Bluebeard

Plot

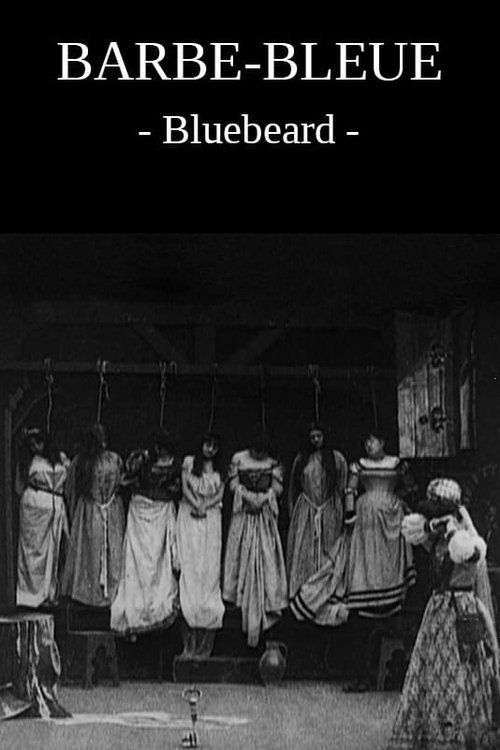

In this adaptation of the classic fairy tale, a wealthy nobleman known as Bluebeard seeks his eighth wife after his previous seven wives mysteriously disappeared. A young woman, despite her family's warnings, agrees to marry him. Bluebeard gives his new bride a key to all the rooms in his castle but strictly forbids her from entering one particular chamber. Overcome by curiosity, the young woman eventually opens the forbidden door and discovers the horrific truth - the bodies of Bluebeard's seven previous wives hanging from hooks. When Bluebeard returns and finds blood on the key, he flies into a rage and attempts to kill her. Just as he raises his sword, the woman's brothers burst in and save her, killing Bluebeard in the process.

Director

About the Production

Filmed in Méliès's glass studio in Montreuil, the film used elaborate painted backdrops and stage machinery to create the castle interiors. The production employed Méliès's signature substitution splices and multiple exposure techniques for magical effects. The hanging bodies scene was achieved using dummies and wires, a technically challenging effect for 1901. The film was shot on 35mm film with a hand-cranked camera, typical of the era.

Historical Background

Made in 1901, 'Bluebeard' emerged during the pioneering years of cinema when filmmakers were transitioning from simple actualities to narrative storytelling. The film was created just six years after the Lumière brothers' first public screening in 1895. At this time, Georges Méliès was establishing himself as cinema's first visionary director, discovering the possibilities of film as a medium for fantasy and spectacle. The early 1900s saw the rise of permanent film theaters and the beginning of film as a commercial industry. Méliès's Star Film Company was competing internationally with other emerging studios. This period also witnessed the development of film grammar, including editing techniques and narrative structures that would become standard in cinema.

Why This Film Matters

'Bluebeard' represents a crucial milestone in the development of narrative cinema, demonstrating how filmmakers could adapt literary works to the new medium. The film helped establish the horror genre in cinema, being one of the earliest films to deal with macabre themes and create genuine suspense. Méliès's adaptation showed how visual storytelling could convey complex narratives without intertitles or dialogue. The film's success contributed to the popularity of fairy tale adaptations in early cinema, influencing countless subsequent filmmakers. It also demonstrated cinema's potential to handle dark, adult themes, expanding the medium beyond simple entertainment. The technical innovations in special effects pioneered in this film would influence generations of filmmakers and establish visual effects as a crucial component of cinematic storytelling.

Making Of

Georges Méliès, a former magician and theater owner, applied his stagecraft expertise to create this cinematic adaptation of the famous fairy tale. The film was shot in his glass-walled studio in Montreuil, which allowed natural lighting while protecting against weather. Méliès employed his pioneering special effects techniques, including substitution splices for the appearance and disappearance of characters, and multiple exposures for ghostly effects. The most challenging scene was the revelation of the hanging bodies, which required careful rigging of dummies and precise camera work. The production involved painted backdrops created by Méliès's team of artists, who worked from theatrical set designs. The actors, including Méliès's frequent collaborators Jehanne d'Alcy and Bleuette Bernon, performed in the theatrical style typical of early cinema, with exaggerated gestures to convey emotion without dialogue.

