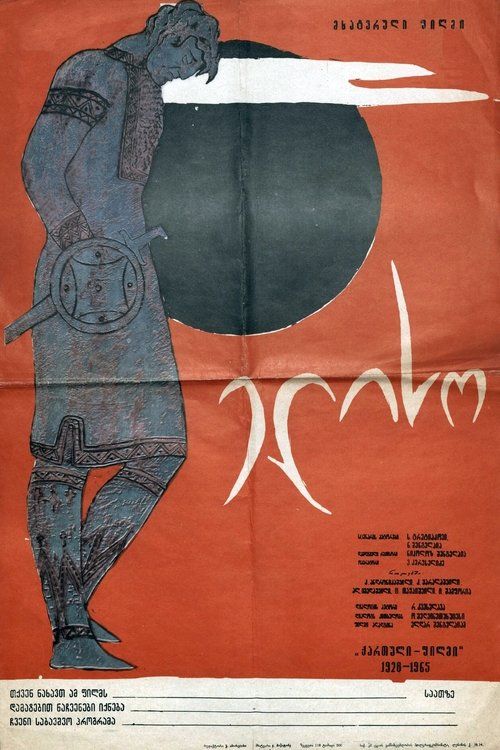

Eliso

Plot

Set in Georgia in 1864 during the Russian Empire's expansion into the Caucasus, 'Eliso' tells the tragic story of forced ethnic cleansing through the lens of a doomed romance. The film follows Eliso, a beautiful young Muslim Georgian woman from the Khevsureti region, who falls deeply in love with Vazha, a Christian Georgian from a neighboring village. As their forbidden romance blossoms, the Tsarist regime, using Cossack forces, begins the brutal forced resettlement of Muslim Georgians to Turkey, a historical event known as muhajirism, designed to seize their ancestral lands. Eliso's family and community face the impossible choice between abandoning their homeland, converting to Christianity, or facing violent expulsion. The film culminates in the heart-wrenching separation of the lovers as Eliso and her family are forced into exile, with Vazha desperately trying to save her from her tragic fate.

About the Production

The film was shot on location in the remote mountainous regions of Georgia, which presented significant logistical challenges for the cast and crew. Director Nikoloz Shengelaia insisted on authentic locations to capture the raw beauty and harsh reality of the Caucasus mountains. The production involved local villagers as extras, many of whom were descendants of the actual historical figures depicted in the story. The film utilized innovative camera techniques for its time, including extensive location shooting and dramatic mountain sequences that were technically difficult to achieve with 1920s equipment.

Historical Background

'Eliso' was produced during a complex period in Soviet cultural history, coinciding with the New Economic Policy (NEP) era that allowed for relative artistic freedom before the strict socialist realism mandates of the 1930s. The film's subject matter—the 1864 forced migration of Muslim Georgians by the Tsarist regime—resonated deeply with contemporary audiences who had experienced recent political upheavals and cultural suppression. The timing was significant as it came just a few years after the 1924 August Uprising in Georgia, a failed anti-Soviet rebellion that resulted in brutal repression. By focusing on historical oppression under the Russian Empire, the film could indirectly comment on contemporary issues while navigating Soviet censorship. The late 1920s also saw the emergence of distinct national cinemas within the Soviet Union, with 'Eliso' representing the flowering of Georgian cinematic identity before Stalin's cultural crackdown would severely limit such expressions.

Why This Film Matters

'Eliso' stands as a cornerstone of Georgian cinema and a vital document of national cultural identity. The film played a crucial role in preserving and promoting Georgian history, traditions, and language during a period of intense Russification and Soviet cultural homogenization. Its sympathetic portrayal of Muslim Georgians helped bridge religious and cultural divides within Georgian society, presenting a unified national identity that transcended religious differences. The film's visual language, incorporating traditional Georgian motifs, landscapes, and cultural practices, created a cinematic blueprint for future Georgian filmmakers. Internationally, 'Eliso' was among the first films from the Caucasus region to gain recognition for its artistic merit, introducing global audiences to the unique cultural heritage of Georgia. The film continues to be studied in film schools worldwide as an example of how national cinema can flourish under restrictive political conditions while maintaining artistic integrity and cultural authenticity.

