Judith and Holophernes

Plot

Set in ancient times during the Assyrian siege of Bethulia, the film follows the beautiful widow Judith who devises a daring plan to save her people. With the city facing starvation and surrender, Judith volunteers to venture into the enemy camp of the feared Assyrian general Holofernes. Using her beauty and charm, she seduces the powerful general and gains his trust during a lavish banquet. When Holofernes falls into a drunken stupor, Judith retrieves his sword and beheads him, carrying his head back to her people in triumph. The Assyrian army, leaderless and terrified, flees in panic, and Bethulia is saved through Judith's courageous sacrifice and cunning strategy.

About the Production

This was one of the last major Italian silent epics before the transition to sound cinema. The production faced significant challenges due to the declining silent film market and the impending transition to sound technology. The elaborate historical costumes and sets were typical of Italian epic productions of the 1920s, though budget constraints were evident compared to earlier Italian epics. The film's timing was unfortunate as it was released just as Italian cinema was transitioning to sound, limiting its commercial potential.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a critical moment in Italian and world history. In 1929, Italy was firmly under Fascist rule with Mussolini's regime consolidating power, though the biblical setting allowed the film to avoid direct political entanglement. The Italian film industry was in transition, moving from the golden age of silent epics in the 1910s to the challenges of sound cinema in the 1930s. The late 1920s saw the decline of Italian cinema's international prominence, which had peaked with films like Cabiria (1914). The Great Depression was beginning to affect global economies, impacting film production and distribution worldwide. This period also saw the rise of censorship and state control over cultural production in Fascist Italy, though biblical stories were generally considered safe subjects. The film's release came just months after the 1929 Lateran Treaty between Italy and the Vatican, making biblical themes particularly relevant to Italian audiences.

Why This Film Matters

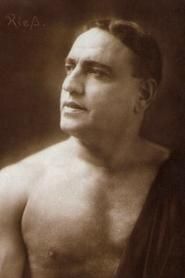

As one of the last major Italian silent epics, 'Judith and Holophernes' represents the end of an era in Italian cinema history. The film exemplifies the Italian tradition of historical and biblical epics that had dominated the country's film output since the early 1910s. Bartolomeo Pagano's final performance marked the end of the career of Italy's first genuine film star, who had helped establish the strongman archetype that would influence cinema worldwide. The biblical story of Judith resonated with contemporary themes of female empowerment and resistance against oppression, though interpreted through the lens of 1920s Italian culture. The film's timing at the transition to sound cinema makes it a valuable document of late silent filmmaking techniques and storytelling methods. The production also reflects the international nature of European cinema in the 1920s, with Russian émigré Jia Ruskaja contributing to Italian cultural production.

Making Of

The production of 'Judith and Holophernes' took place during a transitional period in Italian cinema history. Director Baldassarre Negroni, an experienced filmmaker from the early days of Italian cinema, brought his expertise to this biblical epic. The casting of Bartolomeo Pagano, who had been Italy's biggest film star through his Maciste films in the 1910s and early 1920s, was intended to attract audiences, though by 1929 his star power had diminished. Jia Ruskaja, a Russian émigré dancer, brought authentic movement and grace to the role of Judith. The production faced the typical challenges of late silent films, including the industry's rapid transition to sound technology. The sets and costumes were designed to evoke the ancient biblical setting, though budget constraints limited the scope compared to earlier Italian epics. The beheading scene, central to the story, was handled with the dramatic flair typical of silent cinema, using shadows and camera angles to suggest violence while respecting censorship standards of the era.

Visual Style

The cinematography employed the dramatic lighting and compositional techniques characteristic of late silent cinema. The visual style emphasized chiaroscuro effects, particularly in the crucial beheading scene where shadows and camera angles created dramatic tension without explicit gore. The cinematography utilized the full range of silent film visual storytelling, with expressive close-ups to convey emotion and sweeping shots to establish the historical setting. The camera work shows the influence of German expressionist cinema, particularly in the use of dramatic lighting and angular compositions during tense scenes. The visual approach was conservative compared to more experimental silent films of the era, reflecting the traditional nature of the biblical subject matter and the commercial considerations of a major production.

Innovations

The film employed standard silent era techniques but showed some refinements typical of late 1920s productions. The camera work included more mobile shots than earlier silent films, reflecting technological advances in camera equipment. The lighting techniques were more sophisticated than in earlier Italian epics, showing the influence of international cinema trends. The film's makeup and costume design demonstrated the refinement of silent era techniques for creating historical authenticity on screen. The editing pace was slightly faster than earlier silent epics, reflecting audience expectations that had evolved throughout the 1920s. However, the film did not introduce significant technical innovations, as the industry was focusing its innovation efforts on sound technology rather than silent film techniques.

