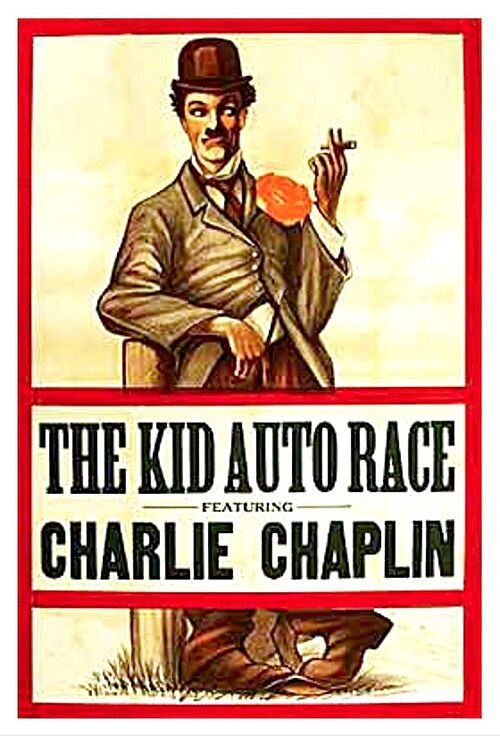

Kid Auto Races at Venice

Plot

In this groundbreaking short comedy, a film crew attempts to document the Junior Vanderbilt Cup auto races held in Venice, California, but their efforts are continually thwarted by an eccentric character who would become known as The Tramp. The bumbling vagrant, played by Charlie Chaplin in his first appearance as this iconic persona, repeatedly wanders into the camera's frame, obstructing shots and disrupting the filming process. Despite the cameraman's increasingly frustrated attempts to shoo him away, the Tramp persists in his interference, mugging for the camera and creating chaos on the sidelines of the actual racing event. The film captures the real atmosphere of the 1914 auto races while simultaneously introducing the world to Chaplin's most enduring character through a series of comedic interruptions and physical gags. The Tramp's stubborn refusal to stay out of the shot culminates in various slapstick scenarios as he interacts with both the film crew and race attendees, establishing the character's signature blend of arrogance and vulnerability.

About the Production

This film was shot on location during the actual Junior Vanderbilt Cup Race held on January 10-11, 1914, making it one of the earliest examples of location shooting with real events as backdrop. The production was essentially improvised, with Chaplin creating his character's behavior spontaneously during filming. Director Henry Lehrman, frustrated by Chaplin's improvisations, attempted to limit his screen time, but Chaplin's natural comedic instincts prevailed. The film was completed in just one day of shooting, typical of Keystone's rapid production schedule. The camera equipment used was a hand-cranked Pathe Professional camera, requiring the cinematographer to manually advance the film while simultaneously framing shots and dealing with Chaplin's interruptions.

Historical Background

The year 1914 represented a transformative period in American cinema, with the film industry rapidly consolidating in Hollywood and moving away from the East Coast production centers. Keystone Studios, under Mack Sennett's leadership, was pioneering the comedy genre with its fast-paced slapstick films featuring the Keystone Kops. The auto racing craze was sweeping America, with events like the Vanderbilt Cup drawing massive crowds and media attention. Venice, California, was a thriving beach resort community known for its amusement pier and canals, making it an ideal backdrop for film production. The film industry was still transitioning from short one-reelers to longer features, and actors were beginning to be recognized as stars rather than anonymous performers. The concept of a recurring character with a distinct personality was relatively new, with most comedy shorts featuring generic characters. The technical limitations of 1914 filmmaking meant cameras were noisy, required hand-cranking, and couldn't record sound, forcing all storytelling to be visual. The film's release date of February 1914 placed it just months before the outbreak of World War I, which would dramatically alter global cinema production and distribution.

Why This Film Matters

'Kid Auto Races at Venice' holds immeasurable cultural significance as the birth of one of cinema's most enduring and influential characters. The Tramp became not just a film character but a global cultural icon, recognized across language barriers and representing the universal struggle of the little guy against authority. This film introduced the template for the recurring film character, paving the way for countless sequels, series, and franchises. The Tramp's distinctive appearance - bowler hat, cane, oversized shoes, and walking stick - became instantly recognizable worldwide and remains one of the most copied costumes in history. The character embodied the contradictions of modern urban life: homeless yet dignified, poor yet proud, disruptive yet sympathetic. This film also established the meta-humor of breaking the fourth wall, with the Tramp acknowledging the camera and filmmaking process itself. The success of this character helped establish Charlie Chaplin as the first true international film star, earning him unprecedented creative control and eventually leading to his own studio. The film's influence extends beyond cinema to art, literature, and popular culture, with the Tramp becoming a symbol of resistance to industrialization and dehumanization. The preservation and continued study of this film provides insight into early 20th-century American culture, including the fascination with automobiles, the growth of leisure activities, and the emerging celebrity culture.