Making Of

The production of 'Eliso' was a monumental undertaking for the young Georgian film industry. Director Nikoloz Shengelaia, working with cinematographer Giorgi Firtskhelava, pioneered new techniques for filming in extreme mountain conditions. The cast and crew spent months in remote villages, living among local communities to achieve authenticity. Kohkta Karalashvili, who played Eliso, underwent extensive preparation including learning traditional mountain dialects and customs. The film's most challenging sequence involved a dramatic mountain chase scene where the crew had to construct temporary platforms on cliff faces to mount their cameras. Despite limited resources, the production achieved remarkable visual poetry through innovative use of natural light and landscape. The film's emotional intensity was enhanced by Shengelaia's method of having actors live their roles continuously throughout the extended shoot, creating genuine emotional connections that translated powerfully to the screen.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Eliso,' executed by Giorgi Firtskhelava, represents a landmark achievement in silent film visual artistry. The film makes masterful use of the dramatic Caucasus mountain landscape, employing sweeping panoramic shots that establish both the beauty and isolation of the setting. Firtskhelava pioneered techniques for filming in extreme mountain conditions, using natural light to create stark contrasts between the harsh environment and intimate human moments. The camera work emphasizes vertical composition, with characters often shown against towering mountain peaks that symbolize both freedom and entrapment. The film features innovative tracking shots through mountain passes and dramatic high-angle perspectives that enhance the epic scale of the story. The visual poetry of the film is enhanced by careful composition that incorporates traditional Georgian architectural elements and cultural motifs. The cinematography achieves a rare balance between documentary-like authenticity and romantic visual expression, creating images that remain etched in viewers' memories long after the film ends.

Innovations

'Eliso' showcased several technical innovations that were groundbreaking for Soviet cinema of the late 1920s. The film's most significant technical achievement was its successful execution of complex location shooting in remote mountainous terrain, which required the development of portable camera equipment and innovative transportation methods for the heavy film gear. The production team engineered special camera mounts and stabilization devices to achieve smooth tracking shots on uneven mountain paths. The film employed advanced lighting techniques for its time, using reflectors and diffusers to control harsh natural light at high altitudes. The editing, supervised by Shengelaia himself, featured sophisticated cross-cutting between parallel action sequences, creating dramatic tension that was innovative for the period. The film's special effects, particularly in the mountain chase sequences, utilized creative matte work and forced perspective to enhance the sense of scale and danger. The preservation of the film's visual quality through multiple generations of copies represents another technical achievement, with original nitrate elements carefully maintained by Georgian film archives.

Music

The original musical score for 'Eliso' was composed by Iona Tuskia, who ingeniously blended traditional Georgian folk melodies with classical orchestral arrangements typical of silent film accompaniment. The score prominently featured instruments native to Georgian mountain regions, including the panduri (a traditional string instrument) and various folk flutes, creating an authentic soundscape that enhanced the film's cultural specificity. Tuskia incorporated variations of traditional Georgian polyphonic singing, particularly in scenes depicting community life and cultural rituals. The music evolved dramatically with the narrative, shifting from pastoral folk themes during the romance sequences to ominous, militaristic motifs during the forced migration scenes. The original score was performed live in theaters during initial screenings, with varying regional orchestras adapting the music to local resources. Modern restorations of the film have featured newly recorded interpretations of Tuskia's score by contemporary Georgian musicians, maintaining the cultural authenticity while utilizing modern recording technology.

Famous Quotes

Our mountains may be taken from us, but they will remain in our hearts forever.

Love knows no religion when it knows the truth of the heart.

To leave one's homeland is to die while still breathing.

In the eyes of God, we are all children of this same earth.

They can force our bodies from these mountains, but not our souls.

Memorable Scenes

- The mountain chase sequence where Eliso and Vazha flee through treacherous cliff paths, filmed with breathtaking cinematography that captures both the beauty and danger of the Caucasus landscape.

- The heartbreaking farewell scene as Eliso's family prepares for exile, with the entire village gathering in a silent, emotional procession that conveys the weight of cultural loss.

- The secret meeting between Eliso and Vazha by the mountain spring, where their forbidden love is expressed through subtle gestures and meaningful glances, showcasing the power of silent film performance.

- The confrontation scene between the Cossack commander and the village elders, where the brutal reality of forced migration is revealed through powerful dialogue and tense composition.

- The final scene of Eliso looking back at her homeland as she leaves, a long shot that captures her silhouette against the mountains, becoming an iconic image of exile and loss.

Did You Know?

