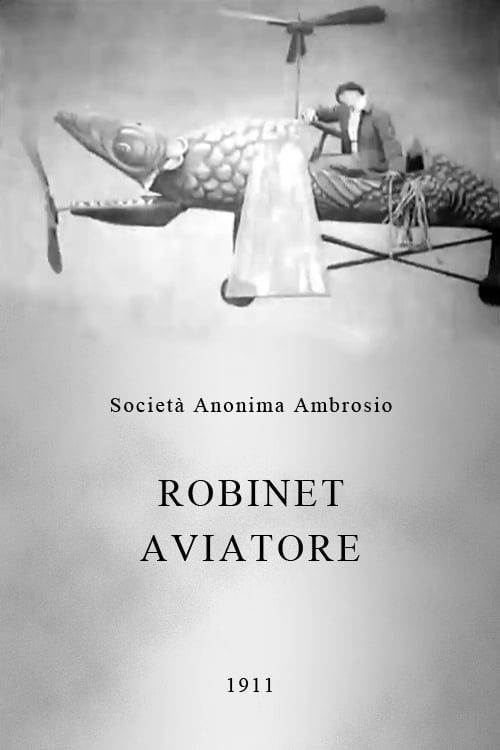

Tweedledum as Aviator

Plot

In this Italian slapstick comedy, the bumbling character Robinet becomes obsessed with the new and exciting world of aviation, desperately wanting to become an aviator despite having absolutely no aptitude for it. Robinet's attempts at flight involve increasingly disastrous and physically demanding mishaps as he tries to build his own flying machine or hijack existing ones. The film showcases the character's relentless determination and complete lack of common sense as he endures countless falls, crashes, and humiliations in pursuit of his aerial dreams. True to the bone-breaking style of Italian slapstick of the era, Robinet suffers spectacular physical comedy that makes even the famous Keystone comedies look tame by comparison. The film culminates in a chaotic finale where Robinet's aviation ambitions lead to maximum destruction and minimum success.

Director

Cast

About the Production

This film was produced during the golden age of Italian cinema when Turin was a major production center. The physical comedy was performed without stunt doubles or safety equipment, making the dangerous falls and crashes authentic to the performers' actual risk. The aviation theme capitalized on the public's fascination with flight following the Wright brothers' achievements and early aviation pioneers.

Historical Background

1911 was a pivotal year in cinema history, occurring during the transition from short novelty films to more sophisticated narrative storytelling. The film industry was rapidly expanding globally, with Italy emerging as a major cinematic power alongside France and the United States. This period saw the rise of national film industries and the development of genre conventions. Aviation was capturing the public imagination worldwide, with pioneers like Louis Blériot making headline-grabbing flights across the English Channel in 1909. The film was produced during the Italo-Turkish War (1911-1912), when Italy was asserting itself as a modern industrial and military power. Cinema was also becoming more respectable as an art form, moving from fairground attractions to dedicated theaters. The physically demanding style of Italian comedy reflected broader cultural values of bravado and spectacle that characterized Italian cinema of the period.

Why This Film Matters

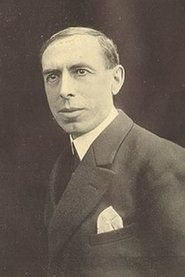

This film represents an important example of early Italian comedy and the international appeal of slapstick humor in the silent era. It demonstrates how cinema quickly adapted to contemporary obsessions, in this case the mania for aviation that swept the world in the early 1910s. The Robinet character, as portrayed by Marcel Perez, contributed to the development of the recurring comic protagonist archetype that would become central to film comedy. The film's extreme physical comedy style influenced subsequent slapstick traditions, even as it was eventually overshadowed by American comedies from Keystone and Mack Sennett. It also illustrates the global nature of early cinema, where Italian productions could find international audiences despite language barriers, relying on universal visual humor. The preservation of such films provides crucial insight into early 20th century popular culture and the evolution of cinematic comedy as an art form.

Making Of

The production of 'Tweedledum as Aviator' exemplified the rough-and-tumble approach to filmmaking in early Italian cinema. Unlike later productions with elaborate safety measures, Marcel Perez performed his own stunts, enduring real falls and physical impacts that would be considered unacceptable by modern standards. The film was likely shot quickly in one or two days, as was typical for short comedies of the era. The makeshift aviation equipment shown in the film was probably constructed by the studio's prop department using whatever materials were available, reflecting both the ingenuity and limitations of early film production. Director Luigi Maggi, coming from a theatrical background, would have staged the physical comedy to play well to live audiences, emphasizing broad gestures and visible impacts that would read clearly on screen without the benefit of sound.