Visual Style

The cinematography, typical of Méliès's work, employed a static camera positioned to capture the theatrical action like a proscenium arch. The film was shot in black and white with hand-tinted color versions available for premium showings. The camera work was straightforward but effective, using the fixed perspective to emphasize the staged nature of the performance. The lighting was natural, coming through the glass walls of Méliès's studio, creating dramatic shadows that enhanced the horror elements. The cinematography prioritized clarity of the special effects over artistic camera movement, as the focus was on Méliès's innovative visual tricks rather than photographic experimentation.

Innovations

The film showcased several of Méliès's pioneering technical innovations, including substitution splices for magical appearances and disappearances, multiple exposure techniques for creating ghostly effects, and elaborate set construction that moved beyond simple painted backdrops. The hanging bodies scene demonstrated advanced use of wires and rigging for special effects. The film also featured sophisticated editing for its time, with cuts used to create narrative continuity and dramatic tension. Méliès's use of stage machinery adapted for film was particularly innovative, allowing for dynamic scene changes and effects that would influence future filmmakers. The color tinting process, used in some versions of the film, represented an early attempt to add visual richness to monochrome cinema.

Music

As a silent film, 'Bluebeard' would have been accompanied by live music during its original screenings. The typical accompaniment would have been a pianist or small orchestra playing appropriate music to match the mood of each scene. For the dramatic moments, tense and suspenseful music would be played, while lighter themes would accompany the romantic scenes. Some theaters might have used compiled classical pieces, while others might have had specially composed scores. The exact musical accompaniment would have varied by theater and performer, as there was no standardized score for the film.

Famous Quotes

'You may enter any room in the castle, but this one door must never be opened.' (Bluebeard's warning to his wife)

'Curiosity killed the cat, but satisfaction brought it back.' (Implied theme throughout the film)

Memorable Scenes

- The shocking revelation scene where the young wife opens the forbidden door to discover the seven hanging bodies of Bluebeard's previous wives, achieved through elaborate special effects that were terrifying for 1901 audiences

Did You Know?

- This was one of Méliès's longer films at the time, running approximately 2.5 minutes when most films were under a minute

- The film is based on Charles Perrault's 1697 fairy tale 'La Barbe bleue'

- Méliès himself played Bluebeard, continuing his practice of starring in his own films

- The hanging bodies scene was considered shocking for its time and was sometimes censored in certain markets

- The film was released by Méliès's Star Film Company and cataloged as No. 328-329 in their listings

- The elaborate castle set was one of Méliès's most expensive productions of 1901

- The film features one of cinema's earliest depictions of a serial killer character

- Méliès used the same basic set design techniques he would later employ in 'A Trip to the Moon' (1902)

- The brothers' dramatic entrance was achieved using stage machinery from Méliès's theater background

- This film was part of Méliès's series of fairy tale adaptations that helped establish narrative cinema

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's ambitious storytelling and technical achievements, particularly noting the impressive special effects and elaborate production design. The film was well-received by trade publications of the era, which highlighted Méliès's ability to bring theatrical spectacle to the screen. Modern critics and film historians recognize 'Bluebeard' as an important work in early cinema, praising its role in developing narrative film techniques and the horror genre. The film is often cited in scholarly works about Méliès's contributions to cinema and the development of visual effects. Contemporary analysis focuses on the film's sophisticated use of editing and its influence on subsequent fairy tale adaptations.

What Audiences Thought

The film was popular with audiences of its time, who were fascinated by its shocking content and spectacular effects. Reports from the period indicate that the revelation scene of the hanging bodies often elicited strong reactions from viewers, ranging from gasps to occasional fainting spells. The film's success led to numerous showings across Europe and America, where it was distributed by the Star Film Company. Modern audiences viewing the film in retrospectives and film festivals appreciate it as a historical artifact and an example of early cinematic artistry. The film continues to be shown in silent film festivals and Méliès retrospectives, where it generates interest from cinema enthusiasts and scholars.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Charles Perrault's fairy tale 'Barbe bleue' (1697)

- Gothic literature tradition

- Stage melodramas of the 19th century

- Theatrical special effects traditions

This Film Influenced

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

- Nosferatu (1922)

- The Phantom of the Opera (1925)

- Later horror film adaptations of fairy tales

- Countless films featuring the 'forbidden room' trope

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in multiple copies, including hand-tinted color versions, and has been preserved by film archives including the Cinémathèque Française. The film has been restored and digitized as part of various Méliès collections, ensuring its survival for future generations. Some versions show minor deterioration but are largely viewable. The film is included in the complete Méliès collection preserved by various international film archives.