Dorothy Arzner

Director

About Dorothy Arzner

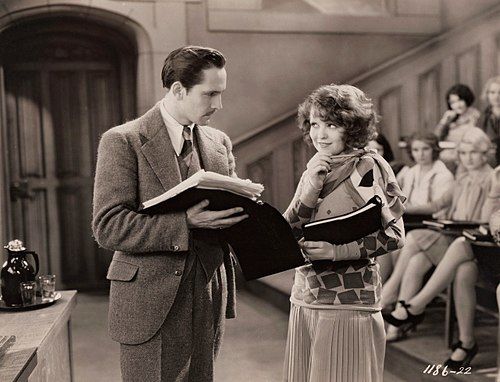

Dorothy Arzner was a pioneering American film director who became the most prolific female director working in Hollywood during the studio system era. Born into a wealthy family in San Francisco, she initially pursued medicine before being drawn to the film industry through her father's restaurant business connections to Hollywood elites. Arzner began her career as a script typist at Paramount Pictures in 1919 and worked her way up through various positions including script clerk, editor, and screenwriter. Her directorial debut came in 1927 with 'Fashions for Women,' and she quickly established herself as a capable director with a distinctive vision. Arzner made history in 1929 by directing 'The Wild Party,' Clara Bow's first sound film, and invented the first boom microphone to solve technical challenges during filming. Throughout her career, she directed 21 films between 1927 and 1943, consistently focusing on strong female protagonists and exploring themes of women's independence, sexuality, and professional ambition. After leaving Hollywood, she became a respected film professor at UCLA and continued to influence generations of filmmakers through her teaching and occasional television work until her death in 1979.

The Craft

Behind the Camera

Arzner's directing style was characterized by her focus on strong, independent female protagonists and her exploration of women's issues including career ambitions, sexuality, and relationships. She employed a naturalistic approach to performance, often drawing out subtle emotional nuances from her actors. Her visual style combined sophisticated camera work with intimate close-ups, and she was particularly adept at handling dialogue scenes in early sound films. Arzner frequently used costumes and set design to reinforce character development and thematic elements, creating visually rich environments that complemented her narratives. Her films often subverted traditional gender roles and challenged conventional morality, making her work distinctly feminist for its time.

Milestones

- First woman to join the Directors Guild of America

- Invented the boom microphone during filming of 'The Wild Party'

- Directed Clara Bow's first talking picture 'The Wild Party' (1929)

- Only female director working in Hollywood during the 1930s

- Taught film at UCLA for many years after retiring from directing

- Received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame

- Directed Katharine Hepburn in 'Christopher Strong' (1933)

Best Known For

Must-See Films

Accolades

Won

- Hollywood Walk of Fame Star (1960)

- Directors Guild of America Honorary Life Member

- Women in Film Crystal Award (1975)

Nominated

- Academy Award nomination for Best Writing (Original Story) for 'Sarah and Son' (1930)

- Venice Film Festival Golden Lion nomination for 'Dance, Girl, Dance' (1940)

Special Recognition

- First woman admitted to the Directors Guild of America

- UCLA Film and Television Archive established the Dorothy Arzner Collection

- Women in Film Pioneer Award (1975)

- National Film Preservation Board selected 'Dance, Girl, Dance' for preservation in the National Film Registry (2007)

Working Relationships

Worked Often With

Studios

Why They Matter

Impact on Culture

Dorothy Arzner's cultural impact extends far beyond her filmography, as she stands as a towering figure in the history of women in cinema. As the only woman directing feature films in Hollywood during the 1930s, she broke through formidable gender barriers in an industry dominated by men. Her films consistently centered women's experiences and perspectives, offering audiences complex female characters who defied traditional stereotypes. Arzner's work challenged the restrictive Hays Code through subtle but powerful commentary on women's sexuality and independence. Her technical innovation with the boom microphone revolutionized sound recording in cinema. Beyond her own films, Arzner's success paved the way for future generations of women directors, and her later teaching career at UCLA allowed her to directly influence aspiring filmmakers. Her films, particularly 'Dance, Girl, Dance,' have been rediscovered by feminist film scholars and are now recognized as important contributions to feminist cinema.

Lasting Legacy

Dorothy Arzner's legacy is that of a trailblazer who created opportunities for women in an industry that systematically excluded them from creative leadership roles. Her films have been reassessed by contemporary scholars as important feminist texts that offered sophisticated critiques of gender roles and social expectations. The Dorothy Arzner Collection at UCLA preserves her papers, scripts, and films, ensuring that future generations can study her work. Film schools worldwide teach her techniques and analyze her films as examples of early feminist filmmaking. The Directors Guild of America honors her memory through the Dorothy Arzner Award, recognizing outstanding achievement by women in directing. Her life story has inspired numerous documentaries, books, and academic studies about women in film history. Arzner's ability to maintain creative control and artistic integrity while working within the restrictive studio system serves as a model for independent filmmakers today. Her rediscovered films continue to be screened at film festivals and retrospectives, introducing new audiences to her distinctive vision and contribution to cinema history.

