Zohra

Plot

Zohra tells the story of a young European girl who survives a devastating shipwreck off the North African coast. She is discovered and rescued by members of a local tribe, whose chief takes pity on the orphaned child and decides to raise her as his own. The chief names her Zohra and she grows up immersed in the tribal culture, learning their customs, language, and way of life. As she matures into a young woman, Zohra becomes torn between her adopted family and the European world she was born into, especially when European traders and officials arrive in the region. The film culminates in a dramatic conflict that forces Zohra to choose between her two identities, ultimately revealing the complex intersections of colonialism, cultural identity, and personal loyalty in early 20th century North Africa.

Director

Albert Samama ChiklyCast

About the Production

Filmed using a hand-cranked camera with natural lighting, the production faced significant challenges including the lack of established film infrastructure in Tunisia. Director Albert Samama Chikly, a pioneering filmmaker and photographer, used his personal collection of equipment and modified many devices to suit the North African environment. The film was shot on location with authentic tribal settings and costumes, revolutionary for its time in depicting indigenous North African life authentically rather than through European exoticism.

Historical Background

Zohra was created during the French Protectorate period in Tunisia (1881-1956), when North African territories were under colonial rule. The early 1920s saw the emergence of national consciousness across the Arab world, with growing resistance to colonial domination. Cinema was primarily a European import, used by colonial powers to reinforce cultural dominance and exoticize indigenous peoples. Against this backdrop, Albert Samama Chikly's decision to create a film that portrayed North African culture from an insider's perspective was revolutionary. The film emerged alongside the early Egyptian film industry, which would soon become the dominant force in Arab cinema. The post-World War I period also saw technological advances in filmmaking, making cameras more portable and film stock more sensitive, enabling location shooting that had been difficult in previous decades. This context makes Zohra not just an artistic achievement but a political statement about cultural autonomy and representation.

Why This Film Matters

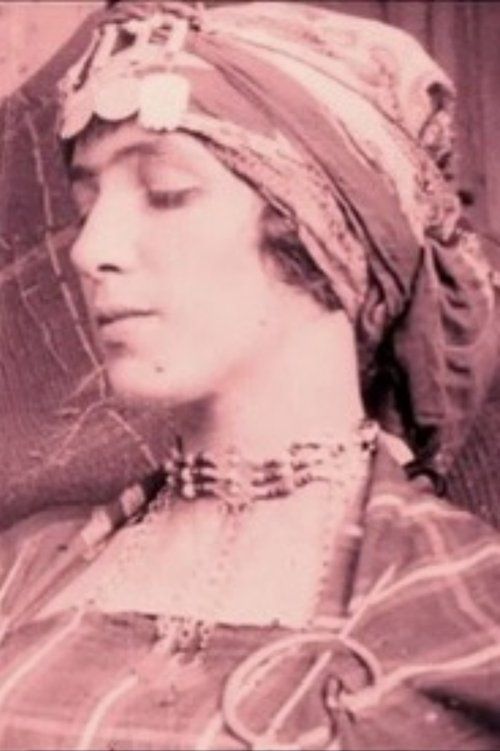

Zohra represents a watershed moment in Arab and African cinema history, challenging the dominant narrative that cinema in these regions began with European colonial productions. The film's existence demonstrates that indigenous filmmakers were active in the very early days of cinema, creating works that reflected their own cultural perspectives rather than colonial fantasies. Its portrayal of North African society with dignity and authenticity stood in stark contrast to the exoticized and often demeaning representations common in European films of the era. The film also broke ground by featuring a local woman, Hayde Chikly, as the protagonist, challenging both colonial and traditional gender norms. Zohra's rediscovery and restoration in the late 20th century sparked renewed interest in the history of early African cinema and led to scholarly reevaluation of the timeline of global film development. Today, it is celebrated as a foundational text of Tunisian national cinema and a testament to early resistance against cultural colonialism.

Making Of

The making of Zohra was a remarkable achievement in early cinema history. Albert Samama Chikly, a wealthy Tunisian businessman of Turkish-Italian descent, was passionate about the new medium of film and invested heavily in equipment from Europe. He converted part of his family estate into a makeshift studio and workshop. The production faced numerous technical challenges, including the extreme heat which affected the film stock, and the need to transport heavy equipment across difficult terrain to reach authentic filming locations. Hayde Chikly, despite having no acting experience, was coached intensively by her father and delivered a performance that was groundbreaking for its naturalism. The tribal scenes were filmed with the cooperation of local communities, who were initially suspicious of the filming process but eventually became enthusiastic participants. Chikly's innovative use of natural light and authentic locations set new standards for regional cinema, though the film's limited distribution meant these techniques had little immediate influence beyond Tunisia.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Zohra, while limited by the technology of 1922, showed remarkable innovation and artistry. Albert Samama Chikly employed natural lighting techniques that captured the harsh beauty of the North African landscape, using the intense Mediterranean sun to create dramatic contrasts that European filmmakers struggled to achieve. The film features sweeping shots of the Tunisian coastline and desert landscapes, demonstrating Chikly's understanding of the power of location shooting. Close-ups of Hayde Chikly reveal a sophisticated understanding of emotional expression through facial expression, while wide shots of tribal gatherings convey the communal aspects of North African society. The shipwreck sequence, filmed in actual waters, shows remarkable technical ambition for its time, with the camera capturing the chaos of the storm from multiple angles. Chikly's background as a photographer is evident in the film's careful composition and attention to visual detail, particularly in the depiction of traditional costumes, architecture, and rituals.

