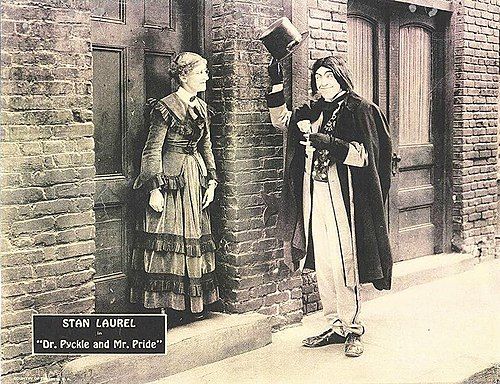

Dr. Pyckle and Mr. Pride

"A Jekyll and Hyde of Laughs!"

Plot

Dr. Pyckle and Mr. Pride is a silent comedy parody that follows the story of a mild-mannered scientist named Dr. Pyckle who creates a potion that transforms him into his arrogant and mischievous alter ego, Mr. Pride. Unlike the dark and terrifying transformation in Robert Louis Stevenson's original tale, this version presents the change through slapstick comedy and visual gags. The film follows Dr. Pyckle's attempts to control his transformation while dealing with the chaotic situations Mr. Pride creates in his personal and professional life. The narrative culminates in a series of comedic misunderstandings and physical comedy routines as the two personalities battle for control, ultimately resolving in a humorous fashion typical of silent era comedies.

Director

Scott PembrokeAbout the Production

This was one of several comedy shorts Stan Laurel made for producer Joe Rock before teaming with Oliver Hardy. The film was produced quickly on a tight schedule, typical of comedy shorts of the period. The transformation effects were achieved through simple camera tricks and editing techniques rather than sophisticated special effects. The title was deliberately misspelled ('Pyckle' instead of 'Jekyll') to avoid copyright issues while still making the parody clear to audiences.

Historical Background

Dr. Pyckle and Mr. Pride was produced during the golden age of silent comedy in Hollywood, a period when short films were the primary format for comedy entertainment. The mid-1920s saw the rise of parody films that took popular literary works and gave them comedic twists, capitalizing on audience familiarity with the source material. This film came at a time when Stan Laurel was still establishing his individual identity in American cinema before his legendary partnership with Oliver Hardy would begin in 1926. The film industry was rapidly evolving, with studios like Hal Roach and independent producers like Joe Rock competing for audience attention with increasingly sophisticated comedy shorts. The Jekyll and Hyde story had been adapted multiple times for the screen, most notably in the 1920 John Barrymore version, making it ripe for parody.

Why This Film Matters

While not as historically significant as Laurel's later work with Oliver Hardy, Dr. Pyckle and Mr. Pride represents an important transitional phase in comedy cinema history. The film demonstrates the popular trend of literary parody in silent comedy, showing how filmmakers adapted cultural touchstones for comedic effect. It serves as a valuable document of Stan Laurel's development as a performer, showcasing the elements of his comedy style that would later make him famous. The film is part of the broader tradition of transformation comedy that would continue throughout cinema history, influencing later films that played with dual personalities. Its existence helps film historians understand the evolution of American comedy and the development of one of cinema's most beloved comedy duos.

Making Of

The production of Dr. Pyckle and Mr. Pride took place during a pivotal period in Stan Laurel's career when he was transitioning from being a supporting player to establishing himself as a comedy star. Producer Joe Rock had signed Laurel to a contract and was actively developing his screen persona through a series of short comedies. Director Scott Pembroke, who had extensive experience in comedy filmmaking, worked closely with Laurel to develop the physical gags and visual humor that would later become hallmarks of Laurel and Hardy films. The transformation scenes were shot using simple but effective techniques including jump cuts and costume changes filmed in rapid succession. The film was shot on a tight schedule, likely completing production in just 2-3 days, which was typical for comedy shorts of this era. The production team took advantage of existing sets and locations to keep costs down while maximizing visual variety.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Walter Lundin utilized standard techniques for comedy shorts of the era, with clear, bright lighting to emphasize the visual gags and physical comedy. The camera work was straightforward, focusing on capturing Laurel's performance and the transformation sequences effectively. The film employed medium shots and close-ups to highlight facial expressions during the transformation scenes, a technique borrowed from the more serious horror adaptations of the Jekyll and Hyde story. The visual style was clean and simple, ensuring that the comedy remained the focus rather than elaborate cinematographic techniques.

