The Wild Party

"She was the life of every party... until the party became her life!"

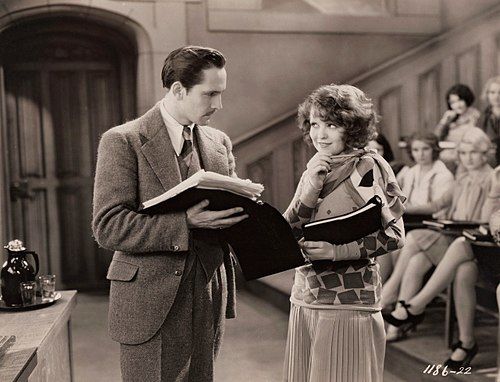

Plot

Stella Ames is a vivacious college student who prioritizes wild parties and social life over her academic responsibilities at a women's college. When she and her friends venture to a local speakeasy, Stella finds herself in a precarious situation that requires rescue from her handsome and principled professor, James Gilmore. The incident sparks malicious gossip across campus about an inappropriate relationship between the student and teacher, threatening both their reputations. As rumors escalate and the college administration becomes involved, Stella must navigate the social fallout while discovering her own moral compass. Ultimately, she proves her character by protecting another innocent student from scandal, earning the respect of Professor Gilmore and demonstrating that beneath her party-girl exterior lies a woman of substance and integrity.

About the Production

This was one of Dorothy Arzner's early directorial efforts and showcased her ability to handle both dramatic and comedic elements. The film was produced during the challenging transition from silent to sound cinema, requiring actors to adapt to new recording technologies. Clara Bow, known as the 'It Girl,' was at the peak of her popularity, though her Brooklyn accent initially posed challenges for sound recording. The production team had to work around early sound equipment limitations, which restricted camera movement and required actors to remain relatively stationary during dialogue scenes.

Historical Background

The Wild Party was released during a pivotal moment in American history and cinema. 1929 marked the end of the Roaring Twenties and the beginning of the Great Depression, which would soon transform Hollywood's output and audience preferences. The film captured the last gasp of the flapper era and the Jazz Age's hedonistic spirit before the economic crash altered cultural values. In terms of film history, this was during the chaotic transition from silent films to talkies, a period that saw many silent stars' careers end while new talents emerged. The Hays Code, though not yet fully enforced, was beginning to influence content, making the film's relatively daring themes notable. The stock market crash occurred just months after the film's release, making its depiction of carefree youth and party culture seem almost nostalgic from a pre-Depression America.

Why This Film Matters

The Wild Party represents an important milestone in cinema history as one of the early sound films directed by a woman, Dorothy Arzner, who would become the most prolific female director of her era. The film encapsulates the flapper culture of the 1920s, documenting the changing social mores regarding women's behavior, education, and independence. It also reflects the public's fascination with college life, which was becoming increasingly accessible to women. Clara Bow's performance in this film helped bridge the gap between silent and sound cinema, proving that personality and charisma could transcend technological changes. The movie's exploration of gossip, reputation, and moral judgment in academic settings remains relevant, while its depiction of student-teacher dynamics was progressive for its time. Arzner's direction demonstrated that women could handle complex dramatic material and guide major stars, paving the way for future female filmmakers.

Making Of

Dorothy Arzner faced significant challenges as a female director in male-dominated Hollywood. During filming, she had to assert her authority constantly, particularly with male crew members who were initially resistant to taking direction from a woman. Clara Bow struggled with the transition to sound, suffering from microphone anxiety that required multiple takes for some scenes. The production utilized early sound-on-film technology, which was cumbersome and limited the actors' mobility. Arzner worked closely with the sound engineers to develop techniques that would allow for more natural performances. The film's college setting was created on Paramount's backlot, with attention to period detail in costumes and props to reflect 1920s campus life. There were tensions on set between Bow and March initially, as March was intimidated by Bow's superstar status, but they eventually developed a professional rapport that translated to their on-screen chemistry.