- The film is based on the 1882 short story 'Eliso' by renowned Georgian writer Akaki Tsereteli, making it a literary adaptation of national significance

- Director Nikoloz Shengelaia was only 26 years old when he made this masterpiece, which would become his most celebrated work

- The film was considered controversial in the Soviet Union for its sympathetic portrayal of religious themes and its critique of Russian imperial policies

- Despite being a Soviet production, the film emphasizes Georgian national identity and culture, which was unusual for the period of increasing Soviet centralization

- The actress playing Eliso, Kohkta Karalashvili, was discovered by the director in a Tbilisi theater and this was her film debut

- The film's depiction of the forced migration of Muslim Georgians (muhajirism) was one of the first cinematic treatments of this historical tragedy

- The mountain sequences were filmed at altitudes exceeding 2,500 meters, requiring the crew to carry heavy camera equipment by hand and mule

- The film was temporarily banned in some Soviet republics for its 'nationalist' elements but was later rehabilitated and recognized as a classic

- Original nitrate prints of the film were nearly lost during World War II but were preserved through the efforts of Georgian film archivists

- The film's score was composed by Iona Tuskia, who incorporated traditional Georgian folk melodies into the orchestral accompaniment

What Critics Said

Upon its release, 'Eliso' received widespread critical acclaim both within the Soviet Union and internationally. Soviet critics praised the film's technical achievements and emotional power, with particular admiration for Shengelaia's innovative direction and the powerful performances of the lead actors. The influential Soviet film magazine 'Kino' hailed it as 'a triumph of Georgian national cinema' and 'a masterpiece of silent film art.' International critics at European film festivals were impressed by the film's visual poetry and its universal themes of love and oppression despite being rooted in specific Georgian history. Contemporary film historians consider 'Eliso' ahead of its time in its sophisticated visual storytelling and its nuanced approach to complex historical and cultural themes. Modern critics have reevaluated the film as an important example of resistance cinema, noting how it managed to critique imperial power while celebrating national identity within the constraints of the Soviet system.

What Audiences Thought

Georgian audiences embraced 'Eliso' with tremendous enthusiasm, with the film running for months in Tbilisi theaters and drawing record crowds throughout Georgia. The film's emotional resonance was particularly strong among viewers who had family connections to the historical events depicted, with many reporting deeply personal responses to the story of forced migration and cultural loss. The film became a cultural touchstone, with lines and scenes entering popular Georgian culture and being referenced for decades. Despite language barriers, the film found appreciative audiences in other Soviet republics and even achieved limited distribution in Europe, where its universal themes transcended cultural boundaries. The love story between Eliso and Vazha particularly captivated audiences, becoming one of the most celebrated romantic narratives in Soviet cinema. The film's reputation has only grown over time, with modern Georgian audiences still considering it an essential part of their cultural heritage and cinematic tradition.

Awards & Recognition

- Recognized as one of the top 100 Georgian films of all time by the Georgian National Film Center

- Honored at the 1928 Soviet Film Festival in Moscow for artistic achievement

- Received special commendation from the Georgian Academy of Arts and Sciences (1929)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The literary works of Akaki Tsereteli (original story author)

- German Expressionist cinema (visual style influence)

- Soviet montage theory (editing techniques)

- Georgian epic poetry and folk traditions

- The romantic tradition of 19th-century literature

- Georgian medieval fresco painting (visual composition)

This Film Influenced

- Twenty-Four Eyes (1954) - similar themes of cultural oppression

- The Color of Pomegranates (1969) - Georgian poetic cinema tradition

- Repentance (1984) - Georgian historical allegory

- Mimino (1977) - Georgian cultural identity themes

- Since Otar Left (2003) - Georgian family and cultural continuity

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved through the efforts of the Georgian National Film Archives, though some degradation has occurred over time. Original nitrate elements were carefully transferred to safety stock in the 1970s. A comprehensive restoration was completed in 2005 by the Georgian National Film Center in collaboration with international film preservation organizations. The restored version premiered at the Tbilisi International Film Festival and has since been screened at various classic film festivals worldwide. While some scenes show signs of nitrate deterioration, the majority of the film remains in good condition with clear image quality. The Georgian Film Archives continues to maintain the original elements and has created digital backups for long-term preservation. The restoration work has been praised for maintaining the film's original visual aesthetic while improving stability for future screenings.