Nanook of the North

"A Drama of Life in the Actual Arctic"

Plot

Nanook of the North follows the daily life and struggles of Nanook, an Inuit hunter, and his family as they navigate the brutal Arctic landscape of northern Quebec. The film documents their remarkable survival techniques, including building igloos, hunting walrus and seal, fishing through ice, and trading at a Hudson's Bay Company post. Throughout their journey, the family faces numerous challenges from starvation to blizzards, demonstrating incredible ingenuity and resilience in one of Earth's most inhospitable environments. The narrative captures both tender family moments and dramatic hunting sequences, painting a portrait of a people perfectly adapted to their extreme surroundings while simultaneously highlighting the encroaching influence of modern civilization on their traditional way of life.

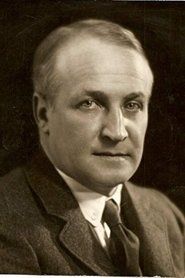

Director

About the Production

Filmed over 16 months between 1920-1921. Flaherty used a hand-cranked camera that frequently froze in the extreme cold. The production team lived alongside the Inuit subjects, building relationships that lasted years. Many scenes were staged for dramatic effect, including the famous walrus hunt and the igloo building sequence. Flaherty insisted on authentic Inuit clothing and tools, though some were outdated even then. The crew had to develop their film in makeshift darkrooms and transport equipment by dog sled across hundreds of miles of frozen terrain.

Historical Background

Nanook of the North emerged in the post-World War I era when audiences were hungry for authentic experiences and escape from modern industrial life. The 1920s saw a surge of interest in anthropology and ethnography, with Western societies fascinated by 'primitive' cultures they believed were disappearing. The film was created during the height of colonial expansion, when Indigenous peoples were often viewed through a romanticized lens. The Arctic regions were undergoing rapid change due to increased contact with Western traders, missionaries, and government officials, making traditional ways of life increasingly difficult to maintain. The film's release coincided with the golden age of silent cinema, when visual storytelling reached its artistic peak. It also predated the establishment of documentary ethics and standards, allowing filmmakers considerable freedom in how they presented their subjects.

Why This Film Matters

Nanook of the North revolutionized filmmaking by essentially creating the feature-length documentary genre and establishing many conventions that would define documentary cinema for decades. It introduced the concept of observational filmmaking, though with significant staging, and demonstrated that documentaries could be both educational and commercially successful. The film created enduring stereotypes about Inuit people while also generating unprecedented sympathy and interest in Indigenous cultures. It sparked ongoing debates about documentary ethics that continue today, particularly regarding the balance between authenticity and dramatic storytelling. The film's success proved that audiences would embrace non-fiction storytelling, paving the way for future documentarians like Dziga Vertov and later the Direct Cinema movement. Its influence extends to reality television and modern documentary series that blend observation with narrative construction.

Making Of

Robert Flaherty originally traveled to the Arctic as an explorer and prospector, bringing along a camera to document his journeys. After his first expedition's footage was destroyed, he secured funding from fur trading company Revillon Frères to return and make a proper film. Flaherty developed a unique collaborative approach, working closely with the Inuit to determine what aspects of their lives to film and how to present them. He lived with the community for over a year, learning their language and customs. The production faced extreme challenges: cameras freezing in temperatures reaching -40°C, film becoming brittle in the cold, and the constant threat of starvation for both crew and subjects. Flaherty insisted on multiple takes for many scenes, a revolutionary approach for documentary filmmaking at the time. The relationship between Flaherty and his subjects was complex - while he genuinely respected them, he also manipulated scenes for dramatic effect, creating an ongoing ethical debate about documentary authenticity.

Visual Style

The cinematography was groundbreaking for its time, achieved under incredibly difficult conditions. Flaherty used a hand-cranked Bell & Howell camera that frequently malfunctioned in the extreme cold, requiring constant maintenance. The crew developed special techniques to prevent equipment from freezing, including keeping cameras inside their clothing when not filming. The film features remarkable wide shots of the Arctic landscape that emphasize both its beauty and its overwhelming scale. Close-ups of faces and hands during hunting scenes create intimacy and tension. The famous igloo-building sequence required cutting a special igloo with an ice window to allow enough light for filming. The black and white photography creates stark contrasts between snow, sky, and human figures, enhancing the visual drama. Despite technical limitations, the film achieves a level of visual poetry that elevates it beyond simple documentation.

Innovations

Nanook of the North pioneered numerous technical innovations in documentary filmmaking. Flaherty developed new methods for filming in extreme cold, including modified camera housings and special film handling techniques. The film was one of the first to use multiple camera angles in a documentary context, particularly during the hunting sequences. The igloo interior shots required innovative lighting solutions using reflected sunlight through ice windows. Flaherty experimented with time-lapse photography to show the changing Arctic light. The film's editing techniques, particularly the cross-cutting between different hunting activities, established narrative conventions for documentary storytelling. The production also developed new methods for transporting and storing film equipment in Arctic conditions. These technical achievements were particularly remarkable given that Flaherty was largely self-taught as a filmmaker.