Visual Style

The film's cinematography by Charles Lang reflects the technical constraints and aesthetic of early sound cinema. The camera work is relatively static compared to silent films, as early sound recording equipment limited mobility. Lang employed careful lighting techniques to compensate for the less sensitive film stock required for sound recording, creating dramatic contrasts that enhanced the emotional tone of key scenes. The party sequences utilize more dynamic camera angles and movement, suggesting the energy and chaos of college social life. Lang's use of close-ups, particularly on Clara Bow, helped convey emotion in ways that silent film acting couldn't achieve. The cinematography effectively captures the Art Deco influences in set design and the fashionable clothing of the flapper era, creating a visually authentic representation of 1920s college life.

Innovations

The Wild Party showcased several technical innovations for its time, particularly in sound recording. Dorothy Arzner pioneered the use of what would become the boom microphone during this period, allowing for greater flexibility in actor movement and more natural sound capture. The film employed early sound-on-film technology rather than the competing sound-on-disc systems, which provided better synchronization between picture and audio. The production team developed techniques to minimize the visual intrusion of microphones, using creative set design and camera angles to hide recording equipment. The film's successful integration of music, dialogue, and sound effects demonstrated the growing sophistication of sound cinema in 1929. These technical achievements were particularly impressive given that the film was made less than two years after the first feature-length talkie revolutionized the industry.

Music

The Wild Party featured a musical score by John Leipold, Paramount's house composer, who specialized in early sound film music. The soundtrack incorporated popular jazz tunes of the era, reflecting the film's party atmosphere and youthful energy. As an early talkie, the film utilized synchronized music and sound effects, with some scenes featuring diegetic music from radios or live performances at the parties. The sound quality was typical of 1929 productions, with occasional technical limitations including some background hiss and limited dynamic range. The film's theme music was later released as sheet music, capitalizing on the movie's popularity. The sound design included innovative uses of ambient noise to create realistic party atmospheres, though these had to be carefully balanced with dialogue recording challenges of the period.

Did You Know?

- Dorothy Arzner was the only woman director working in Hollywood during the late 1920s and early 1930s

- This was Clara Bow's first sound film, testing whether her silent film popularity would translate to talkies

- The film was originally titled 'The Wild Party' but was briefly changed to 'The Party Girl' before reverting to the original title

- Fredric March was relatively unknown at the time, and this film helped launch his leading man career

- The movie was filmed in just 24 days, typical for the rapid production schedules of the era

- Paramount was initially hesitant about Arzner directing due to her gender, but relented after she proved herself on previous projects

- The film's theme of college life and student-teacher relationships was considered controversial for 1929

- Clara Bow's real-life reputation as a party girl was heavily leveraged in the film's marketing

- The bar scenes were carefully censored to comply with the Hays Code, which was beginning to be enforced

- Dorothy Arzner invented the first boom microphone during this period to improve sound quality on her sets

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its energetic pace and Clara Bow's magnetic screen presence, with Variety noting that she 'proves she can talk as well as she can act.' The New York Times appreciated the film's modern sensibility and Arzner's deft handling of the material, though some reviewers felt the plot was somewhat conventional. Critics were particularly impressed with how well Bow transitioned to sound, given the difficulties many silent stars faced. Fredric March's performance was noted as promising, with several reviewers predicting a bright future for the newcomer. Modern film historians have reevaluated The Wild Party as an important example of early sound cinema and a significant work in Dorothy Arzner's filmography, appreciating its feminist undertones and commentary on double standards.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1929 responded enthusiastically to The Wild Party, drawn primarily by Clara Bow's immense popularity and the novelty of hearing her speak on screen. The film performed well at the box office, particularly in urban areas where college life and flapper culture resonated with young viewers. Many audience members appreciated the film's mix of comedy, drama, and romance, which was typical of the era's entertainment preferences. The party sequences and jazz music elements were especially popular, capturing the spirit of the age. However, some more conservative viewers found the film's themes slightly scandalous, particularly the suggestion of impropriety between a student and professor. Despite these concerns, the film's ultimate moral resolution satisfied most viewers, and it helped cement Bow's status as a viable sound-era star.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The 'flapper' films of the late 1920s

- College campus comedies popular in the silent era

- The works of Ernst Lubitsch for their sophisticated social commentary

- Contemporary newspaper stories about college life scandals

- The broader cultural fascination with youth culture in the Roaring Twenties

This Film Influenced

- College films of the 1930s

- Later Dorothy Arzner films dealing with strong female protagonists

- The 'bad girl with a heart of gold' trope in subsequent films

- Academic romance films of the sound era