Kalpana

Plot

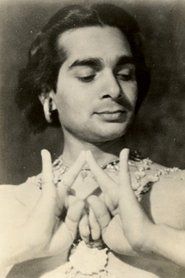

Kalpana (1948) is a pioneering Indian dance film that employs a meta-narrative structure to explore the power of imagination. The story centers on a passionate writer who brings his ambitious screenplay to a skeptical film producer, hoping to sell his vision of a world where art reigns supreme. As the writer vividly narrates his story, the film seamlessly transitions into breathtaking dance sequences that materialize his ideas, featuring Uday Shankar's revolutionary choreography that blends Indian classical dance with modern interpretations. The narrative contrasts the pure, uncommercialized world of the writer's imagination with the pragmatic demands of the film industry, highlighting the eternal struggle between artistic integrity and commercial viability. The film reaches its climax when the producer, initially resistant to the unconventional approach, becomes completely absorbed in the writer's imaginative world, ultimately recognizing the transformative power of art.

Director

About the Production

The production took approximately three years to complete, with extensive time devoted to choreographing and filming complex dance sequences. The film featured over 200 dancers, many of whom were students from Shankar's dance academy. Elaborate sets were designed to create a dreamlike atmosphere complementing the film's themes. The synchronization of camera movements with dance choreography required innovative filming techniques ahead of their time in Indian cinema.

Historical Background

Kalpana was created in a pivotal moment in Indian history, just one year after India gained independence from British rule in 1947. This period marked the beginning of a new era in Indian cinema as filmmakers sought to establish a distinct national identity separate from colonial influences. The film's emphasis on Indian dance forms reflected the broader cultural renaissance happening across the country. The late 1940s saw Indian cinema transitioning from the studio system to independent productions. The film's themes of artistic freedom versus commercial constraints resonated deeply in a nation grappling with questions of cultural authenticity. The international recognition at Cannes came as India was establishing its presence on the world stage. The film's ambitious scope mirrored the optimism of post-independence India.

Why This Film Matters

Kalpana holds a unique place in Indian cinema as one of the earliest attempts to create a purely dance-driven feature film. It represents a crucial moment in documenting Indian dance traditions on celluloid. Uday Shankar's innovative choreography, blending classical Indian dance with contemporary elements, influenced generations of dancers. The film's meta-narrative structure was ahead of its time. It stands as a testament to Uday Shankar's vision of bridging classical and popular art forms. The film's emphasis on imagination carried deeper meaning in newly independent India seeking cultural identity. Despite initial commercial failure, it has gained legendary status among film scholars and dance enthusiasts. The film continues to be studied as a pioneering work that expanded possibilities of both cinema and dance.

Making Of

The making of Kalpana was as ambitious as the film itself. Uday Shankar, already established as a pioneering dancer who had toured internationally, decided to venture into filmmaking to preserve his unique dance style. He poured his personal fortune into the project, building elaborate sets that were architectural marvels. The production faced numerous challenges, including adapting stage choreography for cinema. The collaboration with his brother Ravi Shankar for music was special, representing fusion of two artistic geniuses. Shankar insisted on multiple takes to perfect synchronization between dance and camera, uncommon in 1940s Indian cinema. The production faced financial difficulties, with Shankar mortgaging properties to complete it. Despite challenges, the cast remained dedicated to Shankar's vision. Post-production was equally painstaking, with innovative editing enhancing the dreamlike quality of dance sequences.

Visual Style

The cinematography was revolutionary for its time, employing techniques uncommon in 1940s Indian cinema. Cinematographer D. K. Ambale worked closely with Uday Shankar to create visual language capturing dance fluidity. The film features innovative camera movements following dancers' movements, creating dynamic interplay between performer and camera. Ambale used extensive tracking shots and crane movements to enhance spatial relationships between dancers. The lighting design was noteworthy, using dramatic contrasts to highlight dancers' bodies and create dreamlike atmosphere. The film experimented with multiple camera angles for same dance sequence, allowing dynamic editing maintaining rhythm. The cinematography successfully balanced showcasing full choreography with intimate close-ups capturing emotional expressions.

