The Young Lady and the Hooligan

Plot

A young, idealistic schoolteacher arrives at her first teaching assignment, tasked with educating a class of illiterate adult males ranging from young boys to elderly men. The classroom environment proves challenging as her students are rowdy, disruptive, and resistant to learning. The situation intensifies when a young hooligan boldly declares his love for her by writing it on his test paper, creating tension and discomfort. While other students initially defend the teacher against what they perceive as harassment, she begins to sense the sincerity behind the young man's raw emotions. The story culminates tragically when the hooligan is stabbed by his fellow students, and as he lies dying, the teacher acknowledges his genuine feelings by comforting him with a tender kiss.

Director

Yevgeni SlavinskyAbout the Production

Filmed during the tumultuous period of the Russian Civil War, the production faced numerous challenges including limited resources, film shortages, and political instability. The film was shot on location in Moscow during 1918, a time when the city was experiencing severe food shortages and political upheaval. Director Yevgeni Slavinsky had to work with extremely limited film stock and equipment, often having to reuse and recycle materials. The production was one of the first to continue operating after the Bolshevik Revolution, navigating the new Soviet film policies.

Historical Background

The film was produced in 1918, a pivotal year in Russian history that saw the country deeply embroiled in the aftermath of the Bolshevik Revolution and the brutal Russian Civil War. This period marked the transformation of the Russian film industry from a primarily commercial enterprise to a tool of political education and propaganda under the new Soviet regime. The film's themes of education, social transformation, and the relationship between the intellectual class and the working masses reflected the new Soviet priorities of creating an educated proletariat. The year 1918 also saw the nationalization of the Russian film industry, with the Bolshevik government establishing the People's Commissariat for Education to oversee cultural production. The film's production occurred during the brief window when private film companies like Neptun could still operate before complete nationalization took effect. The story's focus on literacy education was particularly relevant, as the new Soviet government launched massive literacy campaigns to combat the widespread illiteracy that had characterized Tsarist Russia.

Why This Film Matters

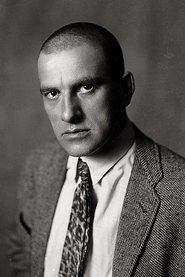

This film holds a unique place in Russian cinematic history as one of the earliest surviving examples of post-revolutionary Russian cinema and as the only starring vehicle for Vladimir Mayakovsky, one of Russia's most influential 20th-century poets. The film represents the intersection of poetry, visual art, and revolutionary politics that characterized the Russian avant-garde movement. Mayakovsky's involvement demonstrated the fluid boundaries between artistic disciplines during this period, as many writers and visual artists experimented with the new medium of cinema. The film's exploration of themes like education, class dynamics, and romantic passion against a backdrop of social upheaval anticipated many concerns that would dominate Soviet cinema in the following decades. Its survival, though incomplete, provides valuable insight into the aesthetic and ideological concerns of early Soviet filmmakers as they worked to define a new revolutionary cinema that would serve both artistic and political purposes. The film also serves as an important document of Mayakovsky's artistic output beyond poetry, showing his engagement with multiple media forms.

Making Of

The production of 'The Young Lady and the Hooligan' took place under extraordinary circumstances during one of the most turbulent periods in Russian history. The film was shot in Moscow in 1918, while the city was besieged by various political factions and experiencing severe shortages of food, electricity, and basic supplies. Director Yevgeni Slavinsky had to navigate not only the technical challenges of filmmaking during wartime but also the rapidly changing political landscape as the Bolsheviks consolidated power. Vladimir Mayakovsky, though primarily known as a poet, brought his revolutionary artistic sensibility to the project, writing the scenario and delivering a performance that embodied the raw, passionate energy of the futurist movement. The cast and crew often worked in unheated studios during the harsh Russian winter, and film stock was so precious that multiple takes were rarely possible. Despite these hardships, the production team managed to create a film that captured the social and emotional tensions of the revolutionary era, with Mayakovsky's intense performance becoming particularly memorable for its authenticity and emotional power.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'The Young Lady and the Hooligan' reflects the transitional nature of Russian cinema in 1918, incorporating techniques from both the late Tsarist period and the emerging Soviet aesthetic. The film uses relatively static camera positions typical of the era but incorporates some innovative close-ups, particularly in scenes featuring Mayakovsky's expressive performance. The lighting design creates dramatic contrasts between the classroom setting and the more intimate emotional moments, using natural light when possible due to electricity shortages. The visual composition emphasizes the social tensions between the educated teacher and her working-class students through careful staging and character positioning. The film's visual style also incorporates some futurist influences through its dynamic framing of Mayakovsky's movements and its emphasis on physical expression. Despite the technical limitations of wartime production, the cinematography manages to convey both the social realism of the classroom scenes and the emotional intensity of the romantic drama.