Music

As a silent film, Nanook of the North was originally accompanied by live musical performances during theatrical screenings. The recommended score included classical pieces by composers like Smetana and traditional folk music. Different theaters created their own musical interpretations, with some using Inuit-inspired compositions while others opted for conventional dramatic music. In 1999, a new orchestral score was composed by Timothy Brock, incorporating Inuit musical elements while maintaining the film's dramatic tension. Modern restorations have included various musical accompaniments, ranging from minimalist ambient scores to full orchestral arrangements. The absence of synchronized sound actually enhances the film's documentary quality, forcing viewers to focus on the visual storytelling and natural sounds of the Arctic environment.

Famous Quotes

Nanook, with the patience of a fisherman, waits for the seal to come up for air.

The great white silence, a silence so profound that it becomes a presence in itself.

In this land of endless ice and snow, life is measured not in years, but in successful hunts.

The igloo, home of the North, built with nothing but snow blocks and the wisdom of generations.

Memorable Scenes

- The iconic igloo-building sequence where Nanook and his family construct their snow home in time-lapse, showcasing remarkable architectural skill and teamwork

- The dramatic walrus hunt on the ice floes, where Nanook and his fellow hunters struggle with the massive animal using traditional harpoons

- The gramophone scene where Nanook curiously examines the modern device, biting the record in confusion and wonder

- The seal hunting scene through a small ice hole, demonstrating the patience and precision required for Arctic survival

- The family huddled together in their igloo as a blizzard rages outside, emphasizing the warmth of human connection against nature's fury

Did You Know?

- The subject 'Nanook' was actually named Allakariallak, a respected Inuit hunter who was already familiar with modern technology including rifles and gramophones

- The famous scene showing Nanook listening to a gramophone and biting the record was completely staged - Allakariallak had seen gramophones before and was merely acting confused for the camera

- Flaherty accidentally burned all his original footage from a 1916 expedition when a cigarette dropped on the film cans, forcing him to start over from scratch

- The igloo in the film was specially built with a cutaway side and ice window to allow filming inside - real igloos were typically much smaller and darker

- Despite portraying traditional life, many of the hunting techniques shown were already outdated by the 1920s, as most Inuit had adopted rifles instead of harpoons

- Allakariallak died of starvation two years after the film's release during a severe winter, highlighting the very real dangers depicted in the documentary

- The film was sponsored by Revillon Frères, a French fur trading company, which partly explains its focus on traditional hunting methods

- Flaherty paid his Inuit subjects with food and supplies rather than money, as they had little use for currency in their traditional economy

- The original negative was thought lost for decades but was discovered in the 1960s in a Dutch archive

- The film's success inspired a wave of 'exotic' documentaries throughout the 1920s and 1930s, though few matched its artistic quality

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics hailed Nanook of the North as a groundbreaking masterpiece, with The New York Times calling it 'a beautiful and moving picture of human life in one of the most remote corners of the earth.' Critics praised its technical achievements in extreme conditions and its emotional power. However, even in 1922, some reviewers questioned the authenticity of certain scenes. Modern criticism is more divided - while acknowledging the film's historical importance and artistic merit, contemporary critics often criticize its staging, romanticization, and colonial perspective. The film is now frequently studied in film schools as both a pioneering achievement and a cautionary tale about documentary ethics. Many modern Inuit and Indigenous critics have pointed out how the film created stereotypes that have affected how their cultures are portrayed for a century.

What Audiences Thought

Nanook of the North was a commercial and critical success upon its release, playing for months in major cities around the world. Audiences were fascinated by the exotic subject matter and the film's dramatic presentation of Arctic life. Many viewers believed they were watching completely authentic footage, which added to the film's impact. The human element - particularly the family dynamics and Nanook's personality - resonated strongly with viewers. The film's success proved that documentaries could attract mainstream audiences, not just specialized or educational viewers. However, modern Inuit audiences often have mixed feelings about the film, appreciating the documentation of their ancestors' skills while criticizing the misrepresentations and staged elements.

Awards & Recognition

- Photoplay Magazine Medal of Honor (1922)

- National Board of Review Award - One of the Top Ten Films of 1922

Film Connections

Influenced By

- In the Land of the Head Hunters (1914) by Edward S. Curtis

- Early ethnographic photography and films

- Flaherty's own experiences as an Arctic explorer

- Travelogue films of the 1910s

- Silent era dramatic filmmaking techniques

This Film Influenced

- Man of Aran (1934) by Robert Flaherty

- Louisiana Story (1948) by Robert Flaherty

- The Silent World (1956) by Jacques Cousteau

- Koyaanisqatsi (1982) by Godfrey Reggio

- March of the Penguins (2005) by Luc Jacquet

- The White Diamond (2004) by Werner Herzog

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by the Library of Congress and selected for the National Film Registry in 1989 for its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance. Multiple restoration efforts have been undertaken, most notably by the Museum of Modern Art in the 1970s and more recently by Criterion Collection. The original camera negative was discovered in excellent condition in the Netherlands in the 1960s, allowing for high-quality restorations. The film exists in complete form and is regularly screened at film archives and museums worldwide. Digital restorations have been created from the best available 35mm elements, ensuring the film's preservation for future generations.