Close-Up

"The story of a man who impersonated a director and the director who impersonated a man."

Plot

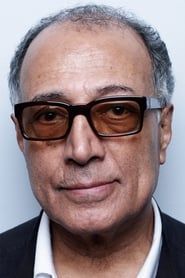

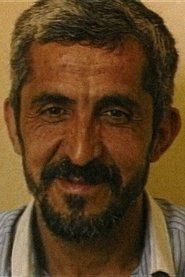

Abbas Kiarostami's groundbreaking film documents and reenacts the true story of Hossain Sabzian, an unemployed film enthusiast who impersonates renowned Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf to gain entry into the wealthy Ahankhah family's home. Sabzian convinces the family he wants to use their house as a filming location, leading them to invest money and time in what they believe is a legitimate film project. When the deception is discovered, Sabzian is arrested and charged with fraud, but rather than simply documenting the trial, Kiarostami intervenes to have the actual participants recreate events from their case. The film seamlessly blends documentary footage of the real trial with reenacted scenes featuring the actual people involved, including Sabzian himself, the Ahankhah family, and even the real Mohsen Makhmalbaf. Through this innovative approach, Kiarostami explores themes of identity, artistic creation, the nature of truth in cinema, and the human desire for recognition and purpose.

About the Production

Kiarostami learned about Sabzian's case from a magazine article and immediately recognized its cinematic potential. The director faced the unique challenge of convincing both the accused and the victims to participate in recreating their traumatic experience. The production was characterized by its improvisational approach, with Kiarostami often letting scenes unfold naturally rather than strictly scripting them. The film was shot on 16mm and later blown up to 35mm for international distribution. The courtroom scenes were filmed during the actual trial, with Kiarostami obtaining special permission from the judicial authorities. The blending of documentary and fiction was so seamless that many viewers initially believed they were watching a pure documentary.

Historical Background

Close-Up emerged during a fascinating period in Iranian cinema, following the 1979 Islamic Revolution when the film industry underwent dramatic transformation. The post-revolution government established strict censorship codes but also provided state funding for films that aligned with Islamic values, inadvertently creating a new wave of minimalist, poetic cinema that worked within and around these constraints. The late 1980s saw the rise of the Iranian New Wave, with directors like Kiarostami developing a distinctive style characterized by long takes, non-professional actors, and philosophical themes. Close-Up was created during this renaissance, reflecting both the limitations and creative opportunities of its time. The film's focus on class differences and the desire for artistic recognition resonated with a society undergoing rapid modernization while grappling with traditional values. Its production coincided with Iran's post-war reconstruction period after the Iran-Iraq War, a time when many Iranians were questioning their identity and place in the world.

Why This Film Matters

Close-Up is widely regarded as one of the most important films in world cinema history, fundamentally challenging the boundaries between documentary and fiction. The film's innovative approach to storytelling influenced countless filmmakers worldwide, including directors like Werner Herzog, Spike Jonze, and the Dardenne brothers. It established Abbas Kiarostami as a major figure in international cinema and helped put Iranian cinema on the global map. The film's exploration of the relationship between reality and representation has made it a staple in film studies programs worldwide. Its success at international festivals demonstrated that films from Iran could compete on the global stage without compromising their cultural specificity. The movie also sparked important discussions about ethics in documentary filmmaking and the responsibility of filmmakers toward their subjects. In Iran, the film became a cultural touchstone, referenced in subsequent Iranian works and studied as an example of how to work creatively within censorship constraints. Its selection for preservation in the U.S. National Film Registry in 2022 cemented its status as a culturally, historically, and aesthetically significant work.

