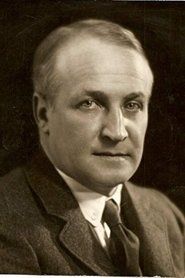

Robert Flaherty

Director

About Robert Flaherty

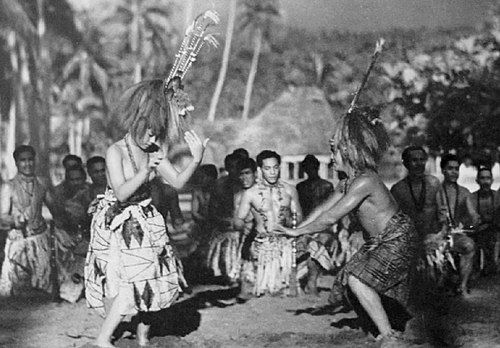

Robert Joseph Flaherty (February 16, 1884 – July 23, 1951) was an American filmmaker who revolutionized cinema by creating the first commercially successful documentary feature film, 'Nanook of the North' in 1922. Originally trained as a mining engineer and explorer, Flaherty began his career documenting his expeditions to the Hudson Bay region, where he developed his passion for filming indigenous peoples and their relationship with nature. After losing his initial film footage in a fire, he returned to the Arctic to create 'Nanook of the North,' which established many conventions of documentary filmmaking and made him an international sensation. His follow-up film 'Moana' (1926), shot in Samoa, prompted John Grierson to coin the term 'documentary' to describe Flaherty's work. Throughout his career, Flaherty struggled with funding and creative control, leading to a relatively small but influential body of work including 'Man of Aran' (1934), 'The Land' (1942), and his final masterpiece 'Louisiana Story' (1948). Despite controversies over his methods of staging scenes, Flaherty's poetic approach to documenting traditional ways of life and his technical innovations in location filming fundamentally shaped the documentary genre. His films emphasized the dignity of human labor and the harmony between people and their environment, creating a romantic vision of disappearing cultures that continues to influence filmmakers today.

The Craft

Behind the Camera

Flaherty's directing style combined observational documentary techniques with staged dramatic sequences, creating what he called 'living drama.' He spent months or even years living among his subjects to build trust and understand their way of life before filming. His approach emphasized long takes, natural lighting, and the relationship between humans and their environment. Flaherty often staged scenes to capture the essence of traditional life that was no longer practiced, believing this served a higher truth than strict documentation. His visual style was poetic and romantic, using the landscape as a character and focusing on the dignity of human labor. He pioneered techniques like shooting in extreme weather conditions, using portable cameras, and capturing authentic performances from non-professional subjects.

Milestones

- Directed 'Nanook of the North' (1922), the first feature-length documentary

- Pioneered documentary filmmaking techniques and conventions

- Filmed 'Moana' (1926) in Samoa, inspiring the term 'documentary'

- Created 'Man of Aran' (1934) documenting life on the Aran Islands

- Directed 'Louisiana Story' (1948), which won an Academy Award

- Established the observational style of documentary filmmaking

- Pioneered location filming techniques in remote, challenging environments

Best Known For

Must-See Films

Accolades

Won

- Academy Award for Best Writing (Motion Picture Story) for Louisiana Story (1948)

- Venice Film Festival Mussolini Cup for Best Foreign Film for Man of Aran (1934)

- National Board of Review Award for Best Documentary for The Land (1942)

Nominated

- Academy Award nomination for Best Documentary Feature for Louisiana Story (1948)

- Venice Film Festival Golden Lion nomination for Louisiana Story (1948)

- BAFTA nomination for Best Documentary Film for Louisiana Story (1949)

Special Recognition

- Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (1960)

- Inducted into the International Documentary Association Hall of Fame

- The Flaherty Film Seminar established in his honor (1955)

- Named one of the 100 Most Influential People in Documentary Film by Documentary Magazine

Working Relationships

Worked Often With

Studios

Why They Matter

Impact on Culture

Robert Flaherty fundamentally changed how the world understood both documentary filmmaking and indigenous cultures. His film 'Nanook of the North' created an international sensation and established the feature-length documentary as a viable commercial art form. Flaherty's work introduced Western audiences to the lives of people in remote regions, creating empathy and fascination with traditional ways of life. His films influenced public perceptions of the Arctic, Pacific islands, and rural America, often romanticizing these cultures but also bringing attention to their struggles. The technical innovations he developed for filming in extreme conditions paved the way for future documentary and narrative filmmakers working on location. Flaherty's emphasis on the relationship between humans and their environment anticipated later environmental movements and ecological consciousness in cinema.

Lasting Legacy

Flaherty's legacy is complex and enduring, as he is simultaneously celebrated as the father of documentary film and criticized for his ethically questionable methods. The annual Flaherty Film Seminar, established shortly after his death, remains one of the most prestigious forums for documentary filmmakers worldwide. His films are studied in film schools as foundational texts of documentary cinema, despite ongoing debates about their authenticity. Flaherty's influence can be seen in the work of countless documentarians who followed, from the Direct Cinema movement of the 1960s to contemporary nature documentaries. The techniques he pioneered—long observational takes, location shooting with natural light, and intimate portraits of daily life—have become standard practices in documentary filmmaking. His vision of cinema as a means of exploring human dignity and our relationship with nature continues to inspire filmmakers seeking to use the medium for artistic and social purposes.

