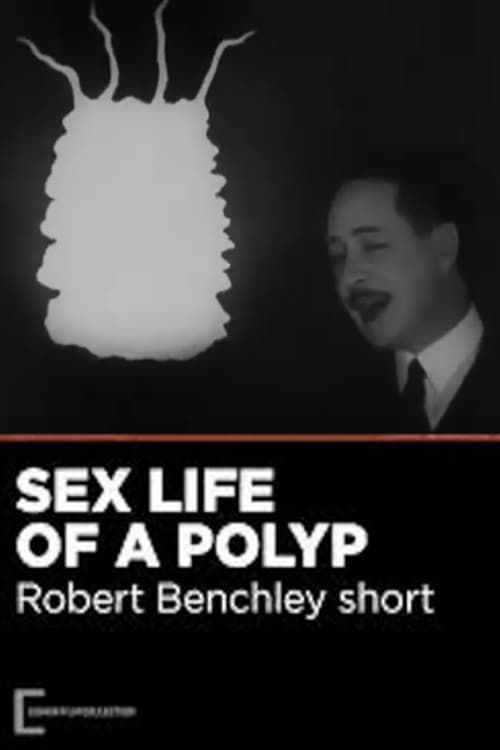

The Sex Life of the Polyp

Plot

Dr. Robert Benchley delivers a mock scientific lecture to a Ladies Club about the reproductive habits of polyps, small aquatic organisms. Despite being unable to display his live specimens, he presents a series of photographs documenting his research. Benchley explains that the study is complicated by the polyps' ability to change sex periodically, leading to humorous confusion and misunderstanding. As he presents his pictures and describes his experiments, his comically inadequate scientific knowledge and increasingly flustered demeanor create mounting absurdity. The lecture culminates in Benchley's complete loss of composure as he struggles to explain the complex biological concepts to his bewildered audience.

Director

Cast

About the Production

This was one of Robert Benchley's earliest film appearances, capturing his signature lecture style that would later become famous in his 'How to...' series. The film was shot as a silent short but was later synchronized with music and sound effects. Benchley's performance was largely improvised, building on his popular stage routine of mock academic lectures.

Historical Background

The Sex Life of the Polyp was produced during the transition from silent films to talkies in 1928, a period of tremendous technological and artistic upheaval in Hollywood. This film represents an early example of the sound short format that studios were experimenting with as they adapted to the new technology. The late 1920s also saw the rise of sophisticated comedy in American cinema, moving away from slapstick toward more verbal and situational humor. Benchley's intellectual, deadpan comedy style reflected the growing sophistication of American audiences and the influence of the Algonquin Round Table, of which Benchley was a prominent member.

Why This Film Matters

This film marked the beginning of Robert Benchley's influential film career, establishing the template for the comedic lecture format that he would perfect in later shorts like 'The Treasurer's Report' and his 'How to...' series. Benchley's style of intellectual comedy, which poked fun at academic pretension while celebrating human fallibility, would influence generations of comedists from Woody Allen to Stephen Colbert. The film also represents an early example of the mockumentary format, predating what would become a popular comedy genre by decades.

Making Of

The production was a relatively simple affair, shot in just two days at Fox's New York studios. Benchley, who was nervous about performing for the camera, insisted on multiple takes to perfect his timing. The director, Thomas Chalmers, gave Benchley considerable freedom to improvise, recognizing that his comedic strength lay in his natural delivery and timing. The film's minimal set design consisted of a simple lectern and backdrop, allowing Benchley's performance to be the sole focus. The sound synchronization was added in post-production, with Benchley re-recording his dialogue to match the filmed performance.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Joseph H. August was straightforward and functional, typical of early sound shorts that prioritized clear audio recording over visual experimentation. The camera remains largely static, focusing on Benchley at his lectern, with occasional cuts to show the audience's reactions. The lighting is bright and even, ensuring Benchley's facial expressions and gestures are clearly visible. This simple approach effectively serves the comedy by keeping the focus squarely on Benchley's performance without visual distractions.