Innovations

While not technically groundbreaking compared to some contemporary European productions, 'The Young Lady and the Hooligan' demonstrated notable technical achievements considering the extreme production constraints of 1918 Russia. The film's successful completion under wartime conditions, with limited film stock and resources, represented a significant logistical achievement. The production team developed innovative solutions for lighting and camera operation during frequent power outages and supply shortages. The film's editing techniques, while relatively simple by modern standards, effectively conveyed the emotional arc of the story through careful shot selection and pacing. The use of location shooting in Moscow, despite the city's dangerous conditions, added authenticity to the production. The film's preservation of Mayakovsky's performance, captured despite the technical limitations of the era, represents an important achievement in documenting one of Russia's major artistic figures. The surviving footage demonstrates the cinematographer's skill in capturing subtle emotional expressions and group dynamics within the constraints of early cinema technology.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Young Lady and the Hooligan' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical practice in Russian cinemas of 1918 involved a pianist or small orchestra providing improvised or compiled musical accompaniment that matched the mood of each scene. While no original score documentation survives for this specific film, contemporary accounts suggest that the musical accompaniment would have emphasized the dramatic tension between the classroom scenes and the romantic elements. The music likely incorporated popular Russian songs of the period along with classical pieces that could be quickly adapted to fit the on-screen action. In modern screenings, the film has been accompanied by various musical interpretations, from traditional piano scores to more experimental electronic compositions that reflect Mayakovsky's futurist aesthetic. The absence of synchronized sound allowed the visual performance, particularly Mayakovsky's intense physical acting, to carry the emotional weight of the story.

Famous Quotes

Written on test paper: 'I love you' - The hooligan's bold declaration

Dialogue intertitles expressing the teacher's internal conflict between professional duty and personal feelings

Final scene intertitle: 'In death, truth reveals itself'

Memorable Scenes

- The classroom chaos where the hooligan first declares his love on paper, creating tension among the students and discomfort for the teacher

- The confrontation scene where other students defend the teacher against the hooligan's advances, showing the complex social dynamics

- The deathbed scene where the teacher tenderly kisses the dying hooligan, acknowledging his genuine love and providing emotional closure

Did You Know?

- This film marked the only starring role for legendary Russian poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, who was primarily known for his revolutionary poetry and futurist art rather than acting.

- Mayakovsky wrote the scenario for the film himself, adapting it from a story by American writer Jack London, demonstrating his versatility across artistic mediums.

- The film was produced by the Neptun Film Company, which was one of the few private film companies allowed to operate briefly after the Bolshevik Revolution before being nationalized.

- Vladimir Mayakovsky's distinctive physical appearance - his tall stature and intense gaze - made him an unconventional but compelling screen presence in the role of the hooligan.

- The film was shot during the height of the Russian Civil War, making it one of the rare cinematic productions from this extremely turbulent period in Russian history.

- Director Yevgeni Slavinsky was a pioneering figure in early Russian cinema who later became an important director in the Soviet film industry.

- The film's theme of education and social transformation aligned with early Soviet ideals about creating a new, educated proletariat society.

- Only incomplete prints of the film survive today, with some scenes missing or damaged, making it a rare example of early Soviet cinema.

- The film's romantic elements were considered somewhat daring for the time, especially the final scene where the teacher kisses the dying hooligan.

- Mayakovsky's involvement in cinema was part of the broader futurist movement's embrace of new artistic forms and technologies.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of the film was limited due to the chaotic circumstances of 1918 Russia, with many newspapers and periodicals either ceasing publication or focusing exclusively on war coverage. However, the few reviews that did appear noted the novelty of seeing the famous poet Vladimir Mayakovsky on screen and praised his intense, authentic performance. Critics of the time commented on the film's bold thematic choices and its alignment with revolutionary ideals. Later Soviet film historians and critics have reassessed the film as an important transitional work between pre-revolutionary Russian cinema and the emerging Soviet film aesthetic. Modern scholars have particularly noted the film's significance as a document of Mayakovsky's artistic practice and its value in understanding the cultural politics of the early revolutionary period. The film is now recognized as an important artifact of early Soviet cinema, despite its incomplete preservation status.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception in 1918 is difficult to document precisely due to the lack of systematic box office tracking and the disruption of normal cultural life during the Civil War. However, contemporary accounts suggest that the film attracted significant attention due to Mayakovsky's participation, as his poetry readings had already made him a celebrity among Moscow's intellectual and artistic circles. The film's themes of education and social transformation resonated with many viewers who were experiencing the profound changes brought by the revolution. The romantic elements, particularly the controversial final scene, generated discussion among audiences about the changing moral and social codes in revolutionary Russia. In subsequent years, the film developed a cult following among Mayakovsky enthusiasts and scholars of early Soviet cinema. Today, the film is primarily viewed by academic audiences and cinema historians, though screenings at film festivals and retrospectives continue to attract interest from those curious about this unique collaboration between one of Russia's greatest poets and early cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Jack London's stories

- Russian realist literature

- Futurist artistic movement

- Early Soviet educational ideals

- Pre-revolutionary Russian melodrama

This Film Influenced

- Bed and Sofa (1927)

- The End of St. Petersburg (1927)

- Man with a Movie Camera (1929)

- Early Soviet educational films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in an incomplete and partially damaged condition, with some scenes missing or deteriorated. Portions of the original nitrate film stock have been preserved through archival restoration efforts, but the complete original version no longer exists. The surviving footage has been digitized and is held in Russian film archives, particularly the Gosfilmofond archive. Restoration work has been ongoing to preserve what remains of this historically significant film. The incomplete nature of the surviving print makes it a rare example of early Soviet cinema that has managed to survive the ravages of time and the political upheavals of the 20th century.