Who They Inspired

Dorothy Arzner influenced generations of filmmakers through both her body of work and her role as a mentor. Her focus on strong female characters inspired later feminist directors including Agnès Varda, Chantal Akerman, and Sofia Coppola. The technical innovations she pioneered, particularly in sound recording, influenced industry standards. Her ability to work within the studio system while maintaining artistic independence inspired directors like John Cassavetes and independent filmmakers who followed. At UCLA, she directly taught future industry leaders including Francis Ford Coppola, who has acknowledged her influence on his understanding of film direction. Her films' exploration of women's professional ambitions and personal conflicts prefigured themes that would become central to later women's cinema. Contemporary directors like Greta Gerwig and Kelly Reichardt have cited Arzner as an important influence in interviews. Her success in creating commercially viable films with feminist themes demonstrated that such content could find audiences, encouraging studios to take more risks on women's stories. The Dorothy Arzner Directing Award, established by Women in Film, continues to honor her legacy by supporting emerging women directors.

Off Screen

Dorothy Arzner never married and lived openly as a lesbian during a time when such relationships were heavily stigmatized in Hollywood. She maintained a long-term relationship with choreographer and dancer Marion Morgan from the 1920s until Morgan's death in 1971. The couple lived together in a home in the Hollywood Hills, which became a gathering place for artistic and intellectual circles. Arzner was known for her sharp wit, independence, and refusal to conform to gender expectations. She was an avid tennis player and maintained strong friendships with many Hollywood actresses, including Katharine Hepburn and Joan Crawford. Despite her sexuality, she navigated the studio system successfully and maintained professional relationships with studio executives throughout her career.

Education

Attended the University of Southern California (USC) where she studied medicine before transferring to Stanford University; later attended film classes at USC

Did You Know?

- She was the first woman to direct a talking picture in Hollywood

- She invented the first boom microphone by attaching a microphone to a fishing rod

- She was the only woman member of the Directors Guild of America for many years

- She turned down an offer from Disney to direct 'Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs'

- She was a skilled tennis player who competed in tournaments

- She wore tailored suits and ties, challenging gender norms in her era

- Her film 'Dance, Girl, Dance' was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in 2007

- She directed 21 feature films, more than any other woman of her era

- She was known for giving actresses more creative input than other directors

- She temporarily left directing in 1943 due to health issues but continued working in television

- Her home in the Hollywood Hills was a gathering place for Hollywood's artistic community

- She was one of the few directors who successfully transitioned from silent films to talkies

In Their Own Words

I don't think a woman has to be a man to be a director. She has to be a woman director.

I never had any trouble with men in the studio system. I just did my work and they did theirs.

The thing that makes a picture is the story. If you haven't got a story, you haven't got anything.

I was a feminist before the word was invented.

I think women make the best directors because they're more sensitive to people's feelings.

I never wanted to be a man. I wanted to be a director.

The camera is a very honest instrument. It doesn't lie.

I always tried to make pictures about women who were trying to find themselves.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Dorothy Arzner?

Dorothy Arzner was a pioneering American film director who became the most prolific female director working in Hollywood during the studio system era. She directed 21 feature films between 1927 and 1943 and was the only woman directing feature films in Hollywood during the 1930s. Arzner was known for her focus on strong female characters and her technical innovations in early sound cinema.

What films is Dorothy Arzner best known for?

Arzner's most famous films include 'The Wild Party' (1929), Clara Bow's first talking picture; 'Christopher Strong' (1933) starring Katharine Hepburn; 'Dance, Girl, Dance' (1940) with Lucille Ball and Maureen O'Hara; 'Sarah and Son' (1930); 'Merrily We Go to Hell' (1932); and 'Craig's Wife' (1936). Her films are celebrated for their feminist themes and complex female characters.

When was Dorothy Arzner born and when did she die?

Dorothy Arzner was born on January 3, 1897, in San Francisco, California, and died on October 1, 1979, in La Jolla, California, at the age of 82. She lived through the entire golden age of Hollywood and witnessed the transition from silent films to sound cinema.

What awards did Dorothy Arzner win?

While Arzner never won an Academy Award, she received significant recognition including a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960, the Directors Guild of America Honorary Life Membership, and the Women in Film Crystal Award in 1975. Her film 'Sarah and Son' earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Story, and 'Dance, Girl, Dance' was nominated for the Golden Lion at Venice.

What was Dorothy Arzner's directing style?

Arzner's directing style focused on strong, independent female protagonists and explored themes of women's independence, sexuality, and professional ambition. She employed naturalistic performances, sophisticated camera work, and was particularly skilled at handling dialogue in early sound films. Her visual style combined intimate close-ups with rich set designs, and she frequently used costumes to reinforce character development and thematic elements.

Learn More

Films

2 films