An Adventurous Automobile Trip

Plot

A group of travelers in Paris become frustrated when they learn that a train journey to Monte Carlo will take 17 hours. They encounter an inventor who offers them a special automobile that promises to reach their destination in just two hours. The journey quickly transforms into a fantastical adventure as the car takes flight, travels underwater, and encounters numerous magical obstacles and surreal situations along the way. The travelers face increasingly bizarre complications, including encounters with giant sea creatures, celestial bodies, and various mechanical failures that showcase Méliès' signature special effects. The film culminates in a chaotic but ultimately successful arrival at Monte Carlo, demonstrating the triumph of imagination over conventional travel limitations.

Director

About the Production

This film was one of Méliès' most ambitious productions, featuring complex mechanical props, multiple set changes, and sophisticated special effects. The automobile was a specially constructed prop that could be manipulated to appear flying and underwater. Méliès employed multiple exposure techniques, substitution splices, and dissolves to create the magical effects. The production required extensive painted backdrops and stage machinery to simulate the various fantastical environments.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the golden age of early cinema, a period when filmmakers were experimenting with the possibilities of the new medium. 1904 was a pivotal year in cinema history, with the industry transitioning from simple actualities to complex narrative films. The early 1900s also saw the rise of automobile culture, with cars becoming symbols of modernity and progress. This film reflects contemporary fascination with technological advancement and the spirit of exploration that characterized the Belle Époque era. The journey to Monte Carlo was particularly relevant as the destination had recently become synonymous with luxury gambling and European sophistication. Méliès' work also coincided with the development of film as an international industry, with his films being distributed globally through the Star Film Company's extensive network.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents a crucial milestone in the development of narrative cinema and special effects techniques. Méliès' innovative use of multiple exposure, substitution splices, and elaborate set design influenced generations of filmmakers and established many conventions of the fantasy and science fiction genres. The film's combination of comedy, adventure, and technical spectacle demonstrated cinema's potential as a medium for imaginative storytelling beyond simple documentation. Its success helped establish the viability of longer narrative films and contributed to the development of film as a commercial art form. The film also reflects the early 20th century's optimism about technology and progress, themes that would continue to resonate throughout cinema history. Méliès' work in this film and others laid the groundwork for the special effects industry and influenced pioneers like Edwin S. Porter and D.W. Griffith.

Making Of

The production of 'An Adventurous Automobile Trip' represented the pinnacle of Méliès' technical and artistic achievements in 1904. The film was shot in Méliès' custom-built glass studio in Montreuil-sous-Bois, which allowed for maximum control over lighting and effects. The automobile prop was a marvel of engineering for its time, featuring removable parts and mechanisms that could be manipulated to simulate various states of damage and transformation. Méliès and his team spent weeks constructing the elaborate sets, including the train station, mountain landscapes, and underwater environments. The special effects required multiple exposures, careful masking, and precise timing - all achieved without the benefit of modern editing equipment. The underwater sequence was particularly challenging, requiring actors to hold their breath while being filmed through specially designed glass tanks. Méliès' brother Gaston managed the American distribution, ensuring the film reached audiences across the Atlantic. The hand-coloring process was performed by a team of women workers in a factory-like setting, with each worker responsible for coloring specific colors in each frame.

Visual Style

The cinematography exemplifies Méliès' distinctive visual style, characterized by theatrical staging, elaborate painted backdrops, and innovative camera techniques. The film employs static camera positioning typical of the era, but uses this limitation creatively through complex mise-en-scène and choreographed action within the frame. Méliès utilized multiple exposure techniques to create ghostly effects and magical transformations, while substitution splices allowed for sudden appearances and disappearances. The underwater scenes were filmed through glass tanks with carefully positioned lighting to create the illusion of submersion. The hand-coloring process added visual richness to key scenes, enhancing the fantastical atmosphere. The cinematography demonstrates Méliès' mastery of spatial composition within the constraints of early film technology.

Innovations

The film showcases numerous technical innovations that were groundbreaking for 1904. Méliès employed sophisticated multiple exposure techniques to create the illusion of the automobile flying and traveling underwater. The substitution splice technique was used extensively for magical transformations and sudden appearances. The film's elaborate mechanical props, particularly the automobile, represented significant advances in practical effects design. The underwater filming techniques, using glass tanks and carefully controlled lighting, were particularly innovative for the period. The hand-coloring process, while labor-intensive, demonstrated early approaches to adding color to motion pictures. The film's complex narrative structure, with over 30 distinct scenes, pushed the boundaries of what was possible in terms of storytelling length and complexity in early cinema.