Innovations

The film's main technical achievement was its creative use of simple editing techniques to create the transformation effects without the benefit of modern special effects. The production team used jump cuts, quick costume changes, and strategic camera placement to suggest the transformation from Dr. Pyckle to Mr. Pride. While not technically groundbreaking compared to the more sophisticated effects in serious horror films of the era, these techniques were effective for the comedy context and demonstrated the ingenuity of filmmakers working within the constraints of silent cinema technology.

Music

As a silent film, Dr. Pyckle and Mr. Pride would have been accompanied by live musical accompaniment during theatrical screenings. The score would typically have been provided by the theater's organist or pianist, using standard compilation music appropriate to the action on screen. For the transformation scenes, dramatic music would have been used for comedic contrast, while lighter, more whimsical music would accompany the slapstick sequences. No original composed score exists for this film, as was typical for comedy shorts of this period.

Famous Quotes

(As silent film, dialogue was conveyed through intertitles. Specific intertitle texts from this film are not widely documented in available sources.)

Memorable Scenes

- The transformation sequence where Stan Laurel changes from Dr. Pyckle to Mr. Pride using simple camera tricks and costume changes

- The scene where Mr. Pride causes chaos in a formal setting, contrasting with Dr. Pyckle's timid nature

- The final confrontation between the two personalities as they battle for control

Did You Know?

- This film was released before Stan Laurel's famous partnership with Oliver Hardy was established

- The title is a deliberate parody of 'Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde' with misspellings to avoid copyright issues

- Director Scott Pembroke directed numerous Stan Laurel solo films before Laurel and Hardy became a team

- The film was produced by Joe Rock, who was instrumental in developing Stan Laurel's solo career

- This was one of over 40 solo comedy shorts Stan Laurel made between 1921 and 1926

- The transformation sequence used simple editing techniques rather than the more complex effects used in serious horror films of the era

- Julie Leonard, the female lead, appeared in several other Laurel comedies during this period

- The film was part of a series of literary parodies that were popular in silent comedy

- Syd Crossley, who plays a supporting role, was a British comedian who worked in American films

- The film's running time of 20 minutes was standard for comedy shorts of the mid-1920s

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception for Dr. Pyckle and Mr. Pride was generally positive, with trade publications like Variety and Motion Picture News noting the film's clever parody elements and Laurel's comedic timing. Critics of the era appreciated the film's take on the popular Jekyll and Hyde story, though some felt the premise stretched thin over the two-reel format. Modern critics and film historians view the film primarily as a historical curiosity, important for understanding Laurel's early career and the development of silent comedy. The film is often cited in discussions of Laurel's pre-Hardy work and as an example of literary parody in silent cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences of 1925 generally received the film well, particularly enjoying Laurel's physical comedy and the familiar parody of a well-known story. The film performed adequately in theaters as part of comedy short programs, though it didn't achieve the lasting popularity of some other Laurel solo films. Modern audiences who have seen the film, primarily through film festival screenings and archive presentations, tend to view it with historical interest, appreciating it as a precursor to the more famous Laurel and Hardy comedies that would follow.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1920 film)

- The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (novel by Robert Louis Stevenson)

- Other silent comedy shorts of the era

This Film Influenced

- Later Laurel and Hardy transformation gags

- Various comedy films that parodied horror tropes

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is believed to be partially preserved, though complete copies are rare. Some archives hold fragments or incomplete versions of the film. The Library of Congress and other film preservation organizations may hold elements of this film, but a fully restored, complete version is not widely available to the public. Like many silent comedy shorts, the film has suffered from the degradation common to nitrate film stock of the era.