Bosko, the Talk-Ink Kid

Plot

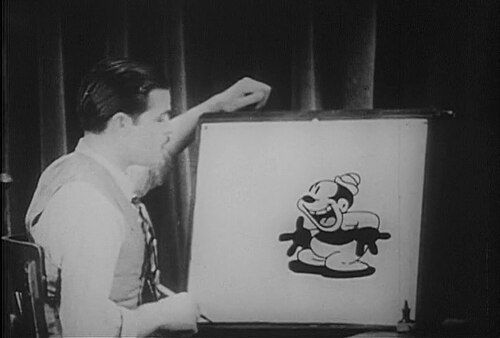

In this pioneering animated short, Bosko, a cheerful and energetic character with a simple circular design, emerges from an inkwell and comes to life through synchronized sound. The film showcases Bosko's musical talents as he sings, dances, and plays various instruments while interacting with simple animated objects. The character demonstrates his ability to speak clearly and perform synchronized movements to music, highlighting the technical possibilities of sound animation. The short concludes with Bosko returning to the inkwell, having successfully demonstrated his potential as an animated star. This pilot film was designed to showcase the character's personality and capabilities to potential studio executives.

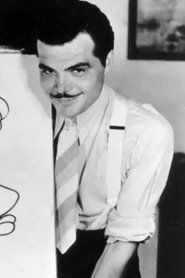

Director

About the Production

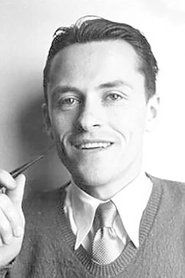

Created as a demonstration pilot to secure a distribution contract. Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising produced this independently after leaving Disney Studios. The animation was done on a shoestring budget with minimal resources. Carman Maxwell provided the voice for Bosko, making him one of the first animated characters with a distinctive speaking voice. The synchronization of sound and animation was achieved using the Photophone system, which was cutting-edge technology for the time.

Historical Background

1929 was a pivotal year in animation history, marking the full transition from silent to sound cartoons following the success of Disney's 'Steamboat Willie' in 1928. The film industry was rapidly embracing sound technology, and animation studios were racing to develop characters and techniques that could take advantage of synchronized audio. The Great Depression was beginning, making it a challenging time to secure financing for new ventures. Harman and Ising's creation of Bosko represented the entrepreneurial spirit of animators seeking independence from the major studios. This period also saw the emergence of racial caricatures in popular entertainment, reflecting the social attitudes of the time. The success of this pilot helped establish Warner Bros. as a major player in animation, creating competition that would drive innovation throughout the 1930s.

Why This Film Matters

Bosko represents a crucial milestone in animation history as one of the first synchronized sound characters and the star of Warner Bros.' inaugural cartoon series. While the character's origins in racial stereotypes are problematic by modern standards, Bosko paved the way for the development of more sophisticated animated characters. The success of this pilot led to the creation of the Looney Tunes brand, which would eventually produce iconic characters like Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and Porky Pig. Bosko's design philosophy of simple, expressive shapes influenced character design for decades. The film also demonstrated the commercial viability of sound animation, encouraging investment in the medium. The character's eventual evolution and retirement reflect changing social attitudes and the animation industry's growing awareness of racial sensitivity.

Making Of

Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising created this pilot after their departure from Walt Disney's studio, where they had worked on early Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoons. They were determined to create their own character and studio, investing their personal savings into this demonstration. The animation was done in a small makeshift studio with limited equipment. Carman Maxwell, one of their animators, had a unique voice that they decided to use for the character, recording his dialogue and songs directly onto the film's soundtrack. The team worked tirelessly to perfect the synchronization, which was technically challenging in 1929. When they presented the film to Warner Bros. executive Leon Schlesinger, he was immediately impressed and offered them a contract to produce a series of cartoons, which would become the foundation of what would later evolve into the Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies series.

