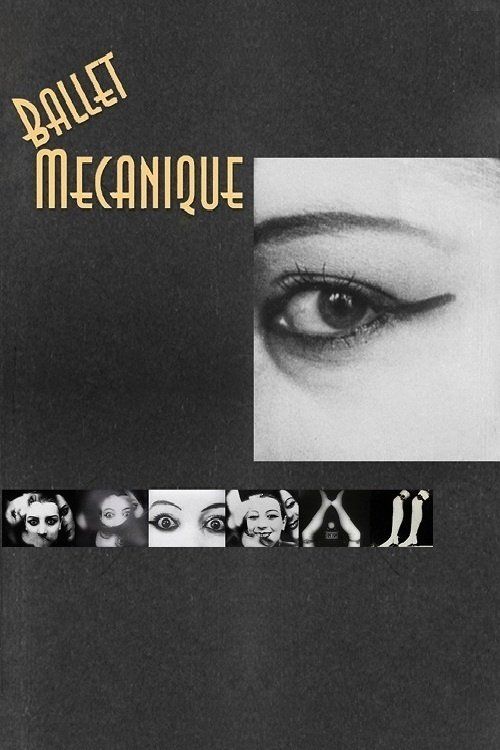

Ballet Mécanique

Plot

Ballet Mécanique is a revolutionary experimental film that presents a dizzying montage of mechanical and abstract imagery, including spinning gears, pistons, kitchen utensils, and geometric shapes. The film alternates between rhythmic, repetitive mechanical movements and brief appearances of human figures, most notably Kiki of Montparnasse whose smiling face and blinking eyes appear among the machines. The visual symphony builds in intensity, creating a hypnotic rhythm through rapid editing and abstract compositions that celebrate the machine age aesthetic. The film culminates in a chaotic explosion of images that blur the line between human and mechanical forms, suggesting the increasing integration of humanity with technology in modern society.

About the Production

Filmed over several months in 1924, the production involved extensive experimentation with camera techniques including slow motion, fast motion, and multiple exposures. The collaboration between Léger and Murphy was often tense, with creative disagreements about the film's direction. The mechanical props were sourced from various Parisian workshops and factories. The film was shot on 35mm film using multiple cameras to achieve the rapid montage effects.

Historical Background

Ballet Mécanique emerged in the aftermath of World War I, during a period of intense artistic experimentation and cultural upheaval in Europe. The 1920s saw the rise of Dadaism and Surrealism, movements that rejected traditional artistic forms and sought to reflect the chaos and disorientation of the modern world. The film was created during the height of the machine age, when industrialization was rapidly transforming society and artists were grappling with humanity's relationship to technology. Paris in the 1920s was the epicenter of the avant-garde, attracting artists from around the world who were pushing the boundaries of their respective mediums. The film reflects the fascination with speed, movement, and mechanical efficiency that characterized the era, while also questioning the dehumanizing aspects of industrialization. This period also saw significant developments in cinema technology, with filmmakers exploring new possibilities for visual expression beyond traditional narrative storytelling.

Why This Film Matters

Ballet Mécanique represents a pivotal moment in the history of cinema, marking the transition from film as mere entertainment to film as an art form capable of abstract expression. Its innovative editing techniques and visual language influenced generations of filmmakers, from Soviet montage theorists to modern music video directors. The film's exploration of the relationship between humans and machines remains remarkably relevant in our increasingly digital age. It helped establish experimental cinema as a legitimate artistic genre and demonstrated the potential of film to create pure visual experiences independent of narrative. The film's aesthetic principles can be seen in everything from industrial design to contemporary digital art. Its restoration and synchronization with Antheil's score in 2000 sparked renewed interest in the relationship between visual and musical abstraction, influencing multimedia artists and installation creators. The film continues to be studied in film schools as a masterpiece of avant-garde cinema and a testament to the revolutionary spirit of the 1920s avant-garde movement.