Innovations

Kalpana was technically groundbreaking for 1948 Indian cinema, introducing several innovations. Its most significant achievement was integrating elaborate dance sequences into narrative cinema, requiring innovative approaches to choreography, cinematography, and editing. The production employed advanced camera techniques including crane shots and tracking movements following dancers across large spaces. Set design was ambitious, featuring movable platforms allowing dynamic choreography. Editing techniques maintaining dance rhythm were innovative. The film experimented with special effects creating surreal sequences reflecting imagination themes. Sound recording techniques capturing music and dance were advanced. Color sequences demonstrated sophisticated use of color enhancing emotional impact. Most importantly, Kalpana established technical template for filming dance influencing Indian cinema for decades.

Music

The soundtrack was composed by young Ravi Shankar, who would later become world-famous as sitar virtuoso. This collaboration resulted in musical score both innovative and rooted in Indian classical traditions. The music blends Indian classical forms with Western orchestral arrangements, creating unique sound complementing fusion choreography. Ravi Shankar incorporated instruments from different Indian regions, creating rich tapestry reflecting cultural diversity. The soundtrack features both instrumental pieces accompanying dance and vocal compositions enhancing emotional narrative. Notably, it avoids typical song-and-dance format, functioning as integral part of choreography. The score uses complex rhythmic patterns mirroring dance movements. The music incorporates folk elements from various states, reflecting Uday Shankar's philosophy of pan-Indian dance vocabulary.

Did You Know?

- Kalpana was the only feature film ever directed by legendary dancer Uday Shankar, making it a unique artifact in Indian cinema history

- The film's title means 'imagination' in Sanskrit and several Indian languages, reflecting its central theme

- Uday Shankar's brother, world-renowned sitarist Ravi Shankar, composed the music for the film at age 28

- The film took nearly three years to complete, with Uday Shankar reportedly spending a fortune leading to financial difficulties afterward

- Kalpana featured over 200 dancers, many trained at Uday Shankar's dance academy in Almora

- It was one of the earliest examples of meta-narrative in Indian cinema with a story-within-a-story structure

- Despite artistic significance, it was a commercial failure, discouraging Uday Shankar from making another feature film

- The film's choreography blended various Indian classical dance forms with modern interpretations

- Kalpana was screened at the 1948 Cannes Film Festival, among the first Indian films to receive international festival recognition

- Uday Shankar's wife Amala Shankar, who played the female lead, was only 16 during filming

- The film's negative was lost for decades before being discovered and restored by the Film Heritage Foundation

- It was India's first major dance film, establishing a template for filming dance in Indian cinema

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception was mixed but appreciative of artistic ambitions. Critics praised Uday Shankar's choreography and visual spectacle, noting groundbreaking approach to integrating dance into narrative cinema. Some found the plot thin and pacing uneven. International critics at Cannes were impressed by its unique aesthetic. Over decades, critical appreciation has grown substantially, with modern scholars recognizing it as seminal work. Contemporary critics praise its innovative structure, choreography, and visual design, considering it ahead of its time. Film historian Shivendra Singh Dungarpur described it as 'a masterpiece of Indian dance cinema that deserves its place among the greatest artistic achievements in world cinema.'

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception in 1948 was tepid, with the film struggling commercially. Indian audiences accustomed to conventional narrative films found the experimental approach challenging. However, it found appreciation among artistic circles and educated urban elite. Many who connected with it were impressed by visual grandeur and Uday Shankar's charisma. Over years, as the film gained cult status, perception evolved significantly. Modern audiences, especially interested in dance and experimental cinema, show greater appreciation. Screenings at retrospectives have been met with enthusiasm. The restoration has introduced it to new audiences who regard it as a hidden gem. Online film communities particularly embrace it, celebrating its contribution to cinematic and dance history.

Awards & Recognition

- Official selection at the 1948 Cannes Film Festival

- Special recognition from the Indian government for Uday Shankar's contribution to arts and cinema

- Special citation from the Film Journalists Association of India for innovative choreography and visual presentation

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Uday Shankar's own stage productions and international dance performances

- Indian classical dance traditions, particularly Kathak and Manipuri

- Western ballet and modern dance forms encountered during international tours

- German expressionist cinema in visual style

- Soviet montage theory in editing dance sequences

- Early Indian filmmakers like Dadasaheb Phalke

- Traditional Indian theater forms in storytelling approach

- Indian classical and folk musical traditions

- Western musical films of 1930s-40s with distinctly different approach

- Indian philosophical traditions on art and imagination

This Film Influenced

- Later Indian dance films integrating classical dance into cinema

- Experimental Indian films of 1950s-60s exploring meta-narrative structures

- Work of Indian dance