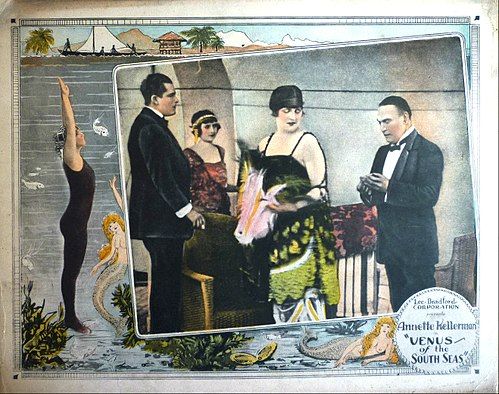

Venus of the South Seas

"A Romance of the Coral Seas"

Plot

In the exotic South Seas, Shona, the beautiful daughter of a pearl merchant, falls deeply in love with Julian, a wealthy traveler who has come to the region. When Shona's father unexpectedly dies, she inherits the family's lucrative pearl business, becoming one of the few women in the region to control such an enterprise. The greedy Captain Hammond, who has long coveted the pearl business, schemes to take control from Shona by exploiting her inexperience and the patriarchal attitudes of the local community. Shona must navigate treacherous waters both literally and figuratively as she fights to maintain her father's legacy while protecting her relationship with Julian, whose wealthy background makes him both an ally and a target of Hammond's manipulations. The film culminates in a dramatic confrontation where Shona uses her knowledge of the sea and pearl diving to outwit the villainous captain, proving that a woman can successfully run a business in a male-dominated world.

About the Production

The film was notable for its extensive underwater photography, which was highly innovative for 1924. Annette Kellerman, a professional swimmer and diving champion, performed her own underwater stunts and swimming sequences. The production faced challenges shooting underwater scenes with the limited technology available at the time, requiring custom waterproof camera housing and careful lighting arrangements. The tropical setting was recreated using a combination of location shooting in Bermuda and studio work at Universal's facilities.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the golden age of Hollywood silent cinema in 1924, a period when American film studios were expanding their global reach and exploring exotic locations to satisfy audience demand for adventure and romance. The 1920s saw a fascination with tropical settings and 'primitive' cultures, reflecting both post-WWI escapism and growing American interest in international travel. The film also emerged during a period of changing attitudes toward women's roles in society, with the women's suffrage movement having recently achieved success with the 19th Amendment in 1920. Annette Kellerman herself represented a new type of female star - athletic, independent, and unafraid to challenge conventional notions of femininity. The film's emphasis on underwater photography also reflected the technological optimism of the 1920s, when filmmakers were constantly pushing the boundaries of what was possible with camera technology and special effects.

Why This Film Matters

'Venus of the South Seas' holds significance as an early example of underwater cinematography in narrative cinema, predating more famous underwater films like '20,000 Leagues Under the Sea' (1954). The film also represents an important chapter in the career of Annette Kellerman, who was not only a film star but also a pioneer in women's athletics and fashion. Her performances helped normalize athletic bodies for women on screen and challenged restrictive notions of female propriety. The film's portrayal of a woman successfully running a business in a male-dominated environment, while still maintaining her femininity and romantic appeal, reflected changing attitudes about women's capabilities in the 1920s. Additionally, the film contributed to the popularization of South Pacific settings in American cinema, establishing visual and narrative tropes that would be reused in countless subsequent films.

Making Of

The production of 'Venus of the South Seas' was particularly challenging due to its ambitious underwater sequences. The film's crew had to develop custom waterproof camera housings, as commercial underwater camera equipment was not readily available in 1924. Annette Kellerman, leveraging her background as a professional swimmer, served as an informal consultant on the underwater scenes, helping to choreograph the swimming and diving sequences. The production team built large tanks at Universal Studios to simulate the South Seas environment, complete with artificial coral and marine life. Some scenes were filmed on location in Bermuda to capture authentic underwater footage, though the logistics were difficult and expensive. The film's pearl diving sequences required careful coordination between the camera crew and performers, as communication underwater was impossible with the technology of the time. Kellerman's swimming prowess allowed for longer takes underwater than would have been possible with most actresses of the era, contributing to the film's impressive underwater sequences.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'Venus of the South Seas' was groundbreaking for its time, particularly in the underwater sequences. The film utilized custom-built waterproof camera housings that allowed for filming beneath the water's surface, a technical feat that required significant innovation. The underwater scenes employed natural lighting where possible, supplemented by specially designed underwater lighting rigs that could be operated safely. The cinematography contrasted the vibrant, sunlit surface scenes with the mysterious, blue-tinted underwater world, creating a visual dichotomy that reinforced the film's themes. Above-water sequences used the standard techniques of the era, but the underwater photography employed slower camera movements to capture the graceful swimming sequences and the weightless quality of underwater movement. The film also featured early examples of split-screen techniques to show simultaneous above and below water action.

