Lambchops

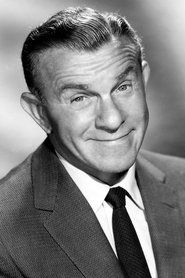

"The Comedy Team That's Making America Laugh!"

Plot

In this early sound short, comedy legends George Burns and Gracie Allen enter an elegant drawing room, seemingly searching for something or someone. After comically looking around the room, George spots the camera and breaks the fourth wall, revealing they were looking for the audience. The duo launches into their signature vaudeville-style patter, with Gracie attempting to convince George that she's intelligent rather than dizzy - a comedic battle of wits where Gracie remains blissfully unaware of her own logical fallacies. Midway through their routine, they perform the song 'Do You Believe Me?' which includes some light hoofing (tap dancing) while continuing their comedic banter. The film concludes with Gracie whispering a story into George's ear, leaving the audience to wonder about the punchline.

Director

Murray RothCast

About the Production

This was one of the earliest film appearances for Burns and Allen, capturing their vaudeville act during the transition to sound cinema. The film was shot using early sound-on-film technology, which required actors to remain relatively stationary near microphones hidden on set. The elegant drawing room set was typical of early sound stages, designed to absorb echo and provide good acoustics for the new recording equipment.

Historical Background

1929 was a pivotal year in cinema history, marking the first full year where sound films dominated the industry following the success of 'The Jazz Singer' in 1927. The transition to sound created both opportunities and challenges for vaudeville performers like Burns and Allen. Many silent film stars struggled with the new medium due to unsuitable voices or lack of stage experience, while vaudeville veterans found their skills suddenly in high demand. The stock market crash of October 1929 occurred just a month after this film's release, beginning the Great Depression that would profoundly affect the entertainment industry. During this time, short subjects became increasingly important to theaters as economical programming that could attract audiences between feature presentations. Comedy shorts like 'Lambchops' provided affordable entertainment during financially difficult times and helped establish the careers of performers who would become major stars in the 1930s.

Why This Film Matters

'Lambchops' represents a crucial moment in the preservation of American vaudeville comedy on film. It captures the classic Burns and Allen routine before it was adapted for radio and television, showing the duo's original stage chemistry and timing. The film is historically significant as an early example of breaking the fourth wall in cinema, a technique that would become more common in later decades. It also demonstrates how early sound cinema served as a bridge between live performance and screen entertainment, helping to preserve performance styles that might otherwise have been lost. The success of this short and others like it helped establish the comedy short as a staple of theater programming throughout the 1930s. Furthermore, it represents the beginning of Burns and Allen's transition from stage performers to multimedia entertainment icons who would influence American comedy for decades.

Making Of

The making of 'Lambchops' occurred during the chaotic transition from silent to sound films in Hollywood. Murray Roth, who had experience directing stage productions, was chosen to helm this short because of his understanding of how to capture live performances on camera. The filming process was challenging due to the primitive sound recording equipment - microphones had to be hidden in props and furniture, limiting the actors' movement. Burns and Allen, accustomed to the freedom of the vaudeville stage, had to adapt their performance style to work within these technical constraints. The duo's natural chemistry made the transition easier, and their timing was so precise that they could deliver their rapid-fire dialogue successfully despite the technical limitations. The film was shot in just one or two days, typical for short subjects of the era, with minimal retakes due to the expense and complexity of early sound recording.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'Lambchops' reflects the technical constraints of early sound filming. The camera remains largely static throughout the short, positioned to capture both performers while staying clear of the hidden microphones. The lighting is typical of the era - bright and even, designed to illuminate the performers clearly for the new medium of sound film. The elegant drawing room set is filmed in a straightforward manner, with medium shots that allow the audience to see both performers' expressions and gestures. The single-camera setup was common for early sound shorts due to the noise and bulk of the recording equipment. Despite these limitations, the cinematography effectively captures the comedy timing and physical comedy of Burns and Allen's performance, ensuring their vaudeville routine translates well to the screen.

Innovations

While 'Lambchops' doesn't feature groundbreaking technical innovations, it represents a successful application of early sound technology to comedy performance. The film demonstrates effective microphone placement and sound recording techniques that allowed for natural-sounding dialogue despite the technical limitations of the era. The synchronization of sound and picture is notably precise for an early talkie, avoiding the lip-sync problems that plagued many early sound films. The successful capture of both dialogue and musical elements in a single take shows the growing sophistication of sound recording by 1929. The film also serves as a technical document of how early sound cinema adapted stage performances for the screen, developing techniques that would influence comedy filming for decades. The preservation of natural comedic timing within the constraints of early sound technology was itself a significant achievement.