Making Of

The creation of Ballet Mécanique was a complex collaboration between French painter Fernand Léger and American filmmaker Dudley Murphy, with significant input from composer George Antheil. Léger, influenced by his Cubist background and fascination with industrial machinery, wanted to create a visual symphony that celebrated the machine age. The production involved extensive experimentation with camera techniques including multiple exposures, rapid montage, and rhythmic editing. The mechanical objects used in filming were sourced from Parisian factories and workshops, creating an authentic industrial aesthetic. Kiki of Montparnasse's participation came through her connection to the Paris avant-garde scene, and her brief appearances provided a human counterpoint to the mechanical imagery. The most challenging aspect was the intended synchronization with Antheil's complex musical score, which called for multiple player pianos, percussion instruments, and even airplane propellers. Technical limitations of 1924 made this synchronization impossible, and the film premiered without its intended soundtrack, a fact that frustrated all creators involved.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Ballet Mécanique was revolutionary for its time, employing techniques that were decades ahead of mainstream cinema. The film utilizes rapid montage, multiple exposures, and rhythmic editing to create a visual symphony of mechanical movement. Camera angles and movements were highly experimental, including extreme close-ups, Dutch angles, and tracking shots that emphasized the geometric qualities of mechanical objects. The cinematography deliberately breaks traditional continuity editing, instead creating visual rhythms through repetition and variation. The use of slow motion and fast motion creates temporal distortions that reinforce the film's abstract nature. Lighting techniques were equally innovative, with strong contrasts and silhouettes that emphasized the sculptural qualities of both mechanical and human forms. The cinematographic style directly reflects Léger's Cubist painting background, with its emphasis on geometric forms, multiple perspectives, and the fragmentation of reality. The visual language established in this film would influence countless future works in both experimental and mainstream cinema.

Innovations

Ballet Mécanique achieved numerous technical breakthroughs that would influence cinema for decades. The film pioneered rapid montage techniques, creating rhythmic visual patterns through carefully timed cuts that anticipated music video editing by more than 50 years. It was among the first films to use multiple exposures systematically, layering images to create complex visual compositions. The film's use of slow motion and fast motion in the same sequence was technically innovative for 1924. The cinematography employed extreme close-ups and abstract framing that broke from conventional cinematic language. The film demonstrated early mastery of visual rhythm, using editing as a primary compositional tool rather than merely for narrative continuity. The 2000 restoration project itself was a technical achievement, using digital technology to synchronize the film with Antheil's complex score for the first time. The restoration involved piecing together elements from various archival prints to create the most complete version possible. The film's technical innovations in visual abstraction and rhythmic editing would influence filmmakers from Eisenstein to Godard, and its techniques remain relevant in contemporary digital media.

Music

The original soundtrack was intended to be George Antheil's controversial composition 'Ballet Mécanique,' one of the most radical musical works of the 1920s. Antheil's score called for an unprecedented ensemble of 16 player pianos, xylophones, percussion instruments, and even airplane propellers, creating a mechanical soundscape to match the visual imagery. However, technical limitations of 1924 made synchronization impossible, and the film premiered without music or with improvised accompaniment. The complete score was finally synchronized with the film in 2000 by Paul Lehrman, using modern digital technology to realize the creators' original vision. The synchronized version creates a powerful synthesis of visual and mechanical rhythms, with the music's percussive intensity mirroring the film's visual energy. Antheil's composition itself caused riots at its Paris premiere in 1926, with its relentless mechanical rhythms and unconventional instrumentation shocking audiences. The soundtrack represents one of the earliest attempts at creating a true audiovisual synthesis in cinema, predating similar efforts by decades. The restored version with Antheil's complete score reveals the full artistic intention of the collaboration between Léger, Murphy, and Antheil.

Famous Quotes

The film is a 'ballet of machines' that celebrates the mechanical rhythm of modern life - Fernand Léger

We wanted to create a visual symphony where machines would dance like ballerinas - Dudley Murphy

The cinema is the art of the 20th century, and Ballet Mécanique is its mechanical soul - George Antheil

In Ballet Mécanique, the camera becomes a machine that captures other machines - Contemporary film scholar

This is not a film about machines, but a film that is itself a machine - André Breton

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence of a piston moving in perfect rhythm, establishing the film's mechanical aesthetic

- Kiki of Montparnasse's face appearing among the mechanical objects, her smile and blinking eyes creating a human counterpoint to the machines

- The kaleidoscopic montage of kitchen utensils spinning and colliding in geometric patterns

- The sequence with a human eye blinking in rhythm with mechanical movements, creating an unsettling connection between organic and artificial

- The climactic explosion of abstract shapes and mechanical forms that builds to a frenetic crescendo

- The famous scene of a hat being tossed repeatedly, its arc creating a perfect parabolic curve against geometric backgrounds

- The sequence where mechanical objects appear to dance and interact with human-like movements

- The final montage that combines all previous elements in a chaotic but rhythmic conclusion

Did You Know?