Innovations

The film's most significant technical achievement was its pioneering underwater cinematography, which required the development of waterproof camera equipment not commercially available in 1924. The production team created custom housing for cameras that could withstand water pressure while maintaining focus and exposure controls. The lighting systems for underwater scenes were particularly innovative, using a combination of surface lighting and underwater lamps to achieve adequate visibility. The film also featured early examples of underwater stunt coordination, with Annette Kellerman performing complex swimming sequences that required precise timing with the camera movements. The pearl diving sequences demonstrated advanced techniques for showing underwater action, including bubble effects and the simulation of depth changes. These technical innovations influenced subsequent underwater filming and contributed to the development of underwater cinematography as a specialized field.

Music

As a silent film, 'Venus of the South Seas' would have been accompanied by live musical performances during its original theatrical run. The score likely consisted of popular classical pieces and original compositions typical of the period, with exotic-sounding themes for the South Seas setting and romantic motifs for the love story. Universal Pictures often provided theaters with suggested musical cues and sheet music for their films. Some later re-releases of the film in the late 1920s featured synchronized sound effects and music using early sound-on-disc technology. The underwater sequences would have been particularly challenging to score effectively, requiring music that could convey both the beauty and danger of the underwater world without dialogue.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, dialogue was conveyed through intertitles. Key intertitles included: 'In the vast expanse of the South Seas, where pearls sleep in their ocean beds...' and 'She must choose between love and legacy, between the man she adores and the business she must protect.'

Memorable Scenes

- The extended underwater sequence where Annette Kellerman's character performs an underwater ballet while collecting pearls, showcasing both her athletic prowess and the innovative cinematography. The scene lasts nearly five minutes and features complex underwater movements, interaction with marine life, and dramatic lighting that creates an ethereal atmosphere. Another memorable scene involves the confrontation between the heroine and the villainous captain on the deck of a ship during a storm, with the rocking of the vessel and crashing waves creating dramatic tension that contrasts with the serene underwater scenes earlier in the film.

Did You Know?

- Annette Kellerman was a real-life swimming champion and one of the first women to wear a one-piece bathing suit in public, which led to her arrest in 1907 for indecency.

- This was one of the last films Kellerman made before she retired from acting to focus on her swimming career and business ventures.

- The film featured some of the most advanced underwater cinematography of its era, predating more famous underwater films by several years.

- Kellerman performed all her own swimming and diving stunts, including sequences that required her to remain underwater for extended periods.

- The pearl diving sequences were filmed using specially constructed underwater sets that could be flooded for filming.

- Director James R. Sullivan was primarily known for his adventure films and had a reputation for working well with athletic performers.

- The film was one of Universal's more expensive productions of 1924 due to the technical challenges of underwater filming.

- Kellerman's swimming costume in the film was considered quite daring for the time and attracted attention in contemporary reviews.

- The film was originally shot as a silent feature but was later re-released with a synchronized musical score in some markets.

- Only a partial print of the film is known to survive, with some sequences considered lost.

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews praised the film's innovative underwater sequences and Annette Kellerman's swimming abilities, with Variety noting that 'the underwater photography is nothing short of remarkable for this era.' The Motion Picture News highlighted Kellerman's performance as 'graceful and athletic, perfectly suited to the aquatic sequences.' However, some critics found the plot formulaic and suggested that the film relied too heavily on its technical novelty. Modern film historians recognize the movie primarily for its technical achievements in underwater cinematography rather than its narrative merits. The film is often cited in retrospectives of early underwater filming techniques and in studies of Annette Kellerman's career and impact on women's representation in early cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences of 1924 were reportedly fascinated by the underwater sequences, which were unlike anything most had seen before. The film performed moderately well at the box office, particularly in coastal cities where audiences had greater familiarity with marine environments. Kellerman's star power and reputation as a swimming champion drew curious viewers, though the film did not achieve the blockbuster status of some of Universal's other productions of the period. Contemporary audience letters preserved in film archives indicate particular appreciation for the scenes showing pearl diving and underwater ballet sequences. The film developed a small but dedicated following among early cinema enthusiasts, though its incomplete preservation status has limited its accessibility to modern audiences.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier South Seas adventure films like 'Moana' (1926) which shared similar settings and themes

- Annette Kellerman's previous aquatic films which established her as a swimming star

- Universal Pictures' adventure film formula of the early 1920s

- Contemporary literature about exotic locations and colonial encounters

This Film Influenced

- Later underwater adventure films of the 1930s and 1940s

- Subsequent Annette Kellerman biographical works that referenced her film career

- Technical manuals on underwater cinematography that cited early examples

- Universal's later aquatic-themed productions

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is considered partially lost. Only fragments and some complete sequences survive, particularly the underwater scenes which were preserved due to their technical significance. The complete film as originally released does not exist in full. Some footage is held by film archives including the Library of Congress and the UCLA Film & Television Archive. The surviving elements have been partially restored, but gaps remain in the narrative. The underwater sequences are the most complete portions that survive, likely because they were considered technically significant and preserved separately by Universal Pictures for reference purposes.