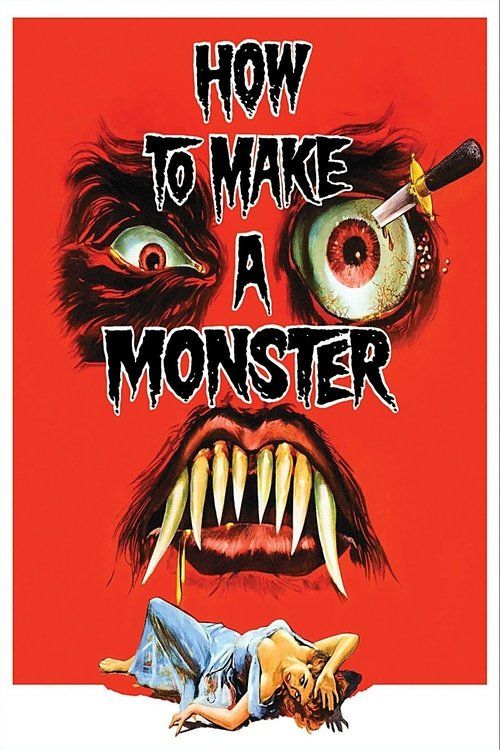

How to Make a Monster

"He Creates Monsters For The Movies... But Now He's Making Them For Real!"

Plot

When veteran makeup artist Pete Dumond is abruptly fired from American International Studios after the new management decides to discontinue horror films, he becomes consumed by revenge. Using his expertise in monster makeup, Dumond develops a special chemical compound that, when activated by a specific frequency, transforms actors wearing his creations into actual monsters. He convinces two young actors, Tony Mantell and Gary Droz, to participate in what they believe is a final screen test, but instead uses them as instruments of murder against the studio executives who wronged him. As the transformed monsters begin running amok through the studio lot, Dumond's carefully planned revenge spirals into chaos, ultimately leading to his downfall when the monsters turn on their creator.

About the Production

The film was shot in just seven days on a shoestring budget, typical of AIP's production methods. The monster makeup effects were created by Paul Blaisdell, who was renowned for his work on other AIP monster films. The production utilized existing sets from previous AIP horror productions to save costs. The film's self-referential nature about making monster movies made it unique among its contemporaries.

Historical Background

Released in 1959, 'How to Make a Monster' emerged during the golden age of American horror cinema and the peak of the monster movie craze. This period saw the rise of drive-in theaters and the teenage market as the primary audience for horror films. The late 1950s also marked a significant shift in Hollywood, with traditional studios losing ground to independent producers like American International Pictures. The film's meta-commentary on the film industry reflected growing tensions between old Hollywood veterans and the new generation of filmmakers and studio executives. Additionally, the Cold War era's fascination with transformation and hidden threats found expression in horror films like this one, where ordinary people could become monstrous through scientific means.

Why This Film Matters

As one of the earliest meta-horror films, 'How to Make a Monster' pioneered the concept of horror movies about horror movies. Its self-referential approach predates more famous examples like 'Scream' by decades, establishing a template for films that comment on their own genre. The movie also serves as a time capsule of 1950s monster movie production, offering a behind-the-scenes look at the practical effects techniques that would soon be replaced by more sophisticated methods. Its portrayal of the film industry's disposable treatment of creative talent resonated with many artists in Hollywood and influenced later films about the business of entertainment.

Making Of

The production faced significant challenges due to its extremely tight schedule and limited budget. Director Herbert L. Strock had to complete the entire film in just one week, often shooting 12-14 hours per day. The monster transformation scenes were particularly difficult to execute, requiring actors to sit for hours in makeup chair while Paul Blaisdell applied his elaborate prosthetics. The film's self-referential quality was somewhat accidental - the script was written quickly to capitalize on AIP's existing monster movie sets and makeup effects. The studio lot scenes were filmed at the actual AIP facilities, giving the film an authentic behind-the-scenes feel. Many of the background actors were actual AIP employees, adding to the film's documentary-like quality in certain scenes.

Visual Style

The cinematography, handled by Gerald Perry, utilized the high-contrast black and white style typical of AIP productions. The film employed dramatic lighting techniques to enhance the horror atmosphere, particularly in the transformation scenes where shadows were used to conceal the limitations of the makeup effects. The camera work was straightforward but effective, with close-ups used extensively during the makeup application scenes to emphasize the transformation process. The studio lot scenes were shot with a documentary-like realism, contrasting with the more stylized horror sequences.

Innovations

The film's most significant technical achievement was Paul Blaisdell's monster makeup effects, which were innovative for their time despite the budget constraints. The transformation sequences used a combination of makeup, camera tricks, and editing techniques to create the illusion of actors becoming monsters. The special frequency device was created using practical electronic effects that were convincing enough for the film's purposes. The production also pioneered the use of existing studio sets and props from previous films to create a cohesive visual narrative about the movie industry.

Music

The film's score was composed by Albert Glasser, who was known for his work on numerous low-budget science fiction and horror films. Glasser incorporated Theremin elements to create an otherworldly atmosphere, particularly in scenes involving the activation frequency. The music featured dramatic brass sections and percussion during action sequences, while using more subtle string arrangements for the behind-the-scenes scenes. The soundtrack also included several diegetic musical moments, such as when the characters are watching monster movies being filmed.

Famous Quotes

I create monsters for the movies, but now I'm making them for real!

They think they can just throw away twenty years of my life like yesterday's newspaper!

This isn't makeup anymore, boys. This is the real thing!

In this business, you're only as good as your last monster.

They wanted horror? I'll give them horror they'll never forget!

Memorable Scenes

- The first transformation scene where Tony Mantell gradually becomes a werewolf-like creature under the influence of the special frequency, featuring impressive makeup effects for the budget.

- The climactic sequence where the transformed monsters rampage through the studio lot, destroying sets and equipment in a chaotic finale.

- Pete Dumond's laboratory scene where he demonstrates his chemical compound and explains his revenge plan to his assistant.

- The behind-the-scenes footage of monster makeup being applied, offering a genuine look at 1950s special effects techniques.

Did You Know?

- The film was originally titled 'The Face of Death' before AIP changed it to 'How to Make a Monster' to capitalize on the 'how-to' trend of the era.

- Paul Blaisdell's monster makeup creations were so effective that some audience members believed they were seeing real monsters on screen.

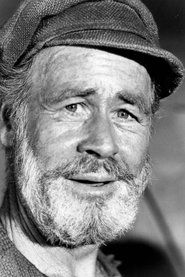

- Robert Harris, who played Pete Dumond, was primarily a stage actor and this was one of his few leading film roles.

- The film was released as a double feature with 'The Brain That Wouldn't Die' in many markets.

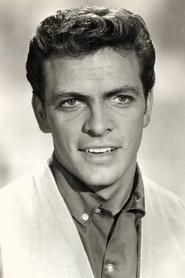

- Gary Conway, who played Tony Mantell, later became a television star in shows like 'Burke's Law' and 'Land of the Giants'.

- The special frequency used to activate the monsters was created using a Theremin, an electronic musical instrument popular in sci-fi films of the era.

- The film's climax was shot in a single marathon session that lasted 18 hours.

- AIP producer Samuel Z. Arkoff reportedly came up with the concept after an argument with a makeup artist on a previous film.

- The monster masks were reused from earlier AIP films including 'The She-Creature' and 'It Conquered the World'.

- The film's success led to AIP greenlighting more meta-horror films about the movie industry.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics gave the film mixed reviews, with many dismissing it as typical B-movie fare despite acknowledging its clever premise. Variety noted that 'the film rises above its limitations through an inventive script and effective makeup effects.' Modern critics have reassessed the film more favorably, with many horror historians recognizing its importance as an early example of meta-horror. Tim Lucas of Video Watchdog praised the film's 'surprisingly sophisticated commentary on the film industry' and called it 'one of AIP's most intelligent productions.' The film is now regarded as a cult classic among horror enthusiasts.

What Audiences Thought

Upon its release, the film performed solidly at drive-in theaters and midnight shows, particularly appealing to teenage audiences who were AIP's primary demographic. The transformation scenes were especially popular with audiences, who were impressed by the practical effects. In the years since, the film has developed a strong cult following, with horror fans appreciating its self-aware humor and behind-the-scenes perspective. Modern audiences often cite it as a favorite example of 1950s monster cinema, with many considering it superior to many of its contemporaries due to its clever premise.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier Universal monster movies

- Film noir revenge narratives

- AIP's previous monster films

- The 'body horror' subgenre

- German Expressionist cinema

This Film Influenced

- The Blob (1958) - similar monster transformation themes

- The Little Shop of Horrors (1960) - similar low-budget horror comedy approach

- The Terror (1963) - similar AIP production methods

- Scream (1996) - meta-horror elements

- New Nightmare (1994) - horror about horror filmmaking

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved in the American Genre Film Archive and has undergone digital restoration. Original 35mm elements still exist in good condition, and the film has been released on Blu-ray by MGM with a restored transfer. The restoration work has significantly improved the image quality over previous VHS and DVD releases, making the makeup effects and cinematography more visible than in earlier home media versions.