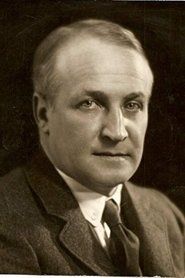

Moana

"A Romance of the South Seas"

Plot

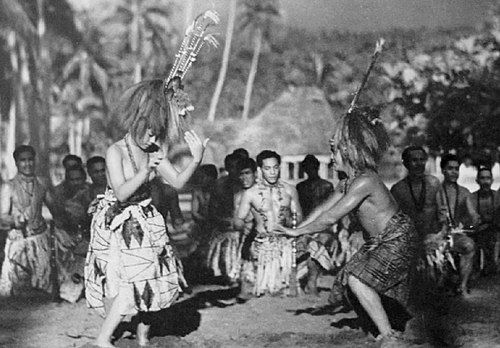

Robert Flaherty's groundbreaking documentary follows the life of a young Samoan man named Moana (played by Ta'avale) as he transitions from boyhood to adulthood in the traditional Samoan village of Safune. The film captures the daily rhythms of island life, including fishing, cooking, and communal activities, while focusing particularly on the traditional tattooing ceremony that marks Moana's passage into manhood. Through stunning visual poetry, Flaherty documents the harmonious relationship between the Samoan people and their natural environment, showing how they live in balance with the land and sea. The narrative culminates in Moana's successful completion of his adult trials, demonstrating his readiness to take his place as a full member of the community. Throughout, Flaherty presents an idealized vision of Samoan life, emphasizing what he described as the 'pride of beauty, pride of strength' that characterized this traditional culture.

About the Production

Flaherty and his family lived in Samoa for over a year during filming, building a house and integrating with the local community. The production faced numerous challenges including tropical diseases, difficult filming conditions, and the need to transport heavy equipment to remote locations. Flaherty famously staged certain scenes for dramatic effect, particularly the tattooing sequence, which he had to persuade the local people to perform specifically for the camera. The film was shot on nitrate stock, which has made preservation challenging over the decades.

Historical Background

The mid-1920s represented both the height of the silent film era and the beginning of serious ethnographic filmmaking. When 'Moana' was produced, the concept of documentary filmmaking was still in its infancy, with Flaherty's earlier 'Nanook of the North' (1922) being the only major precedent. The 1920s saw growing Western fascination with 'exotic' cultures, fueled by increased travel and anthropological interest. This period also coincided with the height of colonialism, when Western powers controlled many Pacific islands. Samoa was under New Zealand administration at the time, and Western influence was already beginning to change traditional Samoan life. The film emerged during the Jazz Age, when American audiences were hungry for escapist entertainment and visions of paradise. It was also a time of significant technical innovation in cinema, with improvements in portable cameras making location filming more feasible. The film's release came just before the transition to sound in cinema, making it one of the last major silent documentaries of its era.

Why This Film Matters

'Moana' holds a pivotal place in cinema history as the film that literally gave the documentary genre its name. John Grierson's review, in which he first used the term 'documentary' to describe Flaherty's work, established the vocabulary for non-fiction filmmaking that continues to this day. The film pioneered the observational documentary style, though Flaherty's methods of staging scenes for dramatic effect would spark debates about documentary ethics that continue in the field. 'Moana' also established the template for the ethnographic film, influencing generations of anthropologists and documentary filmmakers. Its romanticized vision of 'primitive' paradise, while now criticized as colonial fantasy, reflected and shaped Western attitudes toward Pacific Island cultures. The film's visual poetry and emphasis on the beauty of traditional life helped establish documentary as an art form rather than merely educational or journalistic work. Its influence can be seen in later nature documentaries, travelogues, and ethnographic films. The film also represents an important early attempt to capture indigenous cultures on film, creating a visual record of Samoan traditions that were already changing due to Western influence.

