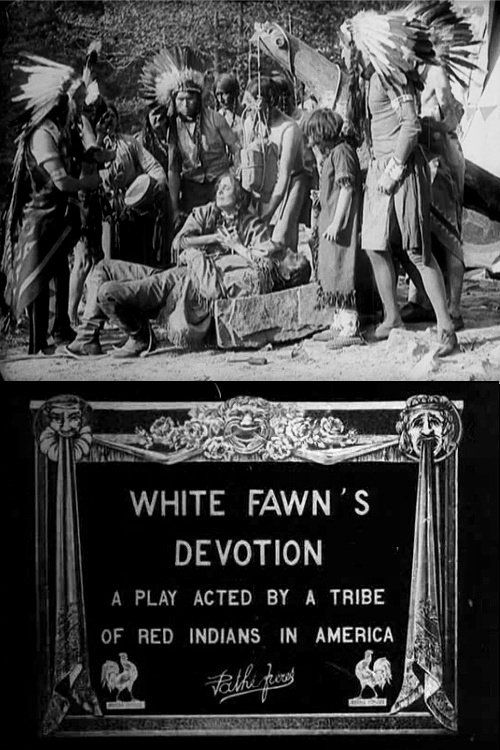

White Fawn's Devotion: A Play Acted by a Tribe of Red Indians in America

"A Dramatic Story of Indian Life and Justice"

Plot

In this early silent Western drama, a young Native American child frantically rushes to her tribal chief with devastating news that her father has killed her mother. The tribe immediately mobilizes, pursuing the accused father through the wilderness and eventually capturing him. As they drag him back to face tribal justice, the true circumstances of the incident are revealed through a dramatic flashback - the death was actually an accident during a hunting trip. The film concludes with the tribe's understanding and forgiveness, showcasing themes of justice, misunderstanding, and reconciliation within Native American communities.

Director

James Young DeerCast

About the Production

This was one of the earliest films directed by a Native American filmmaker and featured an almost entirely Native American cast. The film was shot in a single day, typical of one-reel productions of the era. James Young Deer insisted on authentic Native American casting and consulted with tribal elders to ensure cultural accuracy in the depiction of tribal justice systems.

Historical Background

This film was produced during the early silent era when the film industry was still establishing its conventions and practices. 1910 was a pivotal year in cinema, as feature-length films were beginning to emerge and studios were becoming more organized. The film also emerged during a period when Native Americans were largely being displaced from their lands and their cultures were being systematically suppressed. James Young Deer's work represented a rare instance of Native American self-representation during an era of rampant misrepresentation and stereotypes in popular media.

Why This Film Matters

White Fawn's Devotion holds immense cultural significance as one of the earliest examples of Native American filmmakers telling their own stories. It challenged the prevailing stereotypes of Native Americans as savage or primitive that dominated early cinema. The film's authentic portrayal of tribal justice and family dynamics provided a counter-narrative to the typical Western genre portrayals. It paved the way for future Native American filmmakers and demonstrated the importance of authentic cultural representation in media. The collaboration between Young Deer and St. Cyr represents an early example of creative partnerships between marginalized artists in Hollywood.

Making Of

James Young Deer, of Nanticoke heritage, broke significant barriers by becoming one of the first Native American directors in the emerging film industry. He insisted on authentic casting, which was revolutionary for an era when white actors typically portrayed Native Americans in redface. Young Deer worked closely with his wife Lilian St. Cyr to ensure accurate cultural representation. The production faced challenges from studio executives who wanted more sensationalized portrayals of Native Americans, but Young Deer fought to maintain authenticity. The film was shot quickly in a single day using natural lighting, and the cast wore authentic tribal regalia rather than Hollywood costumes.

Visual Style

The film utilized the naturalistic cinematography style that James Young Deer pioneered, with extensive use of location shooting rather than studio sets. The camera work was straightforward but effective, using medium shots to capture the actors' performances and wider shots to establish the wilderness setting. The film employed the cross-cutting technique that was becoming common in 1910 to build tension during the chase sequence.

Innovations

While not technically innovative in terms of camera work, the film was groundbreaking in its approach to casting and cultural authenticity. Young Deer's insistence on using actual Native American actors and authentic costumes and customs was revolutionary for the period. The film's efficient one-day shooting schedule demonstrated the growing professionalism of the film industry.

Music

As a silent film, it would have been accompanied by live musical performance during exhibition. Typical accompaniment would have included piano or organ music, with selections ranging from classical pieces to popular songs of the era. The music would have been chosen to enhance the dramatic moments, particularly during the chase and revelation sequences.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, dialogue was conveyed through intertitles and pantomime rather than spoken dialogue

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic chase sequence where the tribe pursues the accused father through the wilderness, showcasing both the tension of the pursuit and the natural beauty of the landscape

Did You Know?

- James Young Deer was the first documented Native American film director in Hollywood history

- Lilian St. Cyr (Winnebago/Ho-Chunk), who played White Fawn, was one of the first Native American film actresses and worked under the stage name Princess Red Wing

- The film is believed to be the earliest surviving film directed by a Native American

- This was part of a series of films Young Deer made for Pathé focusing on authentic Native American stories

- The full title 'White Fawn's Devotion: A Play Acted by a Tribe of Red Indians in America' reflects the early film practice of descriptive titles

- The film was shot in the naturalistic style that Young Deer pioneered, avoiding the stereotypical 'Indian' portrayals common in the era

- The tribal justice depicted was based on actual Native American conflict resolution practices

- Young Deer was married to Lilian St. Cyr, making this a collaboration between pioneering Native American filmmakers

- The film was distributed internationally and was particularly popular in European markets

- Only fragments of the film are believed to survive today, making it a partially lost film

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews in trade publications like The Moving Picture World praised the film for its authenticity and dramatic power. Critics noted the novelty of seeing actual Native Americans portraying themselves on screen. Modern film historians consider the film a landmark in Native American cinema and an important early example of minority self-representation in film. The film is frequently cited in academic studies of early cinema and Native American media representation.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1910 reportedly responded positively to the film's emotional story and authentic portrayal of Native American life. The film was particularly successful in urban areas where audiences were hungry for diverse content. Modern audiences who have seen surviving fragments often express surprise at the sophisticated storytelling and respectful representation, especially considering the era in which it was made.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Contemporary D.W. Griffith films

- Earlier Pathé productions

- Traditional Native American storytelling traditions

This Film Influenced

- Later Native American-directed films

- John Ford's more sympathetic Western portrayals

- Modern Indigenous cinema movement

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Partially lost - only fragments of the film are known to survive in various film archives. Some portions exist in the Library of Congress collection and at the British Film Institute. The incomplete status makes it a rare and historically significant artifact of early Native American cinema.