Ben Hur

Plot

The 1907 adaptation of Ben-Hur follows the story of Judah Ben-Hur, a Jewish prince from Jerusalem who is betrayed by his childhood friend Messala, a Roman officer. After being falsely accused of an assassination attempt, Ben-Hur is enslaved and his family is imprisoned. During his journey as a galley slave, he witnesses Jesus Christ's crucifixion and experiences a spiritual transformation. The film depicts key moments from the novel including Ben-Hur's suffering aboard the Roman galley, his eventual reunion with his family, and his encounter with Christ, though in this abbreviated 15-minute version, many subplots were condensed or omitted entirely.

Director

About the Production

This was one of the most ambitious productions of its time, requiring location shooting, crowd scenes, and maritime sequences. The galley scenes were particularly challenging to stage in 1907. The production used actual boats and created makeshift sets to simulate ancient Jerusalem. Director Sidney Olcott had to work within the technical limitations of early cinema, including the lack of close-up shots and the bulkiness of cameras.

Historical Background

The 1907 Ben-Hur was produced during a pivotal period in cinema history, often called the 'one-reel era' when films were typically 10-15 minutes long. This was before the feature film became standard, and before Hollywood had emerged as the center of American film production. The nickelodeon boom was in full swing, with thousands of small theaters opening across America. The film industry was still establishing its legal and artistic boundaries, and copyright law had not yet adapted to the new medium of motion pictures. The production of Ben-Hur represented an early attempt to bring serious literary adaptation to the screen, challenging the perception that movies were merely cheap entertainment. The film's release came just two years after the landmark 1905 Supreme Court decision in 'Kalem Co. v. Harper Bros.' which would ultimately set precedents for film adaptation rights.

Why This Film Matters

The 1907 Ben-Hur holds immense cultural significance as the first screen adaptation of one of America's most popular novels. It demonstrated that cinema could tackle serious, religious, and historical subjects, not just comedies and melodramas. The subsequent copyright lawsuit established crucial legal precedents regarding film rights to literary works, influencing the industry for decades. This film helped pave the way for future biblical epics and literary adaptations, showing that audiences would respond to serious subject matter on screen. It also represents an early example of the film industry's struggle with intellectual property rights, an issue that continues to this day. The film's existence proved that even in cinema's infancy, filmmakers had the ambition to tackle epic stories, setting the stage for the grand Hollywood productions that would follow.

Making Of

The production of Ben-Hur in 1907 was a significant undertaking for the Kalem Company. Director Sidney Olcott, a pioneering filmmaker who would later co-found Famous Players Film Company (Paramount's predecessor), faced numerous technical challenges. The galley scenes required the use of actual boats on water, which was difficult to film with the bulky equipment of the era. The production had to create makeshift ancient Jerusalem settings in New York and New Jersey, using whatever locations could pass for biblical times. Gene Gauntier, who played Esther and wrote the scenario, had to condense Wallace's massive novel into a screenplay that could be filmed in just 15 minutes. The cast worked in primitive conditions, with no dressing rooms or modern amenities. The film was shot quickly and efficiently, as was typical of the one-reel era, but with more attention to spectacle than most productions of its time.

Visual Style

The cinematography of the 1907 Ben-Hur was typical of the period but ambitious in scope. The film was shot in the standard one-reel format of the time, using stationary cameras with long takes. No close-ups or camera movements were employed, as these techniques had not yet been developed. The cinematographer had to work with natural lighting for the outdoor scenes, which limited shooting hours. The galley sequences presented particular challenges, requiring careful positioning of cameras to capture the action on water. The film used basic special effects for the time, including in-camera tricks and practical effects. While primitive by modern standards, the cinematography was considered impressive for 1907, especially in its attempt to convey the scale of the story through composition and staging.

Innovations

For its time, the 1907 Ben-Hur represented several technical achievements in early cinema. The successful filming of maritime sequences with actual boats on water was particularly noteworthy, as this required careful planning and execution with the bulky cameras of the era. The production managed to create convincing ancient settings using limited resources and locations in New York and New Jersey. The film demonstrated early attempts at crowd organization and staging, with multiple actors coordinated for key scenes. While not revolutionary in technical terms, the film pushed the boundaries of what was possible in a one-reel format, attempting to convey an epic story within severe time and technical constraints. The successful integration of location shooting with studio work showed the growing sophistication of American film production techniques.

Music

The 1907 Ben-Hur would have been accompanied by live musical performance during exhibition, as was standard for all films of the silent era. Theaters typically employed pianists or small ensembles to provide musical accompaniment. For a film with biblical and historical themes, the music would likely have included classical pieces, hymns, and popular songs of the era that fit the mood. Some theaters may have used cue sheets provided by the Kalem Company, suggesting appropriate music for different scenes. The galley scenes might have been accompanied by dramatic, martial music, while the religious elements would have featured more solemn, reverential pieces. Unfortunately, no specific musical scores or cue sheets for this particular film have survived.