- Originally intended to be accompanied by George Antheil's controversial composition of the same name, but the music was never synchronized with the film in its initial release due to technical limitations

- Kiki of Montparnasse, who appears in the film, was one of the most famous artist's models of the 1920s and Man Ray's primary muse

- The film features a famous sequence with a human eye blinking in rhythm with mechanical movements, creating an unsettling connection between organic and machine

- Dudley Murphy, an American filmmaker, collaborated with Léger but their partnership dissolved after creative disagreements

- The film was banned in several countries for its 'subversive' content and perceived anti-establishment themes

- A restored version with Antheil's complete score was finally realized in 2000, 76 years after the film's creation

- The film influenced the development of music videos and experimental cinema throughout the 20th century

- Léger used techniques learned from his Cubist paintings to create the film's visual style

- The original negative was lost and had to be reconstructed from various prints found in archives worldwide

- The film was part of a larger Dadaist movement that sought to challenge traditional artistic forms and bourgeois values

What Critics Said

Initial critical reception was divided and often hostile, with many mainstream critics dismissing the film as incomprehensible or pretentious. The Parisian press in 1924 largely failed to understand its artistic intentions, with some critics calling it 'a meaningless collection of images' and 'an assault on the senses.' However, avant-garde publications and artists immediately recognized its significance, with publications like L'Esprit Nouveau praising its revolutionary approach. Over time, critical opinion shifted dramatically, and by the 1940s, the film was being recognized as a masterpiece of experimental cinema. Modern critics universally acclaim the film as a groundbreaking work that anticipated many developments in visual culture. The 2000 restoration with Antheil's score received widespread critical praise, with The New York Times calling it 'a revelation that finally realizes the creators' original vision.' Film scholars now consider it one of the most important experimental films ever made, frequently citing it in discussions of cinematic modernism and the relationship between film and other art forms.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reactions were often confused and sometimes hostile, with many viewers walking out of screenings unable to comprehend the film's abstract nature. The lack of narrative structure and rapid, disorienting imagery proved challenging for 1920s audiences accustomed to conventional storytelling. However, the film found enthusiastic supporters among the Parisian avant-garde community, who appreciated its revolutionary approach and artistic ambitions. In subsequent decades, as audiences became more familiar with experimental cinema and abstract art, the film gained a cult following among art house cinema enthusiasts. The 2000 restoration with Antheil's score attracted new audiences, with many younger viewers connecting to its rhythmic energy and visual innovation. Today, the film is primarily viewed in academic settings, art museums, and specialized cinema venues, where audiences generally approach it with an understanding of its historical context and artistic significance. Contemporary audiences often remark on how modern and contemporary the film feels despite being nearly a century old.

Awards & Recognition

- Retrospective recognition at Cannes Classics (2000)

- National Film Registry selection by Library of Congress (2004)

- Avant-garde Film Heritage Award (2005)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Cubist paintings by Picasso and Braque

- Futurist art movement

- Dadaist performance art

- Marcel Duchamp's readymades

- Soviet montage theory

- Abstract animation by Oskar Fischinger

- Man Ray's experimental films

- Ballet Russes productions

- Industrial design of the 1920s

- Jazz music rhythms

This Film Influenced

- Man with a Movie Camera (1929)

- Un Chien Andalou (1929)

- Meshes of the Afternoon (1943)

- Stan Brakhage's experimental films

- Music videos of the 1980s

- Industrial films of the 1930s

- Abstract animation films

- Contemporary digital art installations

- Modern advertising aesthetics

- Computer-generated imagery in cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The original 1924 negative was lost, but the film has been preserved through restoration efforts using various prints from international archives. The most complete restoration was completed in 2000 by the Anthology Film Archives and The Museum of Modern Art, working with Paul Lehrman to synchronize the film with George Antheil's complete score. The restored version was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress in 2004, recognizing its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance. Digital restoration efforts continue to improve the film's visual quality while preserving its original character. The film is considered well-preserved compared to many experimental films of its era, thanks to its recognition as an important work of cinematic art.