Visual Style

The cinematography would have been characteristic of 1911 Italian filmmaking, using stationary cameras positioned to capture the full range of physical action. The camera would have been placed at a distance to ensure all of Robinet's movements and falls were visible within the frame. The film was likely shot in black and white on 35mm film, with outdoor scenes utilizing natural light. The composition would emphasize clarity of action over artistic framing, ensuring that the slapstick gags were easily understood by audiences. Long takes would have been preferred to maintain the continuity of physical comedy sequences. The aviation scenes would have required careful positioning to capture both the performer and any flying apparatus or props.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking in technical terms, the film demonstrates the sophisticated stunt coordination and physical comedy techniques being developed in Italian cinema. The aviation props and effects, while rudimentary by modern standards, showed creative problem-solving in depicting flight on screen. The film's success in capturing complex physical action in long takes required careful choreography and timing. The production likely utilized the relatively stable cameras and reliable film stock that had become available by 1911, allowing for greater freedom in shooting physical comedy. The film represents the refinement of slapstick techniques that would influence comedy filmmaking for decades.

Music

As a silent film, 'Tweedledum as Aviator' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical exhibition. The accompaniment could range from a single pianist to a small orchestra depending on the theater's resources. The music would have been selected to match the on-screen action, with lively, comedic themes for Robinet's antics and more dramatic or suspenseful music for the aviation sequences. Popular songs of the era might have been incorporated when relevant to the action. The score would have been improvised or drawn from published collections of photoplay music specifically compiled for silent film accompaniment. The absence of recorded sound meant that the visual comedy had to carry the entire narrative weight.

Memorable Scenes

- Robinet's disastrous attempt to construct and fly a makeshift airplane, resulting in a spectacular crash sequence typical of the era's dangerous stunt work

Did You Know?

- Marcel Perez, who played Robinet, was one of the most popular comic actors in early Italian cinema, creating the Robinet character that appeared in numerous shorts.

- The film was made just 8 years after the Wright brothers' first flight, capturing the public's intense fascination with aviation during its pioneering days.

- Italian slapstick comedies of this period were known for being exceptionally physical and dangerous, often involving real falls and crashes without the use of stunt performers.

- Director Luigi Maggi was not only a filmmaker but also an actor who had previously worked in theater before transitioning to cinema.

- The character name 'Robinet' was the Italian equivalent of characters like 'Max' in German cinema or 'Fatty' in American comedies - a recurring comic persona.

- Many of these early Italian comedies were exported internationally, with Robinet films being particularly popular in France and other European countries.

- The film was likely shot on location in Turin, which was home to Itala Film, one of Italy's most important early production companies.

- The aviation props and makeshift flying machines in the film would have been constructed specifically for the production, reflecting the experimental nature of early aircraft design.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of short comedies like 'Tweedledum as Aviator' was minimal, as film criticism as we know it today had not yet developed. Trade publications of the era would have focused more on the film's commercial potential and technical aspects rather than artistic merit. The film was likely reviewed in trade journals for its entertainment value and suitability for various programming slots. Modern film historians and archivists recognize such films as important cultural artifacts that provide insight into early cinematic comedy styles and the international nature of silent film production. The extreme physical comedy has been noted by scholars as characteristic of Italian slapstick's particularly brutal approach compared to other national traditions.

What Audiences Thought

Early audiences responded enthusiastically to the film's physical comedy and aviation theme, which tapped into contemporary interests in technological progress and human flight. The Robinet character was already established as a popular comic figure, so audiences would have been familiar with and receptive to his misadventures. The spectacular falls and crashes would have been major attractions, as early cinema audiences were thrilled by dangerous stunts and physical comedy. The film likely performed well in both domestic Italian markets and internationally, as slapstick comedy transcended language barriers. The aviation theme would have been particularly timely and exciting for audiences witnessing the rapid development of real-world aviation. The short format and straightforward humor made it ideal for the varied programming of early cinema theaters, which typically presented multiple short films per showing.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Early French comedies

- Commedia dell'arte traditions

- Contemporary aviation news

- Physical theater traditions

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent Robinet films

- Italian slapstick comedies

- Early aviation comedies

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of this specific 1911 film is unclear, as many early Italian comedies from this period have been lost or exist only in fragmentary form. Some Robinet films have survived in film archives, particularly in European collections, but the complete version of 'Tweedledum as Aviator' may be lost or partially preserved. Early nitrate film was highly flammable and prone to deterioration, making survival of films from this period rare.