Innovations

Zohra achieved several technical milestones for its time and location. Albert Samama Chikly developed special camera housings to protect the equipment from sand and heat, innovations that were particularly advanced for the era. The film utilized location shooting extensively, which was rare in 1922, especially outside of major film production centers. Chikly also experimented with multiple camera angles and movement, including tracking shots that followed characters through the narrow streets of Tunis's medina. The shipwreck sequence featured some of the earliest examples of underwater filming in narrative cinema, achieved using specially designed waterproof camera housings. The film's editing techniques, particularly its use of cross-cutting between European and North African characters, demonstrated sophisticated narrative techniques that were still developing in mainstream cinema. These technical achievements were all the more remarkable given the lack of established film infrastructure in Tunisia at the time.

Music

As a silent film, Zohra originally featured live musical accompaniment during screenings, typically performed by local musicians using traditional Tunisian instruments including the oud, darbuka, and ney. The musical selections varied by venue, with urban theaters often employing European-style orchestral arrangements while rural screenings featured more traditional North African musical styles. In some screenings, particularly in Tunis, a hybrid approach was used, combining Western classical music with traditional Tunisian melodies to reflect the film's cultural themes. When the film was restored in the 1990s, a new score was commissioned that attempted to recreate the likely original musical experience, blending period-appropriate Western classical pieces with authentic Tunisian folk music. The restored version also features sound effects and limited dialogue intertitles, though these were not part of the original 1922 release.

Famous Quotes

"In naming her Zohra, we give her not just a name, but a destiny" - Tribal Chief

"The sea that took your old life has given you a new one" - Tribal Chief

"I am torn between two worlds, belonging fully to neither" - Zohra

"Your blood may be European, but your heart is now African" - Tribal Chief

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic shipwreck opening sequence, filmed in actual Mediterranean waters with real boats and storm conditions

- Zohra's ceremonial adoption into the tribe, featuring authentic tribal rituals and costumes

- The emotional confrontation scene where Zohra must choose between her European heritage and adopted North African family

- The sweeping landscape shots of the Tunisian coastline and desert, showcasing the beauty of the region

- The final scene where Zohra makes her definitive choice, captured in a close-up that became iconic in early Arab cinema

Did You Know?

- Zohra is widely considered the first feature-length narrative film made in Tunisia and one of the first in the entire Arab world.

- The film starred Hayde Chikly, the director's daughter, making her one of the first North African women to star in a feature film.

- Albert Samama Chikly was not only a filmmaker but also an inventor who built his own cameras and projection equipment.

- The film was shot without a script, with Chikly improvising scenes and dialogue as they went along.

- Zohra was one of the first films to use non-professional local actors rather than imported European performers.

- The original negative was thought lost for decades until a damaged copy was discovered in the French film archives in the 1960s.

- Chikly used his personal fortune to finance the film, as no established film industry existed in Tunisia at the time.

- The film premiered at the Omnia Pathé cinema in Tunis, one of the first movie theaters in North Africa.

- Despite its historical importance, the film was banned in several European colonies due to its sympathetic portrayal of indigenous North African culture.

- The shipwreck scene was filmed using real boats in the Mediterranean Sea, with the crew risking their equipment and safety to capture authentic footage.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception to Zohra was limited due to its restricted distribution, but the few reviews that appeared in European film journals were surprisingly positive, noting its authentic portrayal of North African life and technical competence. French colonial authorities viewed the film with suspicion, concerned about its potential to inspire nationalist sentiments. In the decades following its release, the film was largely forgotten until its rediscovery in the 1960s, when film historians began recognizing its historical importance. Modern critics have praised Zohra for its pioneering status and its resistance to colonial cinematic conventions, though they also note its technical limitations compared to contemporary European productions. The film is now studied in film schools worldwide as an example of early non-Western cinema and is frequently cited in discussions about decolonizing film history.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception in Tunisia was enthusiastic, with local viewers excited to see their culture and landscapes represented on screen for the first time. The film's premiere at the Omnia Pathé cinema in Tunis drew large crowds, including many who had never before seen a moving picture. European expatriate audiences were divided, with some praising the film's authenticity while others criticized it for deviating from the exoticized depictions they expected. In subsequent years, as political tensions increased under colonial rule, the film gained underground popularity as a symbol of cultural resistance. Modern audiences, particularly in Tunisia and across the Arab world, have embraced Zohra as a cultural treasure, with screenings at film festivals and retrospectives drawing enthusiastic responses. The film's themes of cultural identity and resistance continue to resonate with contemporary viewers dealing with post-colonial identity issues.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- European colonial travelogues

- Arab oral storytelling traditions

- French realist literature of the period

- Early Italian neorealist cinema

- Traditional Tunisian theater forms

This Film Influenced

- Early Egyptian feature films of the 1920s and 1930s

- Subsequent Tunisian cinema

- Post-colonial African cinema

- Films dealing with cultural hybridity and identity

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Zohra was considered a lost film for several decades until a damaged but viewable print was discovered in the French Cinémathèque archives in 1964. The discovered print was incomplete and in poor condition, with significant deterioration and missing scenes. In the 1990s, a major restoration effort was undertaken by the Tunisian National Film Archive in collaboration with the French Cinémathèque, using advanced digital techniques to stabilize and enhance the surviving footage. While approximately 15-20 minutes of the original film remains lost, the restored version represents the most complete version currently available. The restored film has been preserved in both digital and 35mm formats and is periodically screened at film festivals and special retrospectives. Additional fragments continue to be sought in private collections and lesser-known archives.