Music

The soundtrack for 'Lambchops' consists entirely of diegetic sound - the dialogue and singing of George Burns and Gracie Allen. The film features their performance of 'Do You Believe Me?', a song written specifically for this short that showcases both their singing ability and comedic timing. The sound recording technology of 1929 captures their voices with surprising clarity, though with the characteristic flat quality of early sound-on-film recordings. No musical score or background music accompanies the dialogue, which was typical for early sound shorts that focused on preserving the authenticity of stage performances. The hoofing (tap dancing) sequence includes the sound of their feet on the floor, demonstrating the new technology's ability to capture various sound elements. The entire soundtrack serves to document the duo's vaudeville routine as authentically as possible for the cinema audience.

Famous Quotes

Gracie: 'I'm not dizzy, I'm just a little bit light-headed from being so brilliant.'

George: 'Gracie, you're the only woman I know who can get lost in a revolving door.'

Gracie: 'I told my mother I wanted to be an actress when I grew up. She said, 'You can't do both.''

George: (to the camera) 'We've been looking everywhere for you folks!'

Gracie: 'I'm so smart, I have to wear a hat to keep my brains from falling out.'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where George and Gracie comically search the elegant drawing room before George spots the camera and breaks the fourth wall

- Gracie's attempts to prove her intelligence through increasingly illogical reasoning while George patiently plays straight man

- The musical number 'Do You Believe Me?' where the duo combines singing, dancing, and their signature comedy patter

- The final scene where Gracie whispers a story to George, leaving the audience to imagine the punchline

Did You Know?

- This was George Burns and Gracie Allen's film debut, capturing their vaudeville routine before they became major film and radio stars

- The title 'Lambchops' was a reference to a popular dance of the 1920s, though the dance itself doesn't appear in the film

- The film was one of the first to successfully capture the natural chemistry and timing of a vaudeville comedy team on screen

- Early sound technology required the actors to stand still near hidden microphones, which influenced the static staging of the scene

- The song 'Do You Believe Me?' was written specifically for this short film

- This short was part of Paramount's series of comedy shorts featuring popular vaudeville acts transitioning to sound cinema

- The film's breaking of the fourth wall was innovative for its time, directly addressing the movie audience

- Only one camera was typically used for early sound shorts due to the noise and technical limitations of the equipment

- The preservation of this film is particularly valuable as it captures Burns and Allen's classic routine before they modified it for their later radio and television shows

- The elegant drawing room set was reused for several other Paramount shorts of the era due to budget constraints

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'Lambchops' for successfully translating the Burns and Allen stage act to the new medium of sound film. Variety noted that 'the comedy team's timing survives the transition to talkies with flying colors,' while The Film Daily called it 'a delightful short that captures the essence of popular vaudeville.' Modern critics and film historians view the short as an invaluable document of early American comedy, preserving the duo's classic routine in its original form. The film is often cited in studies of early sound cinema as an example of successful adaptation from stage to screen. Critics particularly appreciate how the short maintains the natural, conversational quality of Burns and Allen's performance despite the technical limitations of early sound recording. The breaking of the fourth wall is now recognized as an innovative technique that predated similar devices in later films.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1929 embraced 'Lambchops' as a familiar and entertaining taste of the vaudeville comedy they loved, now available in the exciting new format of sound pictures. Theater owners reported positive responses to the short, with audiences laughing appreciatively at the duo's familiar routine. The film helped introduce Burns and Allen to a broader audience beyond those who had seen them live on stage, contributing to their growing popularity. Modern audiences viewing the film today often express delight at seeing the early work of the comedy team, finding humor in both the timeless comedy and the charming technical limitations of early sound films. The short has become a favorite among classic film enthusiasts and comedy historians who appreciate its historical value and preservation of classic American comedy.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Vaudeville tradition

- Stage comedy routines

- Minstrel show patter

- Music hall entertainment

This Film Influenced

- The Big Broadcast (1932)

- Many later Burns and Allen films

- Comedy shorts of the 1930s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved and is available through various archives and classic film collections. It has been restored and digitized by several film preservation organizations. The UCLA Film and Television Archive holds a print, and it has been included in DVD collections of early comedy shorts. The preservation quality is generally good considering its age, though some deterioration is visible typical of films from this era. The soundtrack has been cleaned up in modern restorations, improving the audio quality while maintaining the character of early sound recording.