Famous Quotes

No recorded dialogue exists from this silent film

Memorable Scenes

- The galley slave sequence, which was particularly ambitious for 1907 and required filming on actual water with boats

- The crucifixion scene, which represented one of the earliest attempts to depict this biblical event on film

- The opening scenes depicting Ben-Hur as a wealthy Jewish prince in Jerusalem

- The betrayal scene where Messala condemns Ben-Hur to slavery

Did You Know?

- This was the very first film adaptation of Lew Wallace's 1880 novel 'Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ'

- The film sparked a landmark copyright infringement lawsuit (Kalem Co. v. Harper Bros.) that established important precedents for film rights

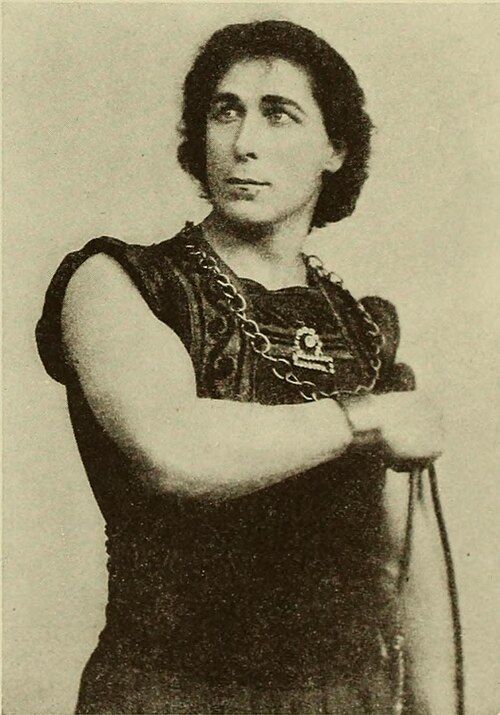

- Director Sidney Olcott also appears in the film in an uncredited role

- Gene Gauntier, who played Esther, also wrote the screenplay adaptation

- The entire film was shot on location in New York and New Jersey rather than on studio sets

- At 15 minutes, it was considered a long-form feature at a time when most films were only 1-3 minutes

- The galley sequence was one of the most complex maritime scenes attempted in American cinema up to that point

- The film's success led to numerous unauthorized adaptations of literary works in subsequent years

- Only a few production stills survive; the film itself is considered lost

- The copyright lawsuit resulted in the first Supreme Court decision to address film adaptation rights

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of the 1907 Ben-Hur was generally positive, with reviewers noting its ambitious scope and impressive spectacle for a one-reel film. The Moving Picture World praised its 'magnificent' production values and noted that it 'surpasses anything yet attempted in moving pictures.' Critics were particularly impressed by the galley scenes and the attempt to recreate biblical Jerusalem. However, some reviewers noted that the 15-minute format was insufficient to properly convey the novel's epic scope. Modern film historians view the 1907 Ben-Hur as a significant technical and artistic achievement for its time, though most acknowledge that it appears primitive by later standards. The film is now studied primarily for its historical importance and its role in establishing copyright precedents rather than its artistic merits.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1907 reportedly responded enthusiastically to Ben-Hur, which stood out from the typical short comedies and melodramas of the era. The film's biblical subject matter appealed to the predominantly family audiences of nickelodeons. Many viewers were impressed by the spectacle of the galley scenes and the attempt to recreate ancient settings. The film's success at the box office demonstrated that there was a market for more serious, literary adaptations, encouraging other studios to pursue similar projects. Contemporary accounts suggest that the film was particularly popular in areas with strong religious communities. However, some audience members may have been confused by the condensed narrative, as they were expected to be familiar with Wallace's novel to follow the story completely.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Lew Wallace's 1880 novel 'Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ'

- Stage adaptations of Ben-Hur (popular in the 1890s and early 1900s)

- Earlier biblical films like 'The Passion Play' (1898)

- Contemporary Italian historical epics

This Film Influenced

- Ben-Hur (1925)

- Ben-Hur (1959)

- Ben-Hur (2016)

- The King of Kings (1927)

- The Ten Commandments (1923 and 1956)

- Numerous biblical epics of the silent and sound eras

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The 1907 Ben-Hur is considered a lost film. No complete copies are known to survive, though a few production stills and promotional materials exist in archives. The film was likely lost due to the deterioration of nitrate film stock, which was common for films of this era. Some film historians hold out hope that a copy might exist in an unexamined archive or private collection, but as of now, the film is officially classified as lost. The loss of this historically significant film is particularly unfortunate given its role in establishing copyright precedents and its status as the first Ben-Hur adaptation.