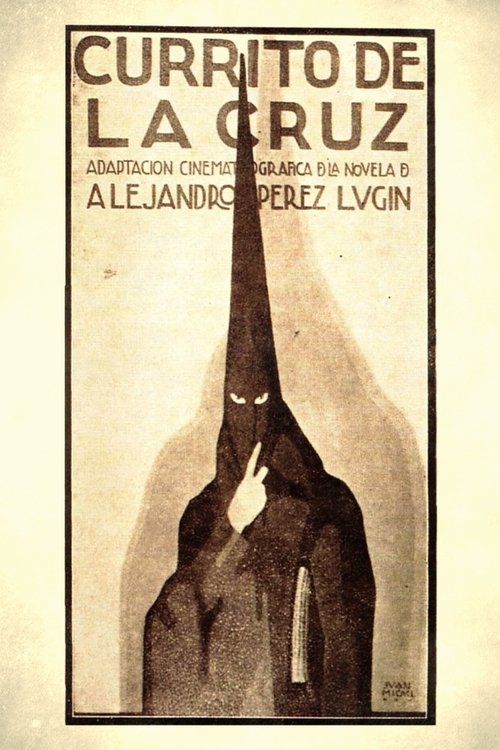

Currito de la Cruz

"La historia de un humilde muchacho que conquistó la fama en el ruedo"

Plot

Currito de la Cruz follows the journey of a young man raised in a Seville hospice who dreams of becoming a successful bullfighter. Despite his humble origins and lack of formal training, Currito possesses natural talent and determination that catch the attention of experienced matadors. He falls in love with María, the daughter of a retired bullfighter who initially disapproves of their relationship due to Currito's low social status. Through perseverance and with the help of mentors, Currito eventually gets his chance in the bullring, where he must prove himself not only as a skilled matador but also as a worthy man in the eyes of María's father. The film culminates in a dramatic bullfighting sequence where Currito faces both physical danger and the ultimate test of his character, ultimately achieving his dream and winning social acceptance.

About the Production

The film was adapted from Alejandro Pérez Lugín's own novel of the same name, published in 1921. Lugín, who was both a novelist and filmmaker, took great care to ensure authenticity in the bullfighting sequences, hiring real matadors as consultants and extras. The production faced significant challenges in capturing the dangerous bullfighting scenes safely, requiring innovative camera techniques and careful choreography. The film was one of the most ambitious Spanish productions of its time, with extensive location shooting in authentic Andalusian settings.

Historical Background

'Currito de la Cruz' was produced during a pivotal period in Spanish history and cinema. The mid-1920s saw Spain under the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera (1923-1930), a time of relative political stability but also growing social tensions. The film emerged during what is now considered the golden age of Spanish silent cinema (1923-1929), when domestic production flourished and Spanish filmmakers began developing a distinct national cinematic identity. The bullfighting theme was particularly significant as it represented traditional Spanish culture at a time when Spain was grappling with modernization and its place in contemporary Europe. The film's focus on social mobility through individual talent reflected broader societal debates about class and opportunity in Spanish society. Additionally, the film was made just before the transition to sound cinema, which would dramatically transform the film industry worldwide. Its success demonstrated that Spanish cinema could compete artistically and commercially with foreign productions, particularly in telling distinctly Spanish stories.

Why This Film Matters

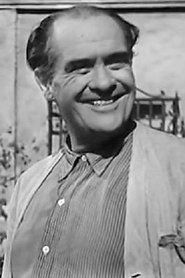

'Currito de la Cruz' holds immense cultural significance as one of the foundational texts of Spanish cinema. The film helped establish the bullfighting movie as a quintessentially Spanish genre, one that would be revisited repeatedly throughout Spanish film history. It captured and codified many of the romantic notions about Spanish identity, honor, and tradition that would influence both domestic and international perceptions of Spain for decades. The film's portrayal of social mobility through personal excellence resonated deeply with Spanish audiences of the 1920s, reflecting aspirations for change within a traditionally hierarchical society. Its success demonstrated that Spanish audiences hungered for stories that reflected their own culture and values, rather than imported Hollywood productions. The film also helped launch the career of Jesús Tordesillas, who would become one of Spain's most beloved actors. Perhaps most importantly, 'Currito de la Cruz' established a template for how Spanish cinema could engage with national traditions while addressing universal themes of love, ambition, and social acceptance.

