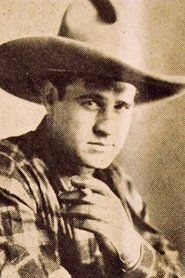

Wolf Lowry

"The Story of a Man Who Fought the Devil in His Own Heart"

Plot

Wolf Lowry is a classic silent Western that follows the story of a rough-hewn rancher named Wolf Lowry, portrayed by William S. Hart, who lives a solitary life in the American West. When young homesteader Mary Brown (Margery Wilson) and her father arrive in the area, Wolf initially clashes with them but gradually develops feelings for Mary. The plot intensifies when local cattle rustlers threaten the new settlers, forcing Wolf to choose between his isolated lifestyle and defending the community he's come to care about. Through a series of dramatic confrontations and personal transformations, Wolf ultimately embraces his role as a protector of the innocent, culminating in a showdown that tests his honor and resolve. The film concludes with Wolf having found redemption through his actions, though true to Hart's character archetype, he eventually rides off alone into the sunset.

About the Production

Wolf Lowry was filmed during the golden age of silent Westerns when William S. Hart was at the peak of his popularity. The production utilized authentic Western locations and props, with Hart insisting on realism in every aspect of the filming. The movie was shot during the summer of 1917 when California's drought conditions provided the perfect dusty, arid landscape typical of Western settings. Hart, known for his method approach to acting, performed many of his own stunts, including dangerous horseback riding sequences that would later become his trademark.

Historical Background

Wolf Lowry was produced and released during a pivotal period in American history, as the United States was deeply involved in World War I. The film's themes of individual heroism and moral clarity resonated strongly with wartime audiences seeking straightforward narratives of good versus evil. 1917 was also a significant year for the film industry, as Hollywood was consolidating its position as the world's entertainment capital while the war disrupted European film production. William S. Hart, already a major star, was at the height of his popularity during this period, and his films served as cultural touchstones for Americans grappling with the changes brought by modernization and war. The Western genre itself was evolving from simple action stories to more complex morality plays, with Hart leading this transformation through films like Wolf Lowry that explored the psychological dimensions of frontier life. The movie's release coincided with the Russian Revolution and major shifts in global politics, making its focus on American frontier values particularly appealing to domestic audiences seeking stability and familiar narratives.

Why This Film Matters

Wolf Lowry represents a crucial milestone in the development of the Western genre and American cinema more broadly. The film helped cement William S. Hart's signature 'good bad man' archetype, a complex protagonist who lives outside society's laws but maintains a personal moral code that ultimately serves justice. This character type would influence countless Western films and actors who followed, from John Wayne to Clint Eastwood. The movie also exemplifies the transition from early cinema's simplistic melodramas to more psychologically sophisticated storytelling, with Hart bringing unprecedented emotional depth to the Western hero. Wolf Lowry's success demonstrated the commercial viability of serious Western dramas, paving the way for the genre's golden age in the 1930s-1950s. The film's portrayal of the American West as a place of moral testing and personal transformation contributed to the mythologizing of the frontier that remains central to American cultural identity. Additionally, the movie's preservation status makes it an invaluable historical document of early Hollywood filmmaking techniques and visual storytelling methods.

Making Of

The making of Wolf Lowry exemplified William S. Hart's meticulous approach to Western filmmaking. Hart, who had real experience as a cowboy and ranch hand, insisted on absolute authenticity in every detail, from the costumes to the dialogue cards. He worked closely with director Lambert Hillyer, with whom he had collaborated on several previous films, to ensure the story maintained the moral complexity that characterized his best work. The cast was chosen with Hart's direct involvement, and he personally coached Margery Wilson in her performance, helping her transition from her previous comedy roles to the more serious dramatic requirements of a Western heroine. The film was shot during an unusually hot California summer, with cast and crew often working in temperatures exceeding 100 degrees. Hart's dedication to realism extended to performing his own riding stunts, a practice that occasionally worried producers but always delivered spectacular results on screen. The production was completed in just three weeks, remarkably fast even by silent film standards, thanks to Hart's efficient management and his team's familiarity with his working methods.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Wolf Lowry, handled by Joseph H. August, exemplified the visual sophistication that characterized Hart's productions. August employed natural lighting techniques that took advantage of California's harsh sunlight to create the stark, high-contrast images that became synonymous with the Western genre. The film's outdoor sequences showcase a mastery of landscape photography, with wide shots emphasizing the isolation and majesty of the Western setting while close-ups captured the subtle emotional nuances of Hart's performance. The camera work was notably fluid for its time, with tracking shots during horseback riding sequences that created a sense of movement and energy unusual in 1917 productions. August's use of shadow and light in interior scenes added psychological depth to key dramatic moments, particularly in the film's moral crisis sequences. The visual storytelling relied on carefully composed images that conveyed character relationships and emotional states without the need for excessive intertitles, demonstrating the sophisticated visual literacy that had developed in cinema by this period.

Innovations

Wolf Lowry demonstrated several technical innovations that were advanced for 1917 filmmaking. The production utilized portable cameras that allowed for greater mobility in outdoor sequences, enabling more dynamic filming of horseback riding and chase scenes than was typical in earlier Westerns. The film's editing employed sophisticated cross-cutting techniques to build tension during action sequences, particularly in the climactic showdown scene where parallel actions were intercut to create suspense. The makeup techniques used to age Hart's character for certain scenes were notably subtle and effective for the period, avoiding the heavy-handed applications common in many contemporary films. The production also made effective use of location shooting rather than relying on studio backdrops, requiring advances in equipment transportation and power supply that facilitated filming in remote areas. The film's preservation in archives has allowed modern scholars to study the technical craftsmanship of the period, including the sophisticated matte painting techniques used to extend outdoor sets and create the illusion of vast Western landscapes.