Making Of

The making of 'Close-Up' was as unconventional as the film itself. Kiarostami first read about Sabzian's case in a magazine article and was immediately fascinated by the philosophical questions it raised about identity and art. He spent months convincing all parties involved to participate in the project, emphasizing that this was an opportunity to explore deeper truths beyond the simple facts of the case. The production team faced numerous challenges, including obtaining permission to film in the actual courtroom and convincing the Ahankhah family to relive their humiliation on camera. Kiarostami's approach was to create a space where documentary and fiction could merge seamlessly, often letting scenes play out without strict direction. The famous final scene where Sabzian meets the real Makhmalbaf was completely unscripted and captured in one take. The film's innovative structure influenced a generation of filmmakers and established Kiarostami as a master of blending reality and fiction.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Close-Up, handled by Mahmoud Kalari, is notable for its documentary-style realism and intimate framing. The film employs a mix of handheld camera work for the documentary sequences and more composed shots for the reenacted scenes, creating a subtle visual distinction between reality and recreation. Kalari uses natural lighting throughout, enhancing the film's authenticity and grounding it in the everyday reality of Tehran. The camera often maintains a respectful distance from its subjects, particularly in emotional moments, allowing them space without being intrusive. The courtroom scenes are shot from multiple angles, giving viewers a comprehensive view of the proceedings while maintaining the feeling of observation rather than intrusion. The famous final scene with Sabzian and Makhmalbaf is shot with a long lens, creating a sense of both intimacy and distance that perfectly encapsulates the film's themes. The color palette is naturalistic, reflecting the urban environment of Tehran without romanticization.

Innovations

Close-Up's most significant technical achievement is its seamless integration of documentary footage and staged sequences, creating a hybrid form that feels both authentic and cinematic. The film pioneered techniques that would later be adopted by reality television and mockumentary filmmakers, though with far greater artistic sophistication. The production team developed innovative methods for capturing authentic reactions while maintaining cinematic quality, including the use of hidden cameras in certain scenes. The film's editing, supervised by Abbas Kiarostami himself, creates a rhythmic flow between past and present, reality and recreation, without confusing the viewer. The technical team also solved the challenge of filming in an actual courtroom by using multiple cameras and obtaining special permissions. The film's successful transfer from 16mm to 35mm for international distribution while maintaining its visual quality was another technical accomplishment. The movie's influence on documentary filmmaking techniques cannot be overstated, with its approach to reenactment becoming a reference point for countless subsequent works.

Music

Close-Up features minimal use of music, with most of the soundtrack consisting of ambient sounds from Tehran and the natural dialogue of its participants. The few musical moments are carefully chosen and often diegetic, such as the sound of a radio or street musicians. The film's most notable use of music comes during the final scene, where a gentle piano melody underscores the meeting between Sabzian and Makhmalbaf, providing emotional resonance without being manipulative. The sound design emphasizes the authenticity of the documentary elements, with street noises, courtroom echoes, and the natural acoustics of the Ahankhah family home all contributing to the film's immersive quality. The lack of a traditional score reinforces the film's documentary approach and prevents emotional manipulation, allowing viewers to form their own responses to the events depicted. The sparse use of music makes the moments when it does appear particularly impactful.

Famous Quotes

I wanted to be someone. I wanted to be important. I wanted to be respected.

Hossain Sabzian

Cinema is the most beautiful fraud in the world.

Often attributed to the film's themes

I'm not a fraud. I'm an artist.

Sabzian during his trial

We all want to be someone we're not.

A central theme expressed through dialogue

The camera is not just recording, it's creating.

Kiarostami's implicit statement

Truth is stranger than fiction, but not as strange as the truth about fiction.

Summarizing the film's approach

I wanted to make people happy through cinema.

Sabzian explaining his motivations

Art is the lie that enables us to realize the truth.

Reflecting Picasso's words, relevant to the film

Every film is a documentary of its own making.

A meta-commentary within the film

I didn't deceive them. I gave them a dream.

Sabzian's defense of his actions

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Kiarostami explains how he learned about Sabzian's case, immediately establishing the film's meta-narrative approach

- The tense confrontation scene where the Ahankhah family discovers Sabzian's deception, filmed with raw emotional intensity

- The courtroom scenes where real footage and reenactments merge seamlessly, creating a disorienting but powerful effect

- The climactic meeting between Sabzian and the real Mohsen Makhmalbaf, captured in a single unscripted take that embodies the film's themes

- The scene where Sabzian rides on Makhmalbaf's motorcycle through Tehran, a moment of redemption and reconciliation

- The final shot of the film, where Sabzian looks directly into the camera, breaking the fourth wall and challenging the audience's role as observers

Did You Know?