Visual Style

The animation employed early cel animation techniques with black and white photography. The visual style was simple yet effective, featuring clean lines and minimal backgrounds to focus attention on the character. The inkwell sequence used innovative camera work to create the illusion of a character emerging from liquid. The animation was synchronized to sound using the Photophone system, requiring precise timing of each frame. The character design used basic geometric shapes - primarily circles and ovals - making him relatively easy to animate consistently. The visual humor relied heavily on exaggerated movements and expressions, techniques that would become staples of Warner Bros. animation.

Innovations

This short represented a significant technical achievement in early sound animation, particularly in the synchronization of voice with character movement. The successful implementation of synchronized speech in animation was still relatively new in 1929, with Disney's Mickey Mouse being one of the few precedents. The film demonstrated that complex character animation could be effectively combined with clear dialogue and musical performance. The inkwell effect, where Bosko appears to emerge from liquid, was an innovative special effect for the time. The production also proved that high-quality sound animation could be produced independently of the major studios, encouraging the growth of the animation industry.

Music

The soundtrack was revolutionary for its time, featuring synchronized dialogue, music, and sound effects. Carman Maxwell provided both the speaking voice and singing for Bosko, performing several musical numbers that demonstrated the character's talents. The music was simple, jaunty piano accompaniment typical of early sound cartoons. Sound effects were created using basic studio techniques but effectively synchronized with the animation. The entire soundtrack was recorded directly onto film using the Photophone sound-on-film process, which was competing with other sound systems of the era. The clarity of the voice recording was particularly impressive for 1929, helping to establish Bosko as a distinct personality.

Famous Quotes

"Well, hello folks!"

"I'm Bosko, the talk-ink kid!"

Musical performance: "Minnie the Moocher" style scat singing

"Watch me dance and sing!"

Memorable Scenes

- Bosko emerging from the inkwell with a splash effect

- The character's synchronized dancing and singing routine

- The final scene where Bosko returns to the inkwell after his performance

Did You Know?

- Bosko was originally conceived as a parody of a blackface performer, reflecting the racial stereotypes of the era

- Hugh Harman based Bosko's character design on his childhood memories of a friend who was African American

- The film was created using a synchronized sound system before Disney's similar technology became widely available

- Carman Maxwell, who voiced Bosko, was an animator who worked with Harman and Ising and had a distinctive high-pitched voice

- This pilot was shown to multiple studios including Universal, Paramount, and eventually Warner Bros.

- The success of this pilot led to the creation of the Looney Tunes series at Warner Bros.

- Bosko was the first character created specifically for Warner Bros.' animation division

- The inkwell concept was inspired by early animation techniques where characters would literally emerge from drawings

- Only one print of this film was known to exist for decades, making it extremely rare

- The character's name 'Bosko' was reportedly derived from 'bosko,' a term used in some African American communities

What Critics Said

Since 'Bosko, the Talk-Ink Kid' was never publicly released, critical reviews from contemporary sources do not exist. However, studio executives who viewed the pilot reportedly responded positively, particularly Leon Schlesinger of Warner Bros., who immediately saw commercial potential in the character and the synchronized sound technique. Modern animation historians and critics regard the film as historically significant, praising its technical achievements while acknowledging its dated racial elements. Film scholars often cite it as an important example of early sound animation and a key document in understanding the development of American animation studios during the transition to sound.

What Audiences Thought

As this was a pilot film never shown to general audiences, there is no record of public reception. The intended audience was studio executives and potential investors, whose positive response led to the character being picked up by Warner Bros. Later, when Bosko cartoons were released to the public, audiences generally responded favorably to the character's musical abilities and energetic personality, though by today's standards the racial caricature elements would be considered offensive.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Steamboat Willie (1928)

- Felix the Cat cartoons

- Early Disney sound shorts

- Vaudeville performance traditions

- Minstrel show conventions

This Film Influenced

- Bosko the Doughboy (1931)

- Sinkin' in the Bathtub (1930)

- Congo Jazz (1930)

- Hold Anything (1930)

- The early Looney Tunes series

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film exists in archives but is extremely rare. A copy is preserved at the UCLA Film and Television Archive. The original negative status is unknown, but surviving prints have been used for documentary purposes. The film has been included in some Warner Bros. animation retrospective collections.