Music

As a silent film, Wolf Lowry would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical presentation would have featured a piano or organ player providing musical accompaniment, with larger theaters employing small orchestras. The musical score would have been compiled from various published pieces appropriate to the mood of each scene, with dramatic moments accompanied by stirring classical excerpts and romantic sequences featuring popular ballads of the era. While no original score documentation survives for Wolf Lowry, contemporary accounts suggest that Hart's films were typically accompanied by carefully curated music that enhanced the emotional impact of key scenes. The musical accompaniment would have included familiar Western-themed compositions that audiences associated with frontier life, as well as original improvisations by skilled theater musicians. Modern screenings of the film often feature newly composed scores by silent film specialists who attempt to recreate the musical experience of 1917 while incorporating contemporary musical sensibilities.

Famous Quotes

'A man's gotta stand for something, or he'll fall for anything.' - Wolf Lowry

'The West ain't big enough for both of us... but it's big enough for one man with courage.' - Wolf Lowry

'Sometimes doing right means standing alone.' - Wolf Lowry

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic showdown where Wolf faces the cattle rustlers alone, demonstrating his transformation from isolated rancher to community protector. The scene is particularly memorable for Hart's subtle performance, conveying both fear and resolve through minimal gestures and intense facial expressions. The wide shots emphasize his isolation against the vast landscape, while close-ups capture the internal struggle that precedes his heroic action.

Did You Know?

- William S. Hart was not only the star but also had significant creative control over the production, as was typical for his films during this period.

- Margery Wilson, who played the female lead, would later become one of the few women directors of the silent era, though all of her directed films are now considered lost.

- The film was one of Hart's most successful releases of 1917, playing to packed theaters across America during World War I.

- Wolf Lowry's horse, a beautiful white steed named Fritz, became so popular that Hart received numerous letters from fans asking about the animal's welfare.

- The movie was filmed on the same ranch property that Hart later purchased and turned into his personal estate, which is now a historic landmark and museum.

- Contemporary reviews praised Hart's performance as 'more nuanced than his usual tough-guy roles,' showing greater emotional depth.

- The film's title character was partially inspired by real-life Western figures Hart had known during his youth in the Dakotas.

- Despite being over 100 years old, the film still exists in archives, making it one of Hart's better-preserved works.

- The movie's success helped establish the 'good bad man' archetype that would dominate Western films for decades.

- Hart's contract for this film included a clause giving him final approval on all aspects of production, from casting to final cut.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Wolf Lowry as one of William S. Hart's most accomplished works, with particular acclaim for his nuanced performance that balanced toughness with vulnerability. The Moving Picture World noted that 'Hart has never been better, bringing a depth of feeling to the character that elevates the entire production beyond the typical Western fare.' Variety highlighted the film's 'authentic atmosphere and genuine emotion,' calling it 'a must-see for all lovers of real Western drama.' Modern film historians and silent cinema scholars continue to regard Wolf Lowry as a significant work in Hart's filmography, often citing it as an example of his mature style and the sophisticated storytelling techniques that distinguished his films from other Westerns of the era. Critics have noted how the film's moral complexity and psychological realism set it apart from many contemporaneous Westerns that relied on simpler good-versus-evil narratives. The movie is frequently referenced in academic studies of early American cinema as an important example of how the Western genre evolved from simple action entertainment to serious artistic expression.

What Audiences Thought

Wolf Lowry was enthusiastically received by audiences in 1917, becoming one of the year's box office successes for William S. Hart. Contemporary newspaper reports described packed theaters and enthusiastic audience responses, with many viewers reportedly moved to tears by the film's emotional climax. The movie resonated particularly strongly with rural audiences and those with connections to Western life, who appreciated Hart's authentic portrayal of frontier values and his respect for the land and its people. Hart's fan mail from this period indicates that audiences identified strongly with the Wolf Lowry character's struggle between isolation and community, a theme that struck a chord during the wartime period when many Americans were experiencing similar tensions between individual desires and collective responsibilities. The film's success helped solidify Hart's status as one of the most popular and respected actors of the silent era, with his name alone becoming sufficient to guarantee box office success. Audience appreciation for the film endured through subsequent decades, with revival screenings in the 1920s and 1930s still drawing appreciative crowds, testament to the lasting appeal of Hart's particular brand of Western storytelling.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Hart's own experiences as a real cowboy

- Contemporary dime novel Westerns

- The works of Owen Wister (particularly 'The Virginian')

- Classical Western mythology

- Biblical stories of redemption

This Film Influenced

- Later William S. Hart Westerns

- John Ford's early Westerns

- The 'good bad man' archetype in subsequent Westerns

- Psychological Westerns of the 1950s

- Revisionist Westerns of the 1960s-70s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Wolf Lowry is considered to be a partially preserved film. While the complete film exists in archives, some sequences have suffered from nitrate decomposition over the decades. The Library of Congress maintains a copy, and portions have been restored by film preservationists. The film is not considered completely lost, unlike many of Hart's other works, making it an important surviving example of his artistic output during his peak years. Several archives, including the Museum of Modern Art and the UCLA Film & Television Archive, hold prints or fragments of the film, ensuring its continued availability for study and exhibition. Restoration efforts have focused on stabilizing the existing footage and reconstructing missing elements from various sources when possible.