- The film was shot in just 11 days, an incredibly short period even for a low-budget production

- Hossain Sabzian was serving his sentence when Kiarostami approached him about participating in the film

- The real Mohsen Makhmalbaf makes a cameo appearance in the film, riding on a motorcycle with Sabzian

- Kiarostami paid the Ahankhah family's legal fees as compensation for their participation

- The film was initially banned in Iran but later approved after Kiarostami made some cuts

- Many of the scenes, particularly the emotional ones, were improvised by the non-professional actors

- The taxi driver who first discovers Sabzian's deception plays himself in the film

- Kiarostami used hidden cameras for some scenes to capture authentic reactions

- The film's title in Persian is 'Nema-ye Nazdik', which literally translates to 'Close View'

- The film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry in 2022

What Critics Said

Close-Up received universal acclaim from critics upon its release and continues to be celebrated as a masterpiece of world cinema. Roger Ebert gave it four stars, calling it 'a film that not only entertains but also expands our consciousness about the nature of cinema itself.' The New York Times' Vincent Canby praised its 'extraordinary formal and emotional complexity.' French critic Jean-Michel Frodon described it as 'one of the most profound films ever made about the cinema.' The film's reputation has only grown over time, with many contemporary critics placing it among the greatest films ever made. Sight & Sound's 2022 critics' poll ranked it 28th on its list of the greatest films of all time. The film is particularly praised for its innovative structure, philosophical depth, and humane treatment of its subjects. Critics have noted how Kiarostami's approach transcends simple documentary to create something entirely new in cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception in Iran was mixed, with some viewers confused by the film's blurring of reality and fiction. However, among cinephiles and educated audiences, the film quickly gained recognition as a groundbreaking work. International audiences, particularly at film festivals, responded enthusiastically, with the film receiving standing ovations at Cannes. Over time, the film has developed a cult following among cinema enthusiasts worldwide. On modern review aggregator sites, Close-Up maintains exceptionally high ratings, with Letterboxd users rating it 4.4/5 and IMDb users giving it 8.0/10. The film's reputation has grown through home video releases and streaming availability, introducing it to new generations of viewers. Many audience members report that the film changes their understanding of what cinema can be, with its meta-narrative approach and philosophical depth provoking long discussions after viewing.

Awards & Recognition

- Cannes Film Festival - FIPRESCI Prize (1990)

- Cannes Film Festival - Un Certain Regard Prize (1990)

- Fajr Film Festival - Best Director (1991)

- Tokyo International Film Festival - Special Jury Prize (1990)

- Sundance Film Festival - World Cinema Jury Prize (1991)

- National Society of Film Critics - Best Film (1992)

- New York Film Critics Circle - Best Foreign Film (1991)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Italian Neorealism (particularly De Sica's 'Bicycle Thieves')

- Jean-Luc Godard's self-reflexive cinema

- Documentary traditions of Frederick Wiseman

- Persian literary traditions of storytelling

- The works of Satyajit Ray

- French New Wave cinema

- Direct Cinema movement

- Theater of the Absurd

This Film Influenced

- Man Bites Dog (1992)

- The Blair Witch Project (1999)

- American Movie (1999)

- F for Fake (1973) - though predating, it shares similar themes

- Stories We Tell (2012)

- The Act of Killing (2012)

- Exit Through the Gift Shop (2010)

- I'm Still Here (2010)

- The Arbor (2010)

- The Missing Person (2009)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Close-Up has been well-preserved and restored multiple times. The original 16mm negatives are maintained in the Iranian Film Archive. In 2015, the Criterion Collection released a digitally restored version in conjunction with Janus Films, supervised by cinematographer Mahmoud Kalari. The film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry in 2022, recognizing its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance. The British Film Institute also maintains a preserved copy in its archive. Multiple restoration projects have ensured the film remains accessible in high quality for contemporary audiences, with 4K restorations completed for both theatrical and home video releases.