Who They Inspired

Flaherty's influence extends across multiple generations of filmmakers and genres. Documentary filmmakers like Werner Herzog, Errol Morris, and David Attenborough have acknowledged his impact on their work. Narrative directors such as Terrence Malick and Kelly Reichardt have been influenced by his poetic approach to landscape and human labor. The British Documentary Movement, led by John Grierson, was directly inspired by Flaherty's work. His influence can also be seen in ethnographic film, nature documentaries, and even reality television, which often borrows his techniques of staging reality for dramatic effect. Contemporary filmmakers continue to grapple with the ethical questions Flaherty raised about the relationship between filmmaker and subject, authenticity and artifice, making his work perpetually relevant to discussions about documentary ethics.

Off Screen

Flaherty married Frances Hubbard in 1914, who became his lifelong collaborator and essential partner in his filmmaking endeavors. Frances was deeply involved in the research, writing, and editing aspects of his films, often working alongside him in remote locations. The couple had three children: Barbara, David, and Monica. Flaherty's career was marked by financial struggles and conflicts with producers, often putting his family through periods of hardship. Despite these challenges, Frances remained his staunchest supporter and creative partner throughout his career. Flaherty was known for his restless spirit and love of adventure, traits that both fueled his filmmaking and strained his family life. He died of a heart attack in Vermont in 1951, leaving behind a complex legacy as both a pioneer and a controversial figure in documentary cinema.

Education

Attended Michigan College of Mines (now Michigan Technological University) for mining engineering, though he did not graduate. Also studied at the Upper Canada College in Toronto. His real education came from his work as an explorer and prospector in northern Canada, where he learned photography and developed his interest in documenting indigenous peoples.

Family

- Frances Hubbard (1914-1951)

Did You Know?

- Flaherty originally worked as a prospector and explorer for Canadian railway companies before becoming a filmmaker

- His first film footage, shot in 1914-1915, was destroyed when he dropped a cigarette on the highly flammable nitrate film

- For 'Nanook of the North,' Flaherty paid his Inuit subjects with food, tools, and other supplies rather than money

- The famous igloo scene in 'Nanook' was shot in a three-sided igloo to allow enough light for filming

- Flaherty's 'Tabu' (1931) was co-directed with F.W. Murnau, but they had creative conflicts and Flaherty left before production was complete

- During filming of 'Man of Aran,' the islanders had to be taught how to hunt basking sharks, a practice they had abandoned decades earlier

- 'Louisiana Story' was funded by Standard Oil as a promotional film, though Flaherty managed to maintain his artistic vision

- Flaherty was the first person to shoot a feature film entirely on location in the Arctic

- He often lived with his subjects for months before filming to build trust and understand their culture

- The success of 'Nanook' made its subject, Allakariallak, an international celebrity, though he died of starvation two years after the film's release

In Their Own Words

Sometimes you have to lie. One often has to distort a thing to catch its true spirit.

I have been trying to tell a story of life, to catch the drama of the living man, to show his struggle against the forces of nature.

The camera is a liar. It shows what is on the outside of people, not what is on the inside.

I don't make documentaries, I make living drama.

All art is a kind of lying to tell the truth.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Robert Flaherty?

Robert Flaherty was an American filmmaker widely considered the father of documentary film. He pioneered the documentary genre with his groundbreaking feature 'Nanook of the North' (1922) and developed many techniques still used in documentary filmmaking today.

What films is Robert Flaherty best known for?

Flaherty is best known for 'Nanook of the North' (1922), 'Moana' (1926), 'Man of Aran' (1934), 'The Land' (1942), and 'Louisiana Story' (1948). These films established his reputation as a master of documentary filmmaking and poetic cinema.

When was Robert Flaherty born and when did he die?

Robert Joseph Flaherty was born on February 16, 1884, in New York City, and died of a heart attack on July 23, 1951, in Vermont at the age of 67.

What awards did Robert Flaherty win?

Flaherty won an Academy Award for Best Writing for 'Louisiana Story' (1948), the Venice Film Festival Mussolini Cup for 'Man of Aran' (1934), and received numerous other honors including a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

What was Robert Flaherty's directing style?

Flaherty's directing style combined observational documentary techniques with staged dramatic sequences. He emphasized long takes, natural lighting, and the relationship between humans and their environment, often living among his subjects for months before filming to build trust and understanding.

Why is Robert Flaherty controversial?

Flaherty is controversial because he often staged scenes and manipulated reality for dramatic effect, raising questions about documentary ethics. Critics argue his films present romanticized and sometimes inaccurate portrayals of traditional life, though defenders argue he captured essential truths about human dignity.

How did Robert Flaherty influence documentary filmmaking?

Flaherty established many conventions of documentary filmmaking including feature-length documentaries, location shooting in remote areas, observational techniques, and the use of non-professional subjects. His work inspired generations of documentarians and led to the creation of the annual Flaherty Film Seminar.

What was Robert Flaherty's background before filmmaking?

Before becoming a filmmaker, Flaherty worked as a mining engineer, prospector, and explorer in northern Canada. His experiences exploring remote regions and photographing indigenous peoples led him to documentary filmmaking.

Learn More

Films

2 films