Making Of

Robert Flaherty's approach to making 'Moana' was revolutionary for its time, involving an unprecedented commitment to living among his subjects. He arrived in Samoa in 1923 with his family and spent over a year immersing himself in the local culture before even beginning principal photography. Flaherty built a Western-style house in the village but made efforts to participate in daily life, learning the language and customs. His method involved observing the community for months, then reconstructing traditional activities for the camera - a practice that would later be criticized as manipulative but which he defended as necessary to capture the essence of a culture before it disappeared. The famous tattooing sequence required extensive negotiation with village elders, as the practice was becoming rare. Flaherty's wife Frances not only edited the film but also managed the complex logistics of the production and served as a cultural liaison. The production was plagued by tropical storms that damaged equipment, and Flaherty suffered from malaria during filming. Despite these challenges, he accumulated over 100,000 feet of footage, which he then spent a year editing down to create the final film.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Moana,' primarily handled by Flaherty himself with assistance from Ernest B. Schoedsack, was groundbreaking for its time. Shot entirely on location in Samoa using portable cameras, the film captured the lush tropical landscape with unprecedented intimacy and beauty. Flaherty employed natural lighting to dramatic effect, particularly in underwater sequences that were technically remarkable for the 1920s. The camera work emphasizes the relationship between the Samoan people and their environment, with many shots framed to show humans as part of the natural world rather than separate from it. Long takes and observational shots create a sense of immediacy and authenticity, even in staged scenes. The film makes extensive use of the tropical setting, with palm trees, beaches, and ocean waves serving as both backdrop and active elements in the visual narrative. Close-ups are used sparingly but effectively, particularly in the tattooing sequence where they emphasize the pain and endurance of the young man. The cinematography achieves a painterly quality that reflects Flaherty's background as a visual artist, creating images that are both documentary and artistic.

Innovations

Moana' represented several significant technical achievements in early documentary filmmaking. The underwater photography was particularly groundbreaking, with Flaherty and his team developing special waterproof camera housings to capture scenes beneath the Pacific waves. The filming of the tattooing sequence required innovative lighting solutions to capture the detailed work in traditional Samoan dwellings. The production team also developed portable power generation systems to operate cameras and lighting equipment in remote locations without electricity. The film's location shooting in tropical conditions pushed the limits of 1920s camera technology, with the crew having to protect sensitive equipment from humidity, salt water, and extreme heat. The extensive use of natural lighting was innovative for documentary work, requiring careful planning and timing to capture scenes in optimal conditions. The film also pioneered techniques for filming traditional activities, developing methods for unobtrusive camera placement that would influence documentary filmmaking for decades. Perhaps most significantly, 'Moana' demonstrated that feature-length documentary filmmaking was technically feasible in remote locations, paving the way for future ethnographic and nature documentaries.

Music

As a silent film, 'Moana' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The type of accompaniment varied by venue, ranging from full orchestras in major theaters to solo piano in smaller cinemas. While no original score was composed specifically for the film, theaters typically used compiled scores featuring tropical or exotic-themed music popular in the 1920s. Some performances included Samoan music or instruments when available, though authentic Samoan musicians were rarely featured in American theaters. The film's visual rhythm and pacing suggest it would have been suited to flowing, melodic accompaniment rather than the dramatic, action-oriented scores common to narrative films of the era. Modern restorations have been accompanied by newly composed scores that attempt to blend Western and Samoan musical elements. These contemporary scores often incorporate traditional Samoan instruments and melodies alongside Western orchestral arrangements, reflecting a more culturally sensitive approach than was common in the 1920s.

Famous Quotes

A documentary film - a new form of cinema that captures the drama of everyday life.

John Grierson's review that coined the term 'documentary',

I have tried to make a picture that would show the beauty of these people in their own setting.

Robert Flaherty,

The pride of beauty, the pride of strength.

Flaherty's description of what he sought to capture

In Samoa, life is lived as it should be lived.

Intertitle from the film

The sea gives, and the sea takes away.

Intertitle reflecting Samoan philosophy

Memorable Scenes

- The extended tattooing ceremony showing Moana's painful rite of passage into manhood, with close-ups capturing both his endurance and the intricate traditional tattoo work

- The underwater sequence of Moana diving for pearls, showcasing groundbreaking underwater cinematography and the beauty of Pacific marine life

- The communal feast scene demonstrating traditional Samoan food preparation and the importance of shared meals in village life

- The opening shots of the Samoan landscape, establishing the film's visual poetry and connection between people and environment

- The sequence of traditional fishing methods, showing the sophisticated techniques Samoans developed for catching fish

- The final scenes of Moana as an adult, demonstrating his successful transition to manhood and acceptance in the community

Did You Know?