Making Of

The creation of 'Kid Auto Races at Venice' represents a pivotal moment in cinema history, born from the chaotic production environment at Keystone Studios under Mack Sennett. Chaplin, newly arrived from England, had been hired as an actor but was struggling to find his comedic voice. The day of filming, January 10, 1914, began with Chaplin and the crew traveling to Venice to capture footage of the actual auto races. Director Henry Lehrman initially planned a straightforward documentary-style film, but when Chaplin kept wandering into shots, Lehrman's frustration turned to inspiration. The crew decided to incorporate Chaplin's interference into the film's premise. Chaplin spontaneously developed the Tramp's distinctive walk, cane twirling, and arrogant yet pathetic demeanor during filming. Lehrman, accustomed to directing slapstick in a more controlled manner, grew increasingly irritated by Chaplin's improvisational approach. At one point, Lehrman reportedly tried to trip Chaplin or knock him down to get him to stop improvising, but Chaplin incorporated these real frustrations into his performance. The film's meta-narrative of a character disrupting a film shoot was entirely unintentional, arising from the genuine tension between director and star. This tension ironically created the perfect vehicle for introducing a character who would become the most recognized figure in cinema history.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Frank D. Williams represents typical Keystone Studios techniques of 1914, utilizing a hand-cranked Pathe Professional camera that required constant manual operation. The film employs static camera positions for most shots, as camera movement was limited by the heavy equipment of the era. Williams had to simultaneously crank the camera at approximately 16 frames per second while framing shots and dealing with Chaplin's improvised interference. The use of actual outdoor locations provided natural lighting, which was more flattering than the harsh artificial lighting used in studio interiors of the period. The film captures the real atmosphere of the auto races, with genuine spectators and participants in the background, adding authenticity to the comedy. The camera work includes some panning to follow the action, which was relatively advanced for 1914. The interplay between the camera operator (played by Williams himself) and Chaplin creates an early example of meta-cinematography, where the process of filmmaking becomes part of the story. The film's visual style emphasizes the contrast between the serious business of documenting a sporting event and the chaotic comedy created by the Tramp's interruptions.

Innovations

While not technically innovative in the manner of contemporary films experimenting with editing or camera techniques, 'Kid Auto Races at Venice' achieved several significant technical milestones for its time. The film represents an early successful example of location shooting using real events as backdrop, demonstrating the practical advantages of authentic settings over studio recreations. The integration of real documentary footage with staged comedy was relatively uncommon in 1914. The film's meta-narrative approach, acknowledging the filmmaking process itself, was conceptually ahead of its time. The technical challenge of filming during an actual auto race, coordinating the camera work with both the sporting event and Chaplin's improvised performance, required considerable skill. The film's success in creating a complete comedic narrative within the constraints of a one-reel format (approximately 6 minutes) demonstrated the efficiency and effectiveness of Keystone's production methods. The preservation of the film through multiple generations of copies has allowed modern audiences to study early 20th-century filming techniques and comedy performance styles.

Music

As a silent film, 'Kid Auto Races at Venice' had no original soundtrack or recorded dialogue. During initial theatrical release, the film would have been accompanied by live musical performance, typically a pianist or small theater orchestra. The musical accompaniment would have been selected from standard libraries of photoplay music, with selections chosen to match the on-screen action - upbeat, jaunty tunes for the comedy and perhaps racing-themed music for the auto scenes. Some theaters might have used popular songs of the day like 'You're Here and I'm Here' or 'The International Rag' which were popular in 1914. Modern restorations and screenings typically feature newly composed scores or carefully selected period-appropriate music. The film's rhythm and pacing were designed to work with musical accompaniment, with Chaplin's movements timed to allow for musical emphasis. The absence of dialogue meant that all comedy had to be visual, which influenced Chaplin's development of expressive physical comedy that would become his trademark.

Famous Quotes

(Intertitle) The Kid Auto Races at Venice

(Intertitle) The Cameraman tries to film the races

(Intertitle) But a troublesome spectator interferes

(Intertitle) The persistent nuisance refuses to stay out of the picture

Memorable Scenes

- The opening scene where Chaplin first appears as the Tramp, wandering into the camera's frame with his distinctive waddle and immediately establishing the character's signature mannerisms. This moment represents the birth of one of cinema's most iconic figures.

