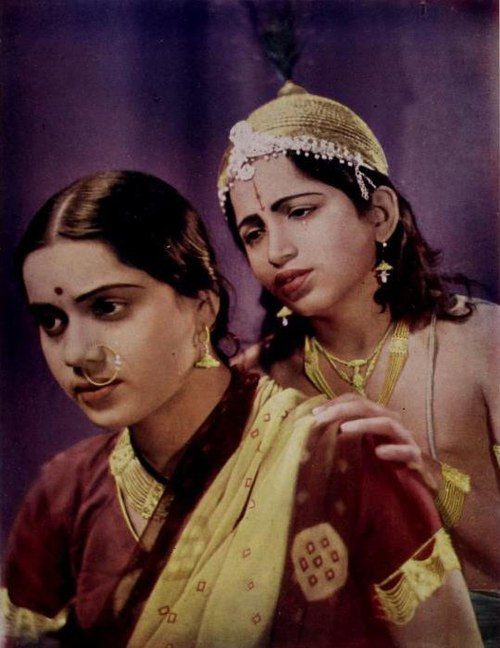

Gopal Krishna

Plot

Gopal Krishna (1938) is a mythological drama depicting the childhood adventures of Lord Krishna in the city of Gokul. The film follows the young Krishna (played by Ram Marathe) as he uses his divine powers to protect the people of Gokul from the tyrannical King Kamsa (Ganpatrao). When Kamsa sends his general Keshi (Haribhau) in disguise to capture Krishna, the divine child cleverly defeats him. In a significant departure from traditional legends, where Indra causes floods, this version shows Kamsa unleashing rain and floods upon the city, prompting Krishna to miraculously lift the Govardhan mountain to shelter the entire population. The film culminates in Krishna's ultimate victory over evil, reinforcing themes of divine intervention and the triumph of good over evil.

About the Production

This film was produced by Prabhat Film Company, one of India's most prestigious early film studios. The production utilized elaborate sets and costumes typical of Prabhat's mythological productions. Special effects for the mountain-lifting scene were considered innovative for its time, using clever camera work and miniature models. The film was shot during the golden era of Prabhat Studios when they were known for their technical excellence and artistic ambition.

Historical Background

Gopal Krishna was produced in 1938, during the late colonial period in India when the Indian film industry was experiencing rapid growth and technical advancement. This era saw the emergence of major studios like Prabhat, which were competing to produce increasingly ambitious films. The late 1930s was also a period of rising Indian nationalism, and mythological films like Gopal Krishna often carried subtle undertones of resistance against colonial rule by celebrating indigenous culture and religious traditions. The film industry was transitioning from silent films to talkies, and by 1938, sound technology had become sophisticated enough to accommodate elaborate musical numbers and complex sound effects. Prabhat Studios, where this film was made, was at the forefront of this technical revolution and was known for its progressive approach to filmmaking, including employing women in key technical roles.

Why This Film Matters

Gopal Krishna represents an important milestone in the development of Indian mythological cinema, a genre that has remained popular throughout the history of Indian filmmaking. The film contributed to the codification of visual language for depicting Hindu deities on screen, establishing conventions that would influence countless subsequent films. Its departure from traditional mythology by making Kamsa rather than Indra responsible for the floods demonstrates how filmmakers adapted ancient stories to contemporary dramatic needs. The film also exemplifies the role of cinema in preserving and popularizing religious and cultural traditions during a period of social change. For audiences in the 1930s, such films served as both entertainment and moral education, reinforcing traditional values while showcasing Indian cultural heritage. The success of Gopal Krishna and similar mythologicals helped establish the commercial viability of big-budget productions in Indian cinema.

Making Of

The making of Gopal Krishna was a monumental undertaking for Prabhat Studios, requiring extensive research into Hindu mythology and careful adaptation of the source material from Bhagvat and Vishnu Purana. Director Vishnupant Govind Damle, known for his meticulous attention to detail, worked closely with the art department to create authentic period costumes and elaborate sets representing ancient Gokul. The casting of Ram Marathe as Krishna was particularly significant, as he brought both acting talent and classical singing expertise to the role. The famous Govardhan mountain lifting scene required innovative camera techniques and the use of forced perspective to create the illusion of a young boy lifting a massive mountain. Shanta Apte, already a star at Prabhat, contributed significantly to the film's musical success. The production team faced challenges in creating realistic flood effects, ultimately using a combination of water tanks, miniatures, and clever editing to achieve the desired impact.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Gopal Krishna was handled by the skilled technicians at Prabhat Studios, known for their innovative camera work and lighting techniques. The film employed dramatic lighting to create divine auras around Krishna and other supernatural elements. For the flood sequences, the cinematography used multiple camera angles and varying shot sizes to create a sense of chaos and impending disaster. The famous Govardhan mountain lifting scene utilized forced perspective and clever camera positioning to create the illusion of a young boy lifting an enormous mountain. The film also featured elaborate tracking shots during the dance sequences and battle scenes, demonstrating the technical sophistication of Prabhat's camera department. The black and white photography made excellent use of contrast and shadow to enhance the mythological atmosphere, particularly in scenes depicting the conflict between good and evil.

Innovations

Gopal Krishna showcased several technical achievements that were remarkable for Indian cinema in 1938. The film's special effects, particularly the sequence showing Krishna lifting the Govardhan mountain, demonstrated innovative use of miniatures, matte paintings, and forced perspective photography. The flood sequences required elaborate water tank facilities and sophisticated editing techniques to create realistic disaster scenes. The sound recording and mixing for the musical numbers was particularly advanced, allowing for clear reproduction of classical vocals and orchestral arrangements. The film's makeup and prosthetics for depicting divine characters and demons were considered state-of-the-art for the period. The production also featured elaborate costume design and set construction that set new standards for mythological films. The cinematography employed complex camera movements and lighting techniques that were ahead of their time in Indian cinema.

Music

The music for Gopal Krishna was composed by Keshavrao Bhole, one of the pioneers of Indian film music who was known for blending classical Indian traditions with cinematic requirements. The soundtrack featured numerous devotional songs (bhajans) that became extremely popular with audiences. Ram Marathe, who played Krishna, was a trained classical singer and performed several songs in the film, lending authenticity to the musical sequences. Shanta Apte, renowned for her powerful voice, also contributed significantly to the soundtrack. The music incorporated traditional ragas and folk melodies associated with Krishna's life in Vrindavan. The songs were not merely entertainment but served to advance the narrative and express the emotional states of the characters. The sound design for the flood scenes and battle sequences was considered innovative for its time, using creative techniques to simulate natural disasters and divine interventions.

Famous Quotes

"Mai toh Nath hoon, tumhare paas jo kuch hai woh mera hi hai" (I am the Lord, whatever you have is mine alone) - Krishna

"Dharm ki jeet hamesha hoti hai, adharm ka ant zaroor hota hai" (Righteousness always wins, evil definitely meets its end) - Narrator

"Bhakti aur vishwas se koi bhi parvat chhota ho jata hai" (With devotion and faith, even mountains become small) - Krishna

Memorable Scenes

- The iconic Govardhan mountain lifting sequence where young Krishna raises the mountain on his little finger to protect the people of Gokul from devastating floods, featuring innovative special effects for 1938

- The dramatic confrontation between Krishna and Keshi, Kamsa's disguised general, showcasing the divine child's wisdom and supernatural powers

- The elaborate dance sequence in Vrindavan with Krishna and the gopis, featuring classical Indian dance forms and colorful costumes

- The birth scene of Krishna with divine lights and celestial music, establishing his divine nature from the beginning

- The final battle sequence where Krishna confronts King Kamsa, incorporating dramatic fight choreography and moral resolution

Did You Know?

- Director Vishnupant Govind Damle was one of the founding members of the legendary Prabhat Film Company

- Shanta Apte, who played a key role, was one of the highest-paid actresses of the 1930s and known for her singing prowess

- The film featured Ram Marathe, a noted classical singer, in the title role of young Krishna

- This was one of the early films to depict the Govardhan mountain lifting sequence on screen

- The film's music was composed by Keshavrao Bhole, a pioneer of Marathi film music

- Prabhat Studios was known for investing heavily in mythological subjects during this period

- The film's special effects for the flood scenes were considered groundbreaking for Indian cinema in 1938

- This was one of the last films directed by Damle before his death in 1945

- The film was released in both Marathi and Hindi versions to reach wider audiences

- The production involved hundreds of extras for the crowd scenes depicting the people of Gokul

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Gopal Krishna for its technical achievements and faithful representation of Hindu mythology. The film was particularly lauded for its impressive special effects, especially the Govardhan mountain lifting sequence, which was considered a marvel of Indian cinema in 1938. Critics also appreciated the musical contributions of Keshavrao Bhole and the performances of the lead actors, particularly Ram Marathe's portrayal of the young Krishna. The film was noted for its elaborate production values and the artistic vision of director Vishnupant Govind Damle. Modern film historians regard Gopal Krishna as an exemplary work of early Indian mythological cinema, demonstrating the technical and artistic capabilities of Prabhat Studios during its golden era. The film is often cited in academic studies of Indian cinema as an important example of how traditional religious narratives were adapted for the medium of film.

What Audiences Thought

Gopal Krishna was received with great enthusiasm by audiences across India, particularly in Maharashtra where it was produced. The film's combination of religious themes, spectacular visuals, and melodious music appealed to family audiences of all ages. The performance of Ram Marathe as Krishna was especially popular with children, while adults appreciated the film's spiritual and moral dimensions. The film ran successfully in theaters for extended periods, indicating strong word-of-mouth promotion. Its success contributed to the continued popularity of mythological subjects in Indian cinema throughout the 1940s and beyond. The film's songs became popular and were often sung in households long after the theatrical run ended. Audience response to the special effects, particularly the mountain lifting scene, was particularly enthusiastic, with many viewers reporting being genuinely moved by the spectacle.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Traditional Hindu mythology from Bhagavat Purana

- Vishnu Purana scriptures

- Earlier Prabhat Studios mythological productions

- Traditional Indian temple art and sculpture

- Classical Indian dance and music traditions

- Folk theater traditions of Maharashtra

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent Indian mythological films about Krishna

- Later Prabhat Studios productions

- Regional cinema adaptations of Krishna stories

- Television serials about Krishna's life

- Modern reinterpretations of Hindu mythology in cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of Gopal Krishna (1938) is uncertain, as is the case with many early Indian films. While Prabhat Films maintained archives, many prints from this era were lost due to the nitrate film degradation and inadequate storage conditions during the mid-20th century. Some fragments or partial prints may exist in the National Film Archive of India (NFAI) or private collections, but a complete, restored version may not be available. The film's historical importance has led to ongoing efforts by film preservationists to locate and restore surviving elements. Some audio recordings of the film's songs have survived and are preserved in various archives.