- The term 'documentary' was first coined by Scottish filmmaker John Grierson specifically to describe 'Moana', calling it 'a documentary film' in his review.

- Flaherty's wife Frances served as the film's editor and was crucial to the production, managing the family and local relations during their year-long stay in Samoa.

- The young man playing Moana, Ta'avale, was not actually named Moana - Flaherty gave him this name for the film as it means 'ocean' in Samoan.

- Many scenes were staged, including the famous sequence of Moana diving for pearls, which was not a traditional Samoan activity but was added for dramatic appeal.

- The film was a commercial failure upon its initial release, leading Paramount to reconsider their investment in documentary filmmaking.

- Flaherty brought his own children to live in Samoa during filming, believing this would help him better understand family dynamics in traditional societies.

- The tattooing sequence required extensive preparation and was performed by traditional Samoan tattoo artists who were reluctant to participate initially.

- The film was shot in 1924 but not released until 1926 due to extensive editing and Flaherty's perfectionism.

- Unlike 'Nanook of the North', 'Moana' received less censorship controversy as it focused more on cultural practices than survival struggles.

- The original camera negative was lost for decades, with surviving prints coming from later distribution copies.

What Critics Said

Upon its release in 1926, 'Moana' received mixed but generally respectful reviews from critics. The New York Times praised its 'extraordinary beauty' and Flaherty's 'sensitive handling of his material,' while Variety noted its 'artistic merit' but questioned its commercial appeal. John Grierson's famous review in the New York Sun hailed it as a new form of cinema, coining the term 'documentary' and praising Flaherty's ability to 'capture the drama of everyday life.' However, some critics found the film slow-paced compared to conventional narrative films. In subsequent decades, critical opinion has become more complex. While still admired for its visual beauty and historical importance, modern critics have questioned Flaherty's staging of scenes and his romanticized portrayal of Samoan life. The film is now recognized as both a pioneering documentary and a problematic example of Western gaze on indigenous cultures. Contemporary scholars debate whether Flaherty preserved a record of disappearing traditions or created a colonial fantasy. Despite these controversies, the film remains a landmark in cinema history, regularly included in lists of the most important documentaries ever made.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary audience reception to 'Moana' was disappointing to its producers. Unlike the surprise success of 'Nanook of the North,' 'Moana' failed to find a wide audience upon its initial release. General audiences of the 1920s, accustomed to dramatic narrative films, found the pacing slow and the lack of conventional plot challenging. The film performed poorly at the box office, leading Paramount to reconsider their investment in documentary filmmaking. However, it did find appreciation among more educated viewers interested in travel, anthropology, and artistic cinema. Small but dedicated audiences appreciated its visual beauty and exotic subject matter. In the decades since, as documentary filmmaking has become more established and audiences more sophisticated, 'Moana' has found renewed appreciation among film enthusiasts, students of cinema history, and documentary filmmakers. Today, it is primarily viewed in academic settings, film archives, and specialized cinema venues rather than by general audiences. Its reputation has grown over time as its historical significance has become more widely recognized.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Nanook of the North (1922)

- Travel literature of the 19th century

- Anthropological studies of Pacific cultures

- Paintings of Paul Gauguin

- Colonial expedition photography

- Ethnographic writings about Samoa

This Film Influenced

- Man of Aran (1934)

- Tabu (1931)

- The Silent World (1956)

- Nanook Revisited (1990)

- Grass: A Nation's Battle for Life (1925)

- The Inheritors (1970)

- The Ax Fight (1975)

- The Last Wave (1977)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of 'Moana' is precarious but not hopeless. The original camera negative, shot on nitrate stock, has been lost, likely due to the inherent instability of nitrate film. However, several 35mm nitrate prints survived in various archives, including the Museum of Modern Art and the British Film Institute. A major restoration was undertaken in the 1970s using the best available elements, though quality varies due to the source materials. More recently, The Criterion Collection released a digitally restored version in 2014, sourced from the best surviving 35mm elements. The restoration work has been complicated by nitrate decomposition and the wear on surviving prints. Some sequences show significant deterioration, while others remain remarkably clear. The film is considered at-risk but not lost, with ongoing preservation efforts by major film archives. The restoration has made the film accessible to modern audiences while preserving this important work of cinema history.