Innovations

The film represents an early successful example of sound synchronization in comedy, demonstrating how verbal humor could be effectively captured in the new medium. The production team managed to overcome the technical challenges of recording clear dialogue while maintaining comedic timing. The film also shows early experimentation with the relationship between sound and image in comedy, using audio cues to enhance visual gags. These technical achievements, while modest by later standards, were significant for 1928 and helped pave the way for more sophisticated sound comedies.

Music

As an early sound film, the soundtrack was rudimentary but innovative for its time. The film featured synchronized music and sound effects, with Benchley's voice recorded using early sound-on-film technology. The musical accompaniment consisted of light, jaunty piano pieces that underscored the comedic moments. Sound effects were minimal but effective, including the rustling of papers and the occasional cough from the audience. The audio quality reflects the limitations of 1928 recording technology but captures Benchley's distinctive vocal delivery with reasonable clarity.

Famous Quotes

The polyp, as you may or may not know, is a small aquatic organism of great scientific interest and even greater confusion.

You see, the trouble with studying polyps is that they have this unfortunate habit of changing their sex from time to time, which makes my research rather complicated and my wife rather suspicious.

I have here a series of photographs of my subjects, though I must warn you that polyps are not particularly photogenic and tend to look rather like small, wet, and somewhat disagreeable vegetables.

The reproductive habits of the polyp are, to put it mildly, complicated. To put it frankly, they're confusing. To put it honestly, I haven't the faintest idea what they're doing.

As you can see from this next picture, the polyp has now decided to become a female, which I personally think is rather inconsiderate of it, as I had just gotten used to calling him 'he'.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening scene where Benchley nervously adjusts his glasses and papers before beginning his lecture to the attentive Ladies Club, establishing his flustered academic persona

- The moment when Benchley attempts to explain polyp sex changes while becoming increasingly embarrassed, his voice cracking as he struggles to maintain scientific composure

- The sequence where Benchley presents his 'photographs' of polyps, holding up blank pieces of paper and describing increasingly absurd images that only he can see

- The climax where Benchley completely loses his train of thought, mixing up his scientific terms and accidentally revealing his ignorance about the subject while the audience looks on in confusion

Did You Know?

- This was Robert Benchley's film debut, marking his transition from stage and print to cinema

- The film was based on Benchley's popular stage routine that he had been performing for years

- Director Thomas Chalmers was primarily known as a stage director and opera singer

- The polyp specimens mentioned in the film were entirely fictional, created for comedic effect

- This short film was part of Fox's early experiments with sound synchronization

- Benchley's flustered academic persona in this film would become his trademark throughout his career

- The Ladies Club audience was played by actual New York socialites, not professional actresses

- The film was considered quite risqué for its time due to its subject matter, despite being presented in a scientific context

- Only one print of the film is known to survive, preserved at the Museum of Modern Art

- Benchley later claimed he knew nothing about polyps and made up all the 'scientific' information on the spot

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Benchley's performance as refreshingly sophisticated and noted his natural transition from stage to screen. Variety called it 'a delightful bit of sophisticated humor' and predicted great things for Benchley in cinema. Modern critics view the film as an important historical document showcasing the birth of a unique comedic voice. Film historians consider it a crucial link between Benchley's literary career and his later Hollywood success, demonstrating how his distinctive humor translated to the new medium of sound film.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1928 responded positively to Benchley's urbane wit, finding his flustered professor persona both relatable and hilarious. The film was particularly popular with urban, educated viewers who appreciated its intellectual humor. While not a blockbuster, the short performed well enough to convince Fox and other studios of Benchley's potential as a film personality. Modern audiences who have seen the film through archival screenings and film festivals continue to appreciate its timeless humor and Benchley's masterful comic timing.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Benchley's Algonquin Round Table wit

- Mark Twain's humorous essays

- Stage comedy traditions

- Vaudeville monologues

This Film Influenced

- The Treasurer's Report (1930)

- How to Sleep (1935)

- The Early Bird (1936)

- A Night at the Opera (1935)

- Bringing Up Baby (1938)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and has been restored by the UCLA Film and Television Archive. While not considered lost, it remains relatively rare with only one known complete print existing. The restoration has preserved both the visual elements and the early soundtrack, maintaining the film's historical and artistic integrity.