Music

As a silent film, 'An Adventurous Automobile Trip' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The specific musical selections would have varied by venue and performer, but typically included popular songs of the era, classical pieces, and improvisational accompaniment timed to the on-screen action. Larger theaters might have employed small orchestras, while smaller venues used piano or organ accompaniment. The film's fantastical elements would have suggested musical choices ranging from whimsical to dramatic. Modern restorations are often accompanied by newly composed scores that attempt to capture the spirit of early 20th century music while complementing the film's visual style.

Famous Quotes

We shall reach Monte Carlo in two hours!

The train takes seventeen hours - impossible!

My automobile can do the impossible!

Through the air and under the sea!

Memorable Scenes

- The automobile taking flight from the Paris streets

- The underwater sequence with giant sea creatures

- The car's transformation and repair during the journey

- The arrival in Monte Carlo with the damaged but victorious automobile

- The initial scene at the train station where the travelers learn about the long journey time

Did You Know?

- This film was one of the longest and most expensive productions of its time, costing approximately 37,500 francs

- The film was released in America by the Edison Manufacturing Company under the title 'An Impossible Voyage'

- Méliès himself appears in the film as one of the travelers, continuing his tradition of acting in his own productions

- The automobile prop was designed to be disassembled and reassembled to create the illusion of transformation and damage

- The underwater sequence was achieved by filming through a glass tank filled with water and smoke

- The film contains over 30 different scenes, making it one of the most complex early narrative films

- Star Film catalog number 655-657, indicating it was a significant production in Méliès' catalog

- The film's original French title was 'Le Voyage à travers l'impossible' (Voyage Through the Impossible)

- Some scenes were hand-colored frame by frame, a laborious process that Méliès employed for his premium productions

- The Monte Carlo destination was chosen because it represented luxury and sophistication to contemporary audiences

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's technical achievements and imaginative vision, with trade publications highlighting its spectacular effects and elaborate production values. The film was particularly noted for its length and complexity, which set it apart from the shorter films typical of the period. Modern critics and film historians recognize it as one of Méliès' masterpieces, citing its sophisticated special effects and ambitious narrative structure. The film is often studied as an example of early cinema's transition from simple novelty to complex storytelling. Critics have noted how Méliès' theatrical background influenced the film's staging and visual style, creating a unique cinematic language that blended stage techniques with the possibilities of the new medium.

What Audiences Thought

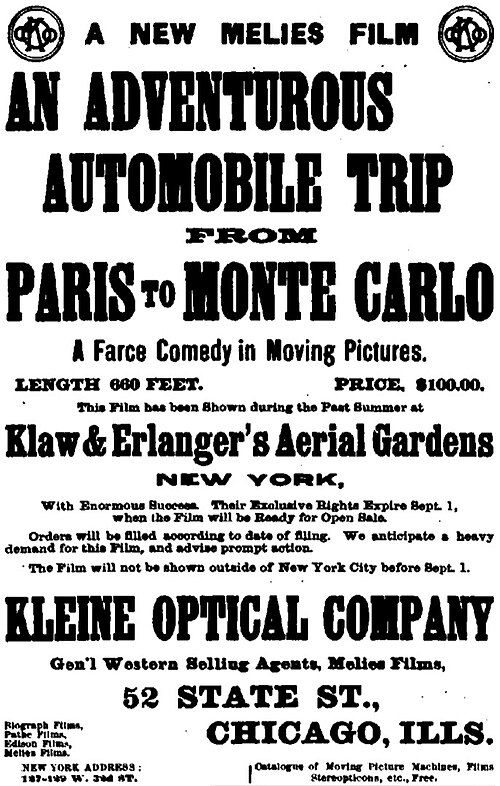

The film was enormously popular with audiences both in France and internationally, particularly in the United States where it was distributed by Edison. Audiences were captivated by the magical effects and fantastical journey, which represented the cutting edge of cinematic entertainment. The film's length and complexity were seen as value for money by theater owners and audiences alike. Contemporary reports describe audiences reacting with wonder and applause to the special effects sequences, particularly the flying automobile and underwater scenes. The film's success helped cement Méliès' reputation as a master of cinematic magic and contributed to the growing popularity of fantasy and science fiction films in the early 1900s.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Jules Verne's adventure novels

- H.G. Wells' science fiction

- Stage magic traditions

- Georges Méliès' earlier films including 'A Trip to the Moon'

- Contemporary fascination with automobile technology

This Film Influenced

- The Great Train Robbery (1903)

- The Impossible Voyage (1904) remakes

- Modern fantasy and adventure films

- Early science fiction cinema

- Surrealist films of the 1920s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in multiple copies and has been preserved by various film archives including the Cinémathèque Française and the Museum of Modern Art. Several versions exist, including both black-and-white and hand-colored prints. The film has been digitally restored and is available on various home video releases and streaming platforms dedicated to classic cinema.