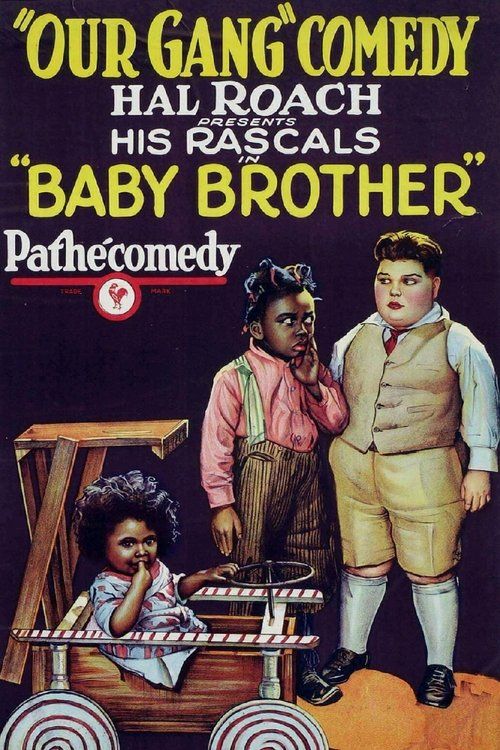

Baby Brother

"The Gang's Greatest Baby Deal!"

Plot

Wealthy young Joe Cobb desperately wants a baby brother to play with, so his nursemaid takes him to the working-class neighborhood where he meets the Our Gang kids. Joe offers three dollars for a baby, prompting Farina to find an African-American neighbor's infant, paint the baby white with flour, and sell it to Joe. Meanwhile, the rest of the gang has established an elaborate assembly-line system for baby care, with different stations for washing, drying, rocking, and feeding both male and female babies. Chaos ensues when the baby's true identity is revealed and the gang's baby-care operation spirals out of control.

About the Production

Filmed during the transition period when Hal Roach was expanding the Our Gang series. The production utilized the studio's standing sets representing working-class neighborhoods. The baby painting scene, while controversial by modern standards, was filmed using edible white flour and was carefully supervised to ensure child safety.

Historical Background

Released in 1927, 'Baby Brother' emerged during the height of the Roaring Twenties, a period of economic prosperity and social change in America. The film reflected contemporary attitudes toward class differences, as evidenced by Joe Cobb's wealth contrasted with the working-class gang. This was also a pivotal year in cinema history, as 'The Jazz Singer' would soon revolutionize the industry with sound. The Our Gang series itself represented a progressive vision of childhood integration, showing children of different backgrounds playing together, though some elements like the baby painting scene now appear dated and problematic by modern standards.

Why This Film Matters

'Baby Brother' represents an important artifact of American popular culture from the silent era, showcasing the Our Gang series' unique approach to children's entertainment. The series was revolutionary in its time for featuring a diverse cast of children playing together naturally, challenging the racial segregation common in 1920s America. However, the film also serves as a reminder of the racial insensitivities of the period, particularly in scenes involving Farina and the baby painting sequence. The Our Gang shorts influenced generations of children's programming and established many tropes still seen in family entertainment today.

Making Of

The production of 'Baby Brother' followed Hal Roach's typical approach to Our Gang shorts, allowing children significant creative freedom within structured scenarios. Director Robert A. McGowan, known for his ability to work with child actors, often captured spontaneous moments of genuine comedy. The baby painting sequence required multiple takes as the child actors found the situation genuinely amusing. The assembly-line sequence was choreographed to maximize physical comedy while ensuring the safety of all infant performers. The film was shot quickly, as most Our Gang shorts were completed in 2-3 days of filming, with extensive use of natural lighting on the studio's outdoor sets.

Visual Style

The film employs standard silent era cinematography techniques typical of Hal Roach productions. The visual style features static medium shots with occasional close-ups for emotional emphasis. The outdoor scenes utilize natural lighting to create a warm, authentic feel. The camera work during the assembly-line sequence uses wider shots to capture the chaotic action, while the baby painting scene uses closer framing to highlight the comedic details. The black and white photography creates strong contrasts that enhance the visual comedy.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking technically, the film demonstrates the efficient production methods developed by Hal Roach Studios for comedy shorts. The use of standing sets and rapid filming schedules allowed for economical production without sacrificing quality. The coordination of multiple child actors and infants in the assembly-line sequence required careful planning and execution, showcasing the studio's expertise in managing complex comedic scenarios.

Music

As a silent film, 'Baby Brother' would have been accompanied by live musical performances in theaters. Typical theater orchestras would have used compiled scores featuring popular songs of the era and classical pieces appropriate to the action. The music would have been synchronized to enhance the comedic timing and emotional moments. No original composed score exists for this short, as was common for studio comedy shorts of the period.

Famous Quotes

Joe Cobb: 'I'll give three dollars for a baby brother!'

Farina: 'I got just what you need - fresh and ready!'

Assembly line sequence: Various intertitles describing the baby care process

Memorable Scenes

- The baby painting sequence where Farina transforms the dark-skinned infant into a 'white baby' using flour, the elaborate assembly-line baby care system with each gang member performing specific tasks, Joe Cobb's initial announcement that he wants to buy a baby brother, the chaos that ensues when multiple babies are being cared for simultaneously, the final reveal of the baby's true identity

Did You Know?

- This was one of the early Our Gang shorts featuring Joe Cobb as the wealthy character, a recurring role he played

- The baby painting scene using flour was considered harmless comedy at the time but is now viewed as racially insensitive

- Allen Hoskins (Farina) was one of the original cast members and appeared in more Our Gang shorts than any other actor

- The film was released during the peak of the silent era, just before the transition to sound began

- Jackie Condon, who appears in this film, was one of the few gang members to appear in both silent and sound Our Gang episodes

- Jean Darling was one of the few female members of the gang during this early period

- The assembly-line baby care sequence was a parody of industrialization and mass production common in 1920s America

- Director Robert A. McGowan often worked under the pseudonym Anthony Mack

- This short was part of the 1926-27 season which included 30 Our Gang productions

- The film showcases the gang's signature improvisational style, with many scenes featuring genuine child reactions

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews in trade publications like Variety and The Motion Picture News praised the film's wholesome entertainment value and the natural performances of the child actors. Critics noted the series' consistent ability to generate laughs without resorting to mean-spirited humor. Modern critics and film historians view the shorts as valuable historical documents, though they acknowledge problematic elements reflecting the racial attitudes of the time. The film is generally regarded as a solid example of the Our Gang formula during its peak silent period.

What Audiences Thought

The Our Gang shorts were enormously popular with audiences in the 1920s, with children and adults alike enjoying the natural comedy and relatable childhood scenarios. 'Baby Brother' would have been well-received by theater audiences as part of a typical double bill program. The series developed a loyal following that would sustain it through the transition to sound and continue for decades. Modern audiences often discover these shorts through television reruns and home video, with reactions ranging from nostalgic appreciation to critical examination of dated elements.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Charlie Chaplin's child comedies

- Harold Lloyd's everyday situations

- Fatty Arbuckle's comedy style

- Contemporary vaudeville routines

This Film Influenced

- Later Our Gang shorts

- The Little Rascals television series

- Modern children's ensemble comedies

- Family sitcoms featuring diverse casts

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in 16mm and 35mm prints through various archives. It has been preserved by the UCLA Film and Television Archive and is part of the Library of Congress collection. Several restored versions exist, including those released on home video. The film is not considered lost and is accessible through various classic film collections.