- The sequence where the Tramp repeatedly positions himself directly in front of the camera, forcing the frustrated cameraman to physically move him, only to have Chaplin return moments later with increasingly exaggerated expressions of innocence.

- The climactic scene where the Tramp engages in a physical struggle with the cameraman, using his cane to create chaos while the auto races continue in the background, perfectly encapsulating the film's blend of real event documentation and fictional comedy.

Did You Know?

- This film marks the very first appearance of Charlie Chaplin's iconic Tramp character, though the character would be refined and developed in subsequent films.

- The film was essentially improvised on location during real auto races, with Chaplin creating his character's mannerisms and gags spontaneously.

- Director Henry Lehrman was so annoyed by Chaplin's improvisational style that he nicknamed him 'that English bastard' and tried to sabotage his performance.

- The Tramp's distinctive costume was created by Chaplin himself, reportedly by grabbing mismatched clothing from the communal wardrobe at Keystone Studios.

- The film was shot in just one day, typical of Keystone Studios' rapid production schedule that demanded multiple films per week.

- The actual auto race depicted was the Junior Vanderbilt Cup Race, a real sporting event that attracted thousands of spectators to Venice, California.

- This was only Chaplin's second film appearance in America, having just arrived from England weeks earlier.

- The film's premise of a character interfering with a film crew was meta for its time, predating similar concepts by decades.

- Despite being the Tramp's debut, Chaplin would later claim he created the character by accident when he grabbed random costume pieces.

- The film was considered lost for many years before being rediscovered and preserved by film archives.

- Frank D. Williams, who plays the cameraman, was actually a real cinematographer at Keystone Studios.

- The film's success led immediately to Chaplin starring in 'Mabel's Strange Predicament' the same day, where he further developed the Tramp character.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception in 1914 was limited, as film criticism was still in its infancy and trade publications focused more on business aspects than artistic merit. The Moving Picture World noted the film's novelty in using real race footage but made little mention of Chaplin's performance. Variety, in its brief review, described it as 'a satisfactory comedy short with some amusing interruptions by a new comedian.' Modern critics and film historians recognize the film as a landmark moment in cinema history. The American Film Institute includes it among the most important films of 1914. Film scholar David Robinson has written that 'the birth of the Tramp in this seemingly simple film represents one of the most significant moments in the development of screen comedy.' The British Film Institute's Sight & Sound magazine has noted how the film 'accidentally created cinematic immortality through a series of improvised disruptions.' Modern retrospectives of Chaplin's work consistently cite this film as the essential starting point for understanding his artistic development. The film is now studied in film schools as an example of how character can emerge spontaneously from performance and circumstance.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception in 1914 was enthusiastic but not extraordinary, as the film was one of dozens of comedy shorts released weekly by Keystone. However, audiences immediately responded positively to Chaplin's character, with theater owners reporting increased laughter and requests for more films featuring 'the funny man with the cane.' Within weeks of release, exhibitors were specifically requesting Chaplin films, marking the beginning of his stardom. The film's use of real auto racing footage also appealed to audiences fascinated by the new sport of automobile racing. Audience response grew over time as the Tramp character became more familiar and beloved. By the end of 1914, Chaplin had become one of the most popular performers in motion pictures, largely based on audience reaction to his early films including this one. Modern audiences viewing the film today often express surprise at how fully formed the Tramp character appears in his very first appearance, despite the film's simple premise. The film remains popular in Chaplin retrospectives and silent film festivals, where contemporary audiences still respond to the timeless comedy of the character's interference with authority.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Mack Sennett's Keystone comedy style

- French and British music hall traditions

- Max Linder's comedy films

- Fred Karno's music hall sketches

- Early film chase comedies

This Film Influenced

- Mabel's Strange Predicament (1914)

- The Masquerader (1914)

- The New Janitor (1914)

- A Film Johnnie (1914)

- His New Profession (1914)

- The Champion (1915)

- The Tramp (1915)

- City Lights (1931)

- Modern Times (1936)

- The Great Dictator (1940)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved and available in multiple archives. The original nitrate negative has been lost, but the film survives through 16mm and 35mm copies. The Library of Congress holds a 35mm print in their collection. The film has been digitally restored by several archives including The Museum of Modern Art and the British Film Institute. The restored versions are available on various home media releases and streaming platforms. The preservation quality varies between different versions, with some showing significant nitrate deterioration while others are remarkably clear. The film was included in the 'Chaplin at Keystone' collection released by Flicker Alley, which features comprehensive restorations of Chaplin's early work.