Making Of

The production of 'Currito de la Cruz' was a significant undertaking for 1926 Spanish cinema. Director Alejandro Pérez Lugín, adapting his own bestselling novel, insisted on absolute authenticity in depicting the bullfighting world. He spent months researching the technical aspects of bullfighting and consulted with active matadors to ensure accuracy. The filming of the bullfighting sequences presented enormous challenges, as the crew had to work with real bulls while ensuring the safety of cast and crew. Special camera rigs and protective barriers were designed to capture close-up shots of the action. Jesús Tordesillas underwent extensive training to perfect his bullfighting technique, though his previous experience as a novillero (novice bullfighter) proved invaluable. The production also faced difficulties in securing permission to film in the historic Plaza de toros de Sevilla, which had rarely been used for film productions. The film's success led to increased interest in Spanish cinema internationally and helped establish a template for future Spanish films focusing on national traditions and culture.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Currito de la Cruz' was groundbreaking for its time, particularly in the filming of the bullfighting sequences. The cinematographer employed innovative techniques including multiple camera setups to capture the action from various angles, creating a dynamic sense of movement and danger. The use of location shooting in Seville's authentic settings provided a visual richness that contrasted with the more common studio-bound productions of the era. The film made effective use of natural light, particularly in outdoor scenes, creating a distinctive Andalusian atmosphere. The bullfighting sequences utilized specially designed camera rigs that could get closer to the action while maintaining safety, allowing for shots that had never been achieved before in Spanish cinema. The visual style combined documentary-like realism in the bullfighting scenes with more romantic, pictorial compositions for the dramatic sequences, creating a visual language that balanced authenticity with narrative requirements. The film's visual approach influenced subsequent Spanish films dealing with traditional subjects and helped establish a visual vocabulary for depicting Spanish culture on screen.

Innovations

'Currito de la Cruz' featured several technical innovations that were significant for Spanish cinema of the 1920s. The most notable achievement was the sophisticated filming of the bullfighting sequences, which required custom-built camera protection and innovative placement to capture the dangerous action safely. The production team developed a system of mirrors and angled shots that allowed them to film closer to the bull than had previously been possible. The film also employed advanced editing techniques for its time, using cross-cutting between the bullfight and audience reactions to build tension. The location shooting in Seville presented technical challenges that the crew overcame using portable power generators and mobile camera equipment, demonstrating growing technical sophistication in Spanish film production. The film's preservation and restoration in later decades also pioneered techniques for recovering and enhancing deteriorating nitrate film stock, making it an important case study in film preservation. These technical achievements not only served the narrative needs of 'Currito de la Cruz' but also advanced the technical capabilities of the Spanish film industry as a whole.

Music

As a silent film, 'Currito de la Cruz' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical presentation would have featured a pianist or small orchestra performing a combination of classical pieces, popular Spanish songs, and specially composed cues synchronized with the on-screen action. The musical selections would have included traditional Spanish pieces such as pasodobles during the bullfighting sequences and romantic melodies for the dramatic scenes. While no original score was composed specifically for the film, contemporary accounts suggest that theaters often used pieces from composers like Isaac Albéniz and Enrique Granados to enhance the Spanish atmosphere. In modern screenings and restorations, the film has been accompanied by newly composed scores that attempt to recreate the musical experience of 1920s Spanish cinema. These contemporary scores typically incorporate traditional Spanish instruments and musical forms to maintain the film's cultural authenticity while meeting modern expectations for film music.

Famous Quotes

"En el ruedo de la vida, todos tenemos nuestro toro que enfrentar" - Currito

"No nací con silver, pero llevo el corazón de un torero" - Currito

"El valor no se mide por la cuna, sino por los hechos" - Retired matador

"En cada corrida, el verdadero enemigo es el miedo" - Mentor to Currito

"El amor, como el toreo, exige entrega y valentía" - María

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic bullfighting sequence where Currito faces his first bull as a professional matador, combining technical excellence with emotional intensity

- The scene where Currito first meets María at the Seville hospice, establishing their instant connection despite social barriers

- The training montage where Currito practices bullfighting moves in empty fields at dawn, showing his dedication

- The confrontation scene between Currito and El Chirlo, his rival, which establishes the competitive tension

- The emotional finale where Currito receives his alternative as a matador, symbolizing his acceptance into Spanish society

Did You Know?

- This was the first film adaptation of Alejandro Pérez Lugín's popular novel, which would be remade multiple times, including a 1936 sound version and a 1949 version.

- Director Alejandro Pérez Lugín was a renowned Spanish novelist before turning to filmmaking, bringing literary sensibility to his cinematic work.

- The bullfighting sequences were considered groundbreaking for their time, using multiple cameras and innovative angles to capture the action safely.

- Jesús Tordesillas, who played Currito, was actually an experienced bullfighter in his youth before turning to acting, bringing authenticity to the role.

- The film's success helped establish the 'torero' (bullfighter) film as a significant genre in Spanish cinema.

- Real matadors from the era appeared as extras and consultants in the bullfighting scenes.

- The film was shot during the golden age of Spanish silent cinema, just before the transition to sound began.

- Preservation efforts in the 1990s restored several minutes of footage that had been considered lost.

- The original novel was based on real people Lugín had encountered in Seville's bullfighting circles.

- The film's premiere in Madrid was attended by prominent members of Spanish aristocracy and bullfighting aficionados.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'Currito de la Cruz' for its technical excellence, particularly the innovative filming of the bullfighting sequences. The Madrid newspaper 'El Sol' hailed it as 'a triumph of Spanish cinema' that proved domestic productions could match the quality of foreign films. Critics specifically noted Alejandro Pérez Lugín's skill in translating his literary sensibility to the visual medium, and Jesús Tordesillas' performance was widely acclaimed for its authenticity and emotional depth. The film's visual style, particularly its use of location shooting in Seville, was praised for bringing Andalusian culture to life on screen. Modern film historians have reassessed the film as a milestone in Spanish cinema, noting its role in establishing a national cinematic identity. Spanish film historian Carlos F. Heredero has called it 'perhaps the most important Spanish silent film of the 1920s' for its technical achievements and cultural impact. The film is now studied in Spanish film courses as an exemplar of early Spanish narrative cinema and its engagement with national themes.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1926 Spain embraced 'Currito de la Cruz' with enormous enthusiasm, making it one of the most successful domestic productions of the year. The film resonated particularly strongly with working-class audiences who identified with Currito's struggle for social advancement. Bullfighting aficionados praised the authenticity of the bullfighting sequences, while general audiences were drawn to the romantic storyline and the portrayal of traditional Spanish culture. The film ran for extended engagements in Madrid and Barcelona, unusual for Spanish productions of the era which typically had shorter theatrical runs. Audience reactions were especially emotional during the bullfighting scenes, with contemporary accounts describing viewers gasping and cheering in theaters as if they were watching a real bullfight. The film's success led to increased demand for Spanish productions and helped establish a domestic market for films that reflected Spanish culture and values. In the decades since its release, the film has maintained its reputation among Spanish film enthusiasts as a classic of early Spanish cinema, with periodic revivals at film festivals and retrospectives continuing to draw appreciative audiences.

Awards & Recognition

- Medalla al Mérito Cinematográfico (Spanish Film Merit Medal) - 1927

- Best Spanish Film at the International Film Exhibition of San Sebastián - 1926

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The novels of Pérez Lugín

- Italian neorealist cinema's emphasis on social issues

- American silent film storytelling techniques

- Spanish literary tradition of the picaresque novel

- Traditional Spanish corrido de toros literature

This Film Influenced

- Blood and Sand (1941)

- The Young One (1960)

- Currito de la Cruz (1936 remake)

- Currito de la Cruz (1949 remake)

- The Spirit of the Beehive (1973)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Partially preserved - While some footage was lost over the decades, restoration efforts in the 1990s recovered and restored approximately 75% of the original film. The Filmoteca Española holds the most complete version, though some scenes remain incomplete. The restored version includes newly created intertitles to replace lost original text. The film exists on 35mm film stock and has been digitized for preservation purposes. Some original nitrate footage was too deteriorated to save, but what remains provides a substantial representation of the original work.