Music

As a silent film, 'Judith and Holophernes' would have been accompanied by live musical performances during its theatrical run. The original score would have been typical of late silent era biblical epics, featuring dramatic orchestral music that emphasized the story's emotional and dramatic moments. The music would have included romantic themes for Judith's scenes, militaristic motifs for the Assyrian sequences, and suspenseful passages during the beheading sequence. Specific composers for the original score are not documented, though theaters would have used compiled music or commissioned scores from local musicians. The transition to sound cinema meant that this film was among the last to use the traditional silent film music accompaniment system.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, dialogue was conveyed through intertitles and performance. Key moments included Judith's declaration: 'I will go forth to save my people, though it may cost me my life.'

Holofernes' boast: 'No army can withstand the might of Assyria, and no woman can resist the power of Holofernes.'

Judith's prayer: 'Give me strength, O Lord, to do what must be done for the salvation of Bethulia.'

Memorable Scenes

- The banquet scene where Judith gains Holofernes' trust through charm and wit, building tension through subtle glances and gestures

- The dramatic beheading sequence, filmed with shadows and camera angles to suggest violence while maintaining dramatic impact

- Judith's triumphant return to Bethulia with Holofernes' head, celebrated by her people as a savior

- The opening siege sequences establishing the desperate situation of Bethulia under Assyrian attack

- Judith's preparation scene where she dons her finest clothes and jewelry, preparing for her dangerous mission

Did You Know?

- This was Bartolomeo Pagano's final film appearance, ending a career that made him Italy's first major film star through his Maciste character

- The film was released just as Italian cinema was transitioning to sound, contributing to its limited commercial success

- Jia Ruskaja was a Russian-born dancer who had fled to Italy after the Russian Revolution and became a prominent figure in Italian dance and cinema

- The biblical story of Judith and Holofernes was a popular subject in early cinema, with numerous adaptations made in the silent era

- Director Baldassarre Negroni was a prolific filmmaker who had been active since the early 1910s and directed over 100 films in his career

- The film's production coincided with the rise of Fascism in Italy, though the biblical setting avoided direct political commentary

- Despite being a historical epic, the film was made with significantly fewer resources than earlier Italian epics like Cabiria (1914)

- The original Italian title 'Giuditta e Oloferne' follows the Italian tradition of using character names for biblical adaptations

- The film featured elaborate costumes designed to evoke ancient Assyrian and Jewish attire, though historical accuracy was secondary to dramatic effect

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of 'Judith and Holophernes' was mixed to positive, though overshadowed by the industry's transition to sound. Italian critics noted the film's traditional approach to biblical storytelling and praised Pagano's dignified performance in his final role. Some reviewers commented on the film's modest scale compared to earlier Italian epics, though acknowledging the changing economic realities of film production. The performances, particularly Jia Ruskaja's interpretation of Judith, received favorable attention for their dramatic intensity. Modern film historians view the film primarily as a historical artifact marking the end of silent cinema in Italy and the conclusion of Bartolomeo Pagano's influential career. The film is occasionally referenced in studies of biblical adaptations and the history of Italian cinema, though it remains lesser-known than earlier Italian epics.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception in 1929 was modest, as the film competed with the growing excitement around sound cinema. Many viewers attended primarily to see Bartolomeo Pagano's final screen appearance, reflecting the enduring affection for the actor who had created the iconic Maciste character. The biblical subject matter appealed to Italy's predominantly Catholic audience, though the timing during the transition to sound limited its commercial potential. Contemporary reports suggest that audiences appreciated the film's dramatic moments and the spectacle of the historical setting, even if the production values seemed dated compared to new sound films. The film's limited release and subsequent obscurity indicate that it did not achieve significant popular success, though it likely found appreciative audiences among traditionalists who preferred silent cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier Italian silent epics like Cabiria (1914)

- German expressionist cinema of the 1920s

- D.W. Griffith's biblical films

- The tradition of biblical adaptations in early cinema

- Italian historical costume dramas of the silent era

This Film Influenced

- Later biblical epics of the sound era

- Subsequent Judith adaptations in cinema

- Italian historical films of the 1930s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of 'Judith and Holophernes' is uncertain, with many sources suggesting it may be a lost film. Like many Italian silent films, prints may have been lost due to neglect, the nitrate film decomposition common to era, or destruction during World War II. Some archives may hold partial prints or fragments, but a complete version has not been widely available for decades. The film's status as a late silent production during the industry transition may have contributed to its disappearance from archives and collections. Film historians continue to search for copies in European archives and private collections, though the